Transit-oriented development (TOD) projects have brought thousands of units of housing and square feet of new non-residential space to locations in New Jersey and throughout many parts of the United States. While some projects have worked to address the needs of the entire community, others have rightly drawn criticism as a force for gentrification and displacement. Housing advocates and others have decried these new multifamily projects as being out of reach for lower-income residents. TOD and displacement are not inexorably linked, however. It is important to consider how equity can be advanced in transit-friendly locations. How should the housing—made valuable by its proximity to public transit facilities—be used to benefit the public? How can cities encourage TODs while serving the needs of the most vulnerable in our communities?

Without careful planning, TOD has the potential to perpetuate segregated housing patterns, further entrenching existing physical divisions. But with equity as a guiding principle, transit-oriented developments can improve the quality of life for low-income people across New Jersey. To see how this is possible, we examine equitable transit-oriented development (eTOD) case studies in Asbury Park, Plainfield, and Jersey City as examples of intentional, equitable development in the Garden State.

Asbury Park

In Asbury Park, a city of 16,000 on the North Jersey Coast Line, eTOD is a concerted effort to redevelop and increase the city’s affordable housing stock, especially on the West Side, a historically-disinvested neighborhood close to the commuter rail station. As Asbury Park sees real estate prices rise, the city hopes to ensure current residents are not forgotten.

In the last few years, there has been a dramatic uptick in development on the West Side along Springwood Avenue. In the Springwood Avenue Redevelopment Zone, three affordable housing developments were recently completed: the 64-unit The Renaissance; Boston Way, which replaced an aging public housing block with 104 affordable townhomes; and nonprofit Interfaith Neighbors’ (IFN) 20-unit Parkview AP (Asbury Park) project. More affordable housing developments are in the planning process.

The Springwood Avenue Corridor, the site of a new park and community center, is also close to the Asbury Park Transportation Center. Here, in a neighborhood away from the waterfront, equitable transit-oriented development is happening, in no small part because of the work of Interfaith Neighbors (IFN), a community development organization with a legacy of working for economic revitalization of the area.

Michelle Gladden, Communications Director for IFN, explained the intention of the Parkview AP project, a development of ten townhouses, each with a three-bedroom main unit, and an additional one-bedroom unit below, next to the garage. “If I’m an affordable home buyer, I can live in the one-bedroom and rent out the three-bedroom for market rate. So now my mortgage is completely covered,” Gladden said. “We see this as a game-changer for the community.”

IFN receives funding for projects such as Parkview AP from public and private sources. One funding mechanism is the Neighborhood Revitalization Tax Credit Program (NRTCP), which gives businesses a 100 percent tax credit for donations to nonprofits implementing redevelopment projects. Donors include entities such as New Jersey Natural Gas, Jersey Central Power & Light, as well as banks and corporations.

Speaking from personal experience, Gladden said that IFN’s work building a new park and adjacent community center had certainly “sparked development in that area.” Now, with multiple affordable projects under construction or recently completed, there is visible progress in the economic revitalization of this corridor.

The exceptional need for affordable housing brought on by gentrification helped to spur this change. “We need it all over the city,” Michele Alonso, Director of Planning and Redevelopment at the City of Asbury Park, said. “Last April, we passed wide-sweeping affordable housing ordinances .” Save for the waterfront, Asbury Park now mandates that 20 percent of units in new multifamily developments be reserved for affordable housing.

In planning the redevelopment of a formerly redlined neighborhood, the goal is to avoid reconcentrating poverty. Alonso noted, “The next project in that neighborhood, we anticipate will be mixed-income with 20 percent affordable, so we don’t have along the Springwood corridor a high concentration of 100 percent affordable projects.”

To incentivize interest from developers, Asbury Park uses PILOT agreements, an often-misunderstood funding mechanism. PILOTs or Payment In Lieu of Taxes, offer developers a higher return on investment in the form of lower property taxes. While critics might portray them as handouts, it is important to remember that in many cases, without the PILOT, the project would not be built at all. PILOTS do not necessarily result in lower tax revenues for municipalities. Often, they allow for a recalibration of how revenues are shared, with local governments frequently gaining a larger percentage of funds.

