Transit access, transit-oriented development, and programs like the New Jersey Transit Village Initiative provide an opportunity for New Jersey’s cities and developers to create projects that facilitate transit use, smart growth, and community development, and attract a diverse population of tax-paying residents. However, many cities suffer from a lack of available financing and incentives to offer developers, especially in areas that are experiencing stagnant growth or declining populations. Recent legislation, co-sponsored by New Jersey Senator Cory Booker, the former mayor of Newark, has created major tax benefits for real estate projects designed to facilitate investment in transit-accessible areas, and draw investors into cities and neighborhoods that have struggled to attract development.

Looking to jumpstart investment in neglected areas, a bipartisan partnership between Cory Booker (D-NJ) and Tim Scott (R-SC) reinvigorated the idea of targeted investment with Opportunity Zones and introduced the Investing in Opportunity Act to the Senate in April 2016. The legislation sought to promote investment by reducing the tax burden on the entities underwriting development and businesses in these areas by lessening their reported capital gains. Congress passed the legislation as part of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA).

Under tax law, “capital gains” are any profits made on the sale of an investment, such as a stock, second home, or other equity. When an asset is sold, any recognized capital gains on an asset held for a year or more are taxed at zero percent, 15 percent, or 20 percent, dependent on one’s total annual income. If the asset has been held for less than a year, any gain will be taxed at an individual’s usual tax rate.

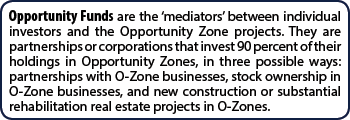

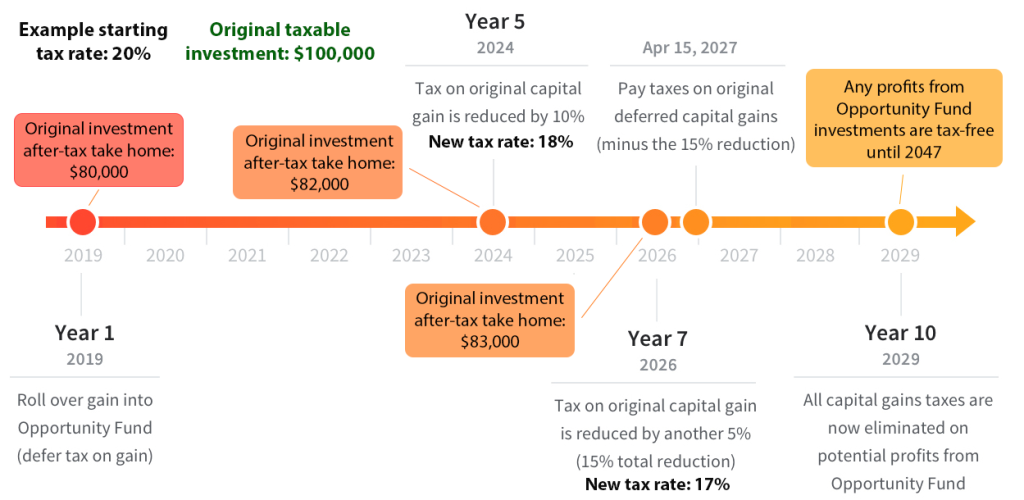

The Opportunity Zone legislation stipulates that, instead of paying tax on capital gains when an asset is sold, any investor has 180 days from the date of sale to reinvest their gains into an Opportunity Fund (see sidebar), with the option to defer recognition of the gains until 2026 at the latest. If the investor keeps their gains unrecognized and held in the Opportunity Fund for five years, they will only be taxed on 90 percent of the original gain after recognizing it. After seven years, only 85 percent of the original recognized gain will be taxed (allowing the individual to take home 15 percent of the initial capital gains tax-free). However, the key benefit to the legislation is that any returns received from the new investment in an Opportunity Fund will be 100 percent tax-free once recognized, if held in the Fund for 10 years. Essentially, an investor is receiving new capital gains through the investment of older capital gains, with tax breaks on both sets of profit.

Any federal taxpaying entity, including individual, businesses, and corporations, is eligible to invest capital gains in an Opportunity Fund. The modified Fundrise timeline below shows a basic summary of the potential cash take-home scenarios for an investor in an Opportunity Fund, based on an original recognized capital gain of $100,000.

