Briefing Report Number 3: Case Studies for Transit Oriented Development (2009)

Reconnecting America for Local Initiatives Support Corp. Phoenix

Case Studies for Transit-Oriented Development offers a useful summary of some of the wide variety of land use and planning techniques that have been used to encourage TOD in communities around the country. These ten tools—many of which have been or can be emulated in New Jersey—are described with case studies. Overall these tools focus on how specified strategies and policies can be linked with TOD and how community benefits can result. The case studies demonstrate the application of the tools in particular places and illustrate the tools’ use and effect.

The tools are:

Livable Communities reviews how the Rosslyn-Ballston Metro Corridor in Arlington, VA accommodated considerable development around five rail stations while promoting the principles of livable communities, including walkability, minimal induced traffic, mixed-use neighborhoods, and increased land values.

Station Area Planning discusses the importance of careful planning for development near stations and the need for a clear time frame, a strategy for implementation, a plan for infrastructure improvement, and clearly identified funding sources. Station area plans that encourage TOD work best when there are significant development opportunities around the transit node. Mission Meridian Village in South Pasadena, California, and Highlands Garden Village near Denver, CO, are highlighted as successful examples.

Community Effort demonstrates how community development corporations (CDCs) can use TOD to revitalize neighborhoods and improve affordable housing near train stations. CDCs can also mobilize the community, including the business community, to support TOD. The well-known Fruitvale BART (Bay Area Rapid Transit) station near Oakland, California, is highlighted as a CDC-led TOD effort.

Right-Sizing Parking discusses that under the right conditions, towns can lower residential parking ratios by 50 percent for TOD projects near high-quality transit service. In turn, changing parking requirements can allow for increases in residential density and developer savings as well as help TOD projects realize community benefits of reduced traffic and better walking and biking conditions.

Shared Parking outlines how spaces shared by more than one user at different times of day can allow communities to more cost-effectively utilize this resource and free up land for higher-value uses. Typically promoted by municipal governments—often through local ordinance—shared parking arrangements are most often implemented by developers and building managers.

Aesthetic Zoning emphasizes the importance of physical form and beauty in the promotion of TOD. One technique, form-based codes, uses architectural and urban form and focuses on the relationships among buildings and between buildings and public spaces to promote the creation of vibrant neighborhoods.

Collaboration, especially public private partnerships (PPP), can be useful for leveraging private investment in TOD and have the added benefit of being more flexible than joint development arrangements. The Pearl District in Portland, Oregon, is held up as one of the best examples of successful PPP. In the early 1990s the city reached agreement with the owner of 40 acres of land wherein the city would build the streetcar past his property and make other improvements if he would up-zone his property from 15 to 125 dwelling units per acre. Today the Pearl District is the city’s densest neighborhood, and at build-out it will be home to 10,000 residents and 21,000 jobs.

Joint Development allows transit agencies to partner with private development partners to ensure that new development is built with uses that support transit ridership and other public goals such as housing affordability and the revitalization of neighborhoods. The report cites the Washington, DC metropolitan area as the nation’s leader in joint development, with some 30 joint development projects.

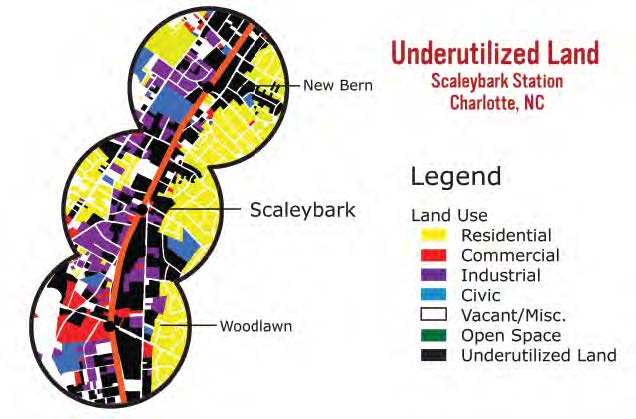

sites that are ready to be redeveloped, making it well suited for

catalytic TOD projects.

Land Assembly can be challenging, so some local governments have used their land assembly powers to amass the land needed to create transit-oriented districts, giving them greater say in determining the kinds of development to be built. Innovative land assembly and financing techniques include making the planning of infrastructure investments and land assembly concurrent as well as using land acquisition or landbanking funds to purchase land around stations or along transit corridors prior to improvements while the land is still affordable. Development fees, flexible state transportation and housing funds, and grants from corporate and family foundations can be a source of capital for land acquisition.

Housing Trust Funds provide stable and steady funding for affordable housing and allow towns to offer a dependable funding source to developers. Targeting these resources to sites near transit is particularly important because TOD can provide increased affordability to households that live near and use transit. These households can save $9,499 a year on transportation compared to those that drive, according to the American Public Transportation Association. The Center for Transit-Oriented Development has shown that households living in walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods near transit spend about 16 percent less on transportation than those that live in conventional suburban development.