“Every PILOT is an individual negotiation.” Alonso said. “It depends on how much a municipality gives or gives up, and depends on how much they want the development and the benefits that come with the development.” Springwood Avenue, long-dormant, needed new affordable housing. PILOTs enable the construction of new housing in places that would otherwise remain vacant. The negotiations lead to projects, such as the Michaels Organization’s The Renaissance apartments on Springwood Avenue, reserved for people making at or below 60 percent of Area Median Income (AMI).

PILOTs are one tool that can be used to right a historical wrong. In Asbury Park, there is diversified collaboration between the City, the state and federal governments, innovative nonprofits, and private developers. The City is also using regulatory means, such as its affordable housing ordinance to ensure growth in other areas does not drive displacement.

Plainfield

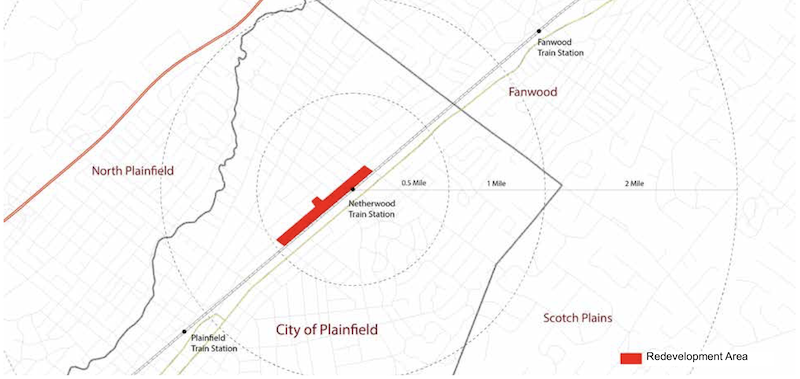

Plainfield, a city of 50,000 in Union County, is using TOD Districts to expand its tax base and channel development funds to local firms and workers. Known as the “Queen City,” Plainfield has two commuter rail stations on the Raritan Valley Line, Plainfield and Netherwood, and NJ TRANSIT’s 59, 113, 819, and 822 bus routes serve the community.

Plainfield scores highly on the CDC’s Social Vulnerability Index relative to surrounding municipalities. In attempting to serve a disproportionate concentration of marginalized populations, the City is looking to TOD. “We want to include every variety of housing stock,” Valerie Jackson, the city’s Director of Economic Development said. “We want the entire community to prosper as Plainfield grows.”

Currently, the City relies predominantly on tax revenue from single-family homes. “I continually explain to the public how we are trying to shift the tax revenue ratio between residential and commercial property owners,” Jackson said.

Projects, like 1000 North Avenue, which is adjacent to the Netherwood Station, help to diversify the tax base, bringing in dollars that are needed for Plainfield to adequately serve all its residents. 1000 North Avenue will add 120 housing units. The project is located in a flood zone, which had previously prohibited construction. The City worked with the Governor’s Office, NJDEP and NJ TRANSIT to develop solutions to overcome this obstacle.

Plainfield is building and renovating its affordable housing stock, too. The Station at Grant Avenue is a workforce housing project that opened in 2021, about a mile from the Plainfield Station. The 59 and 113 buses, with service to Plainfield Station, Newark, and the Port Authority Bus Terminal, are only a few-minutes walk from the complex. The Station is financed in part with funding from the New Jersey Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency (NJHMFA) and a PILOT. The developers are TD Partners and J.G. Petrucci Company.

“Tax abatements are critical for municipalities to incentivize redevelopment,” Jackson said. For both affordable and market-rate projects, Jackson sees communicating the efficacy of PILOTs to community members as an essential part of her work. “We are getting more money under the PILOTs than we would get today if nothing was done,” Jackson said. “It’s very important to reinforce this message with the public.”

