As transit-oriented development (TOD) gains momentum across the country, accommodating people who want to live, work, and play near transit, a new movement – Complete Streets – has emerged to bolster TOD. The focus of the Complete Streets movement is, as the name implies, to provide communities with streets that are safe and accessible for users of all ages, abilities and multiple modes – in other words “complete.” The Complete Streets movement shares with TOD over-arching goals to build livable, vibrant, healthy communities that are accessible to pedestrians, cyclists, motorists, and public transit users.

The National Complete Streets Coalition promotes the adoption of “complete streets” policies and planning around the country and provides resources for those interested in implementing such policies in their community. The coalition looks to change the focus of transportation planning at the local, state, and federal levels by shifting planning towards measures that increase access for all users, not just motorists:

By adopting a Complete Streets policy, communities direct their transportation planners and engineers to routinely design and operate the entire right of way to enable safe access for all users, regardless of age, ability, or mode of transportation. This means that every transportation project will make the street network better and safer for drivers, transit users, pedestrians, and bicyclists – making your town a better place to live.

National Complete Streets Coalition 2011

The Complete Streets movement and its focus on accessibility and good design and avoidance of over reliance on automobiles, make it a strong partner for transit-oriented development. The focus of TOD is to create and promote vibrant neighborhoods near public transit, often in centers of medium- to high-density development that mix retail, employment centers, public space, and a variety of housing options for economically and socially diverse populations. These goals can be aided by complete streets’ focus on pedestrian and bicyclist access.

Complete streets around and within TOD can provide complete access networks for cyclists and pedestrians to transit centers. This will help address the issue of the “last-mile problem” for public transit users, where commuters are less likely to take transit if the trip between home and transit is not accessible or takes too long by using other public transit, bicycling, walking, or driving.

The transit center, connected to TOD via complete streets, becomes an important center of community interaction. Complete streets make people feel comfortable using alternative forms of transportation to transit centers, alleviating issues of parking and congestion around them. Another positive interaction between complete streets and transit centers is that complete streets can also help create TOD as an important destination for the surrounding community.

Because complete streets support all forms of transportation, more people are encouraged to walk, bike, or use transit for their short-distance trips to school, shopping, or other activities. About half of all trips in the US are short trips of three miles or less. Encouraging more people to walk, bike, or take transit, complete streets helps to decrease congestion and improve safety for motorists and non-motorists alike. Complete streets also offer greater autonomy for travelers who don’t have access to or who choose not to own cars, including children, the elderly, and the disabled. It can help create communities where residents can live well without owning cars – such as folks living in TODs.

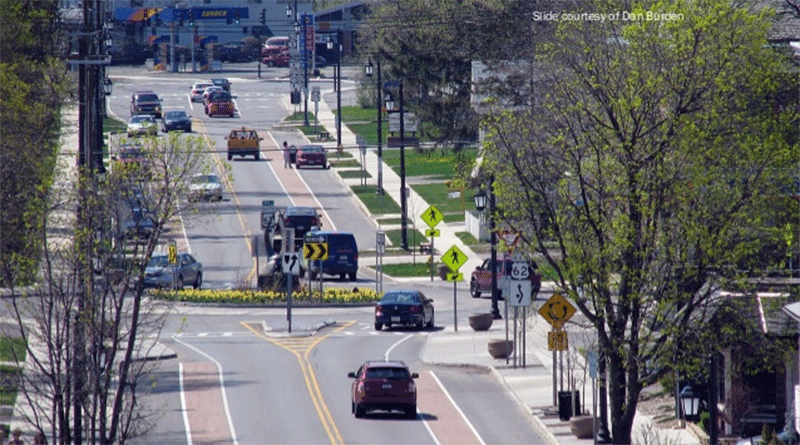

Different complete street standards apply to rural areas, suburban areas, residential neighborhoods, arterial roads, and commercial corridors and can take additional care when transit is part of the mix. Some measures communities and transportation planners can take to improve conditions for pedestrians and those taking transit include widening sidewalks, installing curb ramps for wheelchair access following ADA standards, slowing down traffic, and making all users more visible through the addition of bicycle lanes or off-street bicycle paths, curb bulb-outs, medians, speed humps, and highly visible crosswalks. Other measures, such as improvements to lighting and the addition of secure bicycle parking at transit centers allow users to feel personally safe when walking or cycling early in the day or in the evenings. Many of these measures are low-cost.