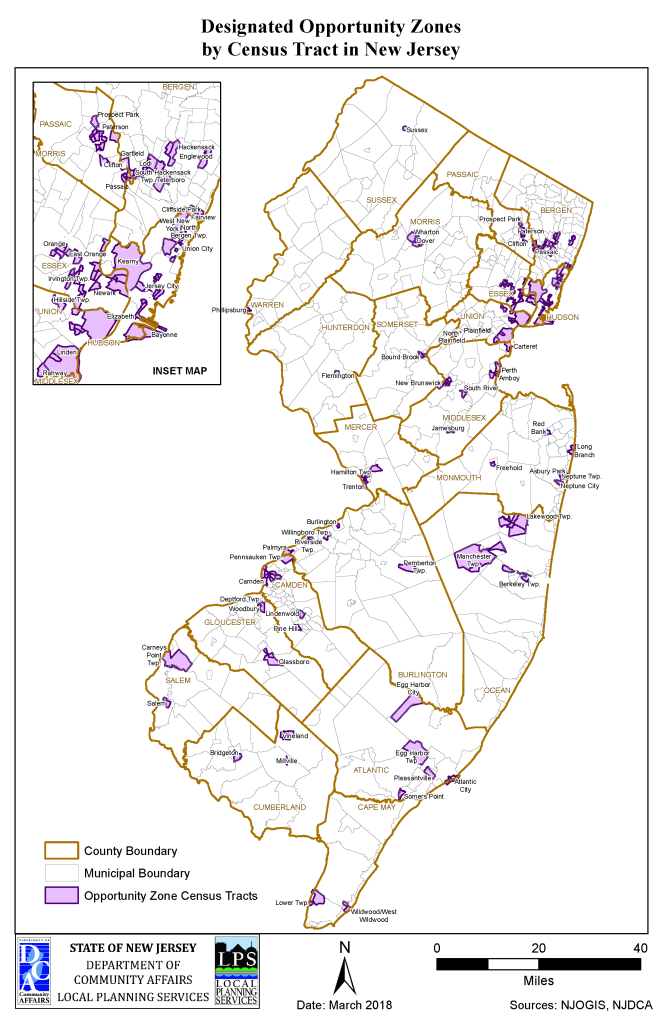

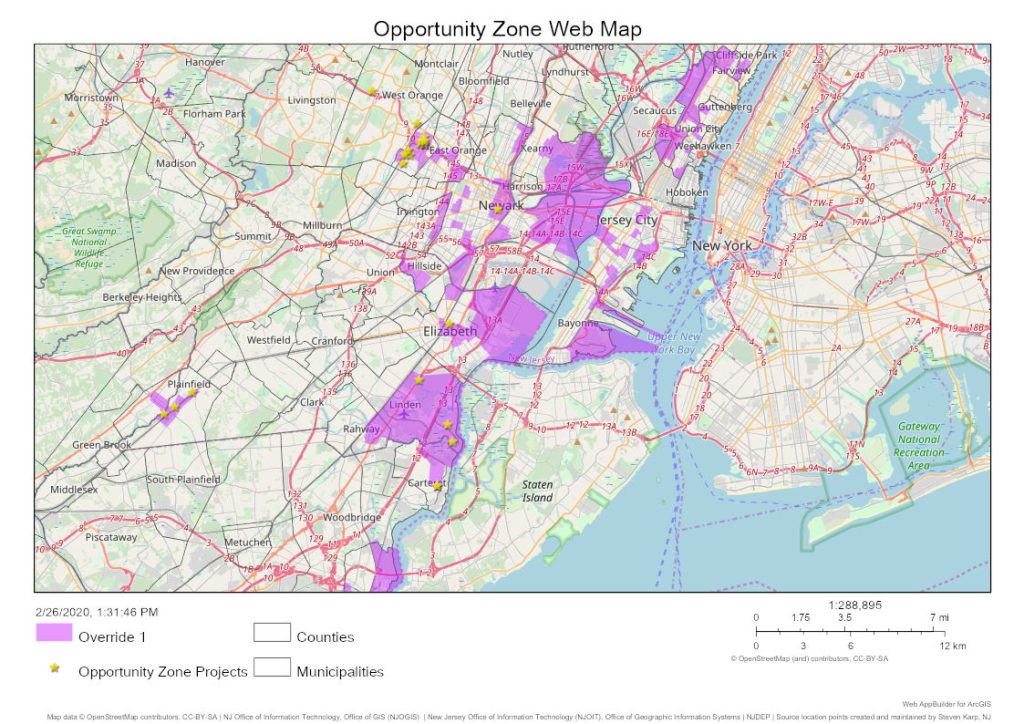

New Jersey Opportunity Zones

The State of New Jersey has 169 census tracts designated as Opportunity Zones, spread across 75 municipalities, or 42 percent of eligible towns. A map of the designated census tracts is shown to the right.

Designation

The Governor’s office led the selection and designation process for New Jersey’s Opportunity Zones. Determination of the most eligible census tracks in the state relied upon a formula that incorporated the Department of Community Affairs Municipal Revitalization Index (MRI), as well as transit access, investment potential, and available state and local financial incentives. The selection process ensured at least one census tract was designated in each county. Additionally, the New Jersey Congressional delegation and municipal mayors provided input on which tracts to designate. Plainfield Director of Economic Development Valerie Jackson says municipal leaders in Plainfield “were intentional” in nominating tracts that would further the city’s “transit-oriented development and Urban Enterprise Zone goals” to the Governor’s office for O-Zone designation. The areas Plainfield nominated were also where the city found it needed “targeted investment.” However, Asbury Park City Manager Michael Capabianco reports that municipal leaders in his city had “no say” in the designation of its two Opportunity Zones.

The New Jersey census tracts were nominated to the US Treasury Department on March 20, 2018, and approved the following month. However, the TCJA legislation did not provide specifics on how Opportunity Funds should operate, thus creating uncertainty around the potential of the program to draw investors into communities. The IRS issued a final set of regulations on December 19, 2019, following two initial draft sets in October 2018 and May 2019, to guide investors and municipalities on the minutiae of the program. These guidelines have allowed municipalities to move forward with their plans for developing their designated Opportunity Zones and alleviated many of the concerns held by investors about the regulations of the program.

Transit Access and Opportunity Zones