Another priority for Plainfield is to connect local laborers with these development projects. The Station at Grant Avenue created 200 local construction jobs, and Jackson’s office works with community organizers to maintain lists of willing workers in Plainfield that are then shared with contractors and developers. They also offer job fairs.

In Plainfield, TOD is about strategically stretching investment to obtain the maximum benefit. Transit-Oriented Development’s promise is one of economic uplift. Plainfield is focused on ensuring that this includes as much of the community as possible.

Jersey City

According to the American Community Survey, Jersey City gained 18,335 people between 2010 and 2017. Not only is the City experiencing surging demand for housing, but more than 40 percent of its households are rent-burdened—that is, 40 percent of households in Jersey City spend more than 30 percent of their income on housing costs according to the United States Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD).

To meet these challenges, Jersey City is using soaring demand to build more affordable housing. On January 1, 2021, the City Council adopted an inclusionary zoning ordinance that allows developers to increase their floor-area ratio (FAR), as long as they include affordable units.

Jersey City’s affordable housing requirement calls for 20 percent of units in new developments to be affordable, though the implementation can be flexible. Only 5 percent of those units must be on-site, the other 15 percent could be included, added on to another project, converted into a payment to the Jersey City Affordable Housing Trust Fund, or translated into a proportionate community benefit, such as a public school, park or transportation improvement. With this new regulatory foundation, the City can harness the surging demand to build in Jersey City and expand much-needed affordable housing stock, as well as improve community amenities.

Bayfront is one project using this affordable housing requirement to transform an entire neighborhood. This massive redevelopment, occurring on Jersey City’s western edge, will be built on a remediated brownfield abutting the Hackensack River. The site’s industrial past as a Honeywell facility kept it apart from the adjacent West Side neighborhood. Bayfront will reconnect the area, adding 100 acres to the urban fabric that will include a new park, school, fire station, the extension of the light rail, and thousands of new units of housing.

According to Annisia Cialone, director of Jersey City’s Department of Housing, Economic Development, and Commerce, the City was able to up the project’s amount of affordable housing by assuming the role of Master Developer (MD), a task usually undertaken by a private partner that collects a fee. Instead, with Jersey City acting as MD, the saved funds can be used to construct additional housing. Instead of 20 percent affordable units, Bayfront will have 35 percent, or nearly 2,500 affordable apartments when the project completes its final phase.

“Bayfront’s affordable housing will transform an underutilized area into an investment in our community by providing access to opportunity,” Cialone said. “It will connect its residents with everything they need to thrive, and will be built at a scale that can have a meaningful impact, particularly to the West Side of our city. Bayfront also allows us to preserve the culture and rich heritage of our city’s longtime residents that might otherwise have been displaced by market rate or luxury development.”

In Jersey City, existing regulations and strategically restructured development arrangements coalesce into a project that will make a real impact on lower income, rent-burdened households, and will ensure they are connected by quality public transit to the rest of the city.

Advancing eTOD in New Jersey

Equitable transit-oriented development begins with a commitment to distribute local growth in a way that elevates the most marginalized in the community. There are no cookie-cutter solutions to implementing eTOD. Planning is a slow, context-driven process, one in which results may take time to be fully realized. But this is reason to start planning now, to build alignment with stakeholders and new partnerships with community groups in order to realize a more equitable future.

eTOD is not easy. It requires creativity, empathy, communication, and commitment to the ideal of a more just, accessible, transit-oriented city. These case studies—regulatory requirements, innovative partnerships, procedural reforms—are mere starting points for municipalities looking to do the same.

The work, difficult as it is, is the ground-level negotiating of the future city, the walkable, vibrant, equitable place that planners dream of providing. Emphasizing eTOD in New Jersey is an opportunity to slowly, and dramatically, transform communities into more equitable, sustainable, and livable versions of themselves. The changes occurring in Asbury Park, Plainfield, and Jersey City are, hopefully, only the beginning.