Complete streets are part of what makes transit-friendly communities healthy, active places to live. This is especially important given the rising obesity rate in the US, especially among children. Living in a walkable community – one that has streets that are designed for all users – helps to prevent obesity. A 2004 study looking at Atlanta residents found that “people who live in the most walkable neighborhoods were 35% less likely to be obese than those living in the least walkable areas” of the city.

Walkability and transit access are an even more effective combination for livability as research from New York City recently demonstrated. The New York Department of Health survey found that NYC residents who travel by transit to work get nearly an hour’s worth of physical activity each day, only a small portion of which is from recreation. Most New Yorkers, living in a transit-rich location, get their daily exercise by walking to the bus stop or subway station or by running errands.

Both TOD and complete streets can also help residents financially. Many American households spend more on transportation than on food, while low-income households spend almost a third of their income on transportation. By offering low-cost transportation alternatives that are safe and accessible, complete streets can help lower the overall cost of transportation for families and individuals.

Along with fostering healthy and affordable communities, complete streets can also add to a healthy economy. By expanding sidewalks and designing them with street furniture, trees and other landscaping, community members are encouraged to spend more time interacting with their surroundings. This is important along commercial corridors where pedestrians will spend more time walking along first-floor shops, restaurants, and businesses. A study by Todd Litman and the Victoria Transport Policy Institute in 2010 found that investments improving walking, bicycling, and public transportation increase retail sales by 30% and land value by 70% to 300%. These design improvements are especially important for TOD locations as having well-designed and inviting streets are essential to their success.

The last five years have been an especially fruitful time for the complete streets movement as recognition of all users has grown and policies have been adopted by municipalities, counties, and states throughout the US. New Jersey has been at the forefront of this movement. The NJ Department of Transportation (NJDOT) adopted its complete streets policy in 2009, which is designed to guide the planning, design, construction, maintenance, and operation of new and retrofitted transportation facilities within public rights of way that are federally or state funded, including projects processed or administered through the NJDOT’s Capital Program.

Several NJ counties and municipalities, which make decisions for a majority of roadways in the state, have also begun to implement complete streets resolutions. As of June 2011, there are thirteen municipalities and one county (Monmouth County) that have passed complete streets resolutions. See New Jersey Bicycle and Pedestrian Resource Center for more information. Several of these communities have actively been pursuing TOD agenda as well. Four of these municipalities – Montclair, Netcong, Bloomfield, and Jersey City – are also designated NJ Transit Villages, a smart growth initiative supported by NJDOT, NJ TRANSIT, and other state agencies.

In New York, Governor Cuomo signed Complete Streets legislation on August 15, 2011. The new law requires that the NY Department of Transportation consider complete streets design principles on its projects and on all local and county projects that receive federal and state funding and that are subject to its oversight.

Federal support for complete streets has also been growing. On May 5th, 2011, the Safe and Complete Streets Act of 2011 was submitted to the House of Representatives Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure. The bill, introduced by Representatives Matsui (CA-5) and LaTourette (OH-14), sets as a goal “to ensure the safety of all users of the transportation system, including pedestrians, bicyclists, transit users, children, older individuals, and individuals with disabilities, as they travel on and across federally funded streets and highways” (H. R. 1780). A companion bill was introduced to the Senate on May 24th 2011 by Senator Harkin (IA) (S. 1056).

For further resources and information on how to implement complete streets policy in your community, please visit these sites:

- National Policy and Legal Analysis Network’s (NPLAN) Complete Streets Model Laws and Resolutions

- National Complete Streets Coalition

- The New Jersey Bicycle and Pedestrian Resource Center

- The APA and National Complete Streets Coalition’s Complete Streets: Best Policy and Implementation Practices