According to LOCUS | Smart Growth America, only 9 percent of the nearly 8,500 designated Opportunity Zones in the country contain a transit facility. However, the New Jersey selection process for its Opportunity Zones specifically considered transit access as a factor in designating census tracts. As a result, 60 percent of New Jersey’s 169 Opportunity Zones lie within a half mile of a train station, and 96 percent lie within a quarter mile of a bus station. This allows all but six of New Jersey municipalities with an Opportunity Zone to market their transit access as a benefit for investors.

NJ Transit Villages

Opportunity Zones feature prominently in the development plans of a number of designated NJ Transit Villages. Fifteen of 33 Transit Villages have at least one Opportunity Zone within a half-mile walk of their train station (see sidebar).

Director Jackson reported that, since Opportunity Zone legislation was passed, Plainfield has made efforts to “inform and educate [developers] about the zones,” and hosted an Opportunity Zone Lunch and Learn event for local developers and business owners in April 2019. Plainfield officials are treating Opportunity Zones as “one piece of the capital stack” in their development plans, which also includes PILOTs, NJDEA and Choose NJ financing and funding, LIHTC, and Neighborhood Revitalization Tax Credits

A number of the Borough of Bound Brook’s projects fall within the town’s Opportunity Zones, including its designated Redevelopment Area 2 and arts and entertainment district. Significant portions of planned pedestrian and bicycle riverfront access trails also lie within Bound Brook’s Opportunity Zone census tracts. Bound Brook Mayor Bob Fazen reported that he hopes to “add the Opportunity Zone benefits to [the borough’s] Transit Village and Redevelopment Area plans” after the rules and regulations of the program are finalized, to allow developers to take advantage of additional financing opportunities. Mayor Fazen has prepared an Opportunity Zone Prospectus for developers, highlighting Opportunity360 scores for the borough’s two designated O-Zones, as well as viable existing and new projects eligible for O-Zone tax benefits.

Although many New Jersey municipalities anticipate being able to add Opportunity Zone tax benefits to their developer financing packages, some New Jersey Transit Villages have been unable to plan for O-Zone financing to this point, due to a lack of development in their municipalities. According to City Manager Capabianco, Asbury Park has “no plans” for developing its Opportunity Zones, due to a lack of planned or ongoing projects in these neighborhoods. However, he believed that “sound and reasonable planning documents and standards” will lay the foundation for efficient and equitable development of the town’s Opportunity Zones. Additionally, he stated that if the private sector does decide to invest in Asbury Park’s Opportunity Zones, the available tax benefits can provide “additional funding” to support successful projects.

Other NJ Transit Places

Many other non-Transit Village municipalities with access to transit are including Opportunity Zones in their development plans. Cities such as Passaic and Garfield on the Main/Bergen County Line have been working on long-term redevelopment plans over the past few years. The tax breaks from Opportunity Zone legislation provide another tool to drive their economic growth efforts, especially because their designated zones will encourage more development in walkable urban areas with access to transit and other amenities. The City of Passaic began its redevelopment process by refurbishing the former Sterling Bank Tower at 663 Main Avenue for office space for the Passaic Board of Education and other tenants; the building officially reopened in October 2019. The 663 Main Avenue project spurred more redevelopment, including several housing projects. Joseph Buga, Project Manager for the Passaic Enterprise Zone Development Corporation, stated that Passaic is incorporating two of its four Opportunity Zones into plans for the redesign of Main Avenue in the Central Business District. The plan includes a new $4 million NJ TRANSIT bus terminal which already has federal and county funding in place. Planners believe that the terminal’s location within an O-Zone may provide an additional incentive for investors to develop the area. Buga stated that he believes the city’s O-Zone designations may “stimulate interest in re-using the site[s] [in the CBD] to support both affordable and market-rate residential development,” including around the city’s major public housing project, Speer Village. The O-Zone designations provide “additional capital to projects that need assistance.” One of the O-zones contains former industrial sites available for residential and commercial projects that, if developed, could bring in new residents and additional tax revenue to the municipality.

Projects utilizing Opportunity Zone financing are mapped by the NJ Department of Community Affairs on their Asset Map.

Investment Potential

Many New Jersey municipalities, especially those with transit assets, were already planning and undergoing development work before the legislation passed. The legislation and guidelines create additional profit options for developers of these areas, and provide an incentive for developers to consider projects in other underserved areas. Supplementing the original legislation that appeared to cater primarily to real estate investments, the most recent set of guidelines provides specifics on how businesses must operate to take advantage of the Opportunity Zone benefits. This new information has created an opening for municipalities to fully flesh out their development plan financing to include bringing in new businesses, on top of funding real estate projects.

Since the legislation passed, many reports and analyses have been published to guide investors in deciding which of the 8,700 designated Opportunity Zones to fund. LOCUS, in conjunction with Smart Growth America, published a report in December 2018 to encourage investment in areas that would provide both environmental and community benefits. The report rates Opportunity Zones across the United States based on two factors:

- Smart Growth Potential – based on walkability, job density, housing diversity, and distance to the nearest top 100 central business districts.

- Social Equity + Social Vulnerability – based on transit accessibility, housing and transportation affordability, diversity of housing tenure, and a Social Vulnerability Index.

New Jersey had three Opportunity Zones in the top 50 LOCUS rankings for Smart Growth Potential – Downtown Newark, Journal Square, and North Ironbound (Newark). Additionally, Downtown Newark ranked fourth for a combined highest Smart Growth potential and highest Social Equity and Vulnerability score. This high ranking, according to the report, indicates that Downtown Newark is a good place for smart, sustainable investments that carry a minimized risk of displacement of resident populations. The City of Newark can utilize this high score from LOCUS, as well as its combined NJ TRANSIT commuter rail, bus, and light rail, and PATH access, to draw investment for projects such as the Gateway Center or the renovation of Newark Symphony Hall.

Even without published rankings for new places to invest, many NJ municipalities are utilizing the Opportunity Zone legislation as an additional financing option for ongoing projects in their towns. Developments in the state are supported on a local level by existing financing methods such as PILOTs, and on a state level by various financing and incentive programs, including those offered by the New Jersey Economic Development Authority. The City of Passaic plans to use a number of policies and incentives in conjunction with Opportunity Zones to redevelop its designated tracts, including NJ Garden State Growth Zone and Urban Enterprise Zone status, PILOTs, Payments in Lieu of Parking (PILOP), and its local outdoor dining and retail sales ordinances. The Opportunity Zone Challenge Program, administered by the NJ EDA, is intended to provide resources to communities in New Jersey that have Opportunity Zone designations, but lack the long-term investments and local government funding to effectively utilize their O-Zone status. In November 2019, NJEDA announced the five locales that will each receive $100,000 grants in the first round of funding: Cumberland County, Hackensack, Flemington Borough, Paterson, and Jersey City.

The Future of Opportunity Zones

Potential Challenges

There are several deadlines in Opportunity Zone legislation that must be considered as cities work to accumulate investment in their zones.

| Date | Event | Implication |

| December 31, 2026 | Latest date to defer tax on original capital gains investment. | Original capital gains investment must be withdrawn from Opportunity Fund to report to IRS and pay taxes owed. |

| December 31, 2028 | Opportunity Zone designation by US Treasury Department expires. | O-Zones no longer eligible for new investments under TCJA law. |

| December 31, 2047 | Latest date at which an investor can exclude any new gains from tax burden. | In order to take new capital gains home tax-free, investors must withdraw from O-Zones to report gains to IRS. |

These deadlines have various implications for the fate of Opportunity Zones; primarily, in 2026 and the years leading up to 2047, areas may experience a rapid sell-off of properties and investments so that investors can divest from Opportunity Funds and capitalize on their tax benefits. Cities must actively work in the years leading up to these deadlines to ensure their Opportunity Zones do not suffer if or when the new businesses, residences, and other developments are sold or lose value as investors pull out of the market.

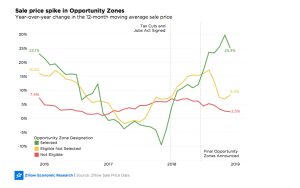

Gentrification and displacement in up-and-coming areas bear consideration when planning within Opportunity Zones. Real estate marketplace Zillow reports that home sale prices in designated Opportunity Zones increased by 20 percent over the course of 2018, the year after TCJA was passed. Additionally, the LOCUS report states “the authorizing legislation and proposed regulations for Opportunity Zones do not contain any guardrails or social impact requirements that ensure that investments neither crowdsource displacement or accelerate climate change or the negative socioeconomic impacts by repeating the land use and development mistakes of the 20th century.” If home sale prices in Opportunity Zones continue to rise rapidly, it is possible that many current residents of these areas will be unable to endure the higher rents or property taxes that accompany increased property values.

The LOCUS report’s Social Equity and Vulnerability score serves to alleviate the potential displacement issue by indicating which census tracts are least likely to experience negative effects if they gain investment, such as the zone in downtown Newark. Additionally, community development organizations like the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC) are lobbying the Treasury Department to issue certification guidelines that would minimize the displacement effects of any projects funded through Opportunity Zone money. These efforts, combined with tools such as the LOCUS report, smart investment, and local government policy to support community needs and counter displacement, can be utilized to encourage investment and development in a region, while minimizing the potential for gentrification and displacement.

Potential for Success

The Opportunity Zone law was created to incentivize private entities to invest in areas desperately in need of capital by reducing and eliminating their tax burden. Without the law, much of the necessary capital may have remained sitting in stock options or real estate investments in areas that benefit only minimally from the investment.

Opportunity Zones were specifically selected because development in these neighborhoods has the potential to elevate and improve the lives of each zone’s residents and revitalize underserved communities. Many New Jersey municipalities, as well as cities across the country, are considering Opportunity Zone tax benefits as a financing option to spur new investments and continue much needed development projects.

Our thanks to Valerie Jackson, Director of Economic Development for the City of Plainfield, Michael Capabianco, City Manager for the City of Asbury Park, Mayor Bob Fazen of Bound Brook, and Joseph Buga, Project Manager for the Passaic Enterprise Zone Development Corporation for offering their insights.