Eminent domain—the taking of private property for public use and a tool often used in transit-oriented development—has become one of the most fiercely debated planning and policy topics in recent years, due to the U.S. Supreme Court’s controversial decision involving a redevelopment case in New London, CT.

Belmar, Bloomfield, Collingswood, Long Branch, Newark and New Brunswick have all recently acquired properties surrounding their transit stations, and some have been sued by local businesses or homeowners claiming municipal officials overstepped their bounds. The Supreme Court in its New London decision invited states to adopt laws limiting the power of municipalities to seize property. New Jersey lawmakers have begun a rigorous examination of the legal framework for the exercise of eminent domain and hope to act later this year.

Advocates argue that the exercise of eminent domain plays a crucial role in the revitalization of communities. They claim that without the ability of municipalities to seize dilapidated or derelict properties, cities will be left with numerous incongruous parcels in need of redevelopment. Organizations such as the Brookings Institution and the American Planning Association (APA) recognize that major commercial and residential developers are attracted to larger projects for their substantial return, and that such developments additionally have the power to catalyze broader revitalization efforts. These groups are in agreement with the Supreme Court decision which found that governments can appropriate privately owned properties (including homes) provided their owners are paid “just compensation” and the reclamation serves a “public good” by spurring economic development and increasing the municipality’s economic well-being.

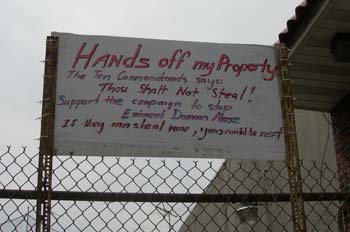

Opponents include citizen and property rights advocates who argue that the New London decision has given cities too much subjective power to deem whether or not certain properties are worthy of seizure. Critics also fear the decision went too far, as the definition of “just compensation” fails to account for such unquantifiable factors as social ties to an area, local client bases, or the potential versus the current market value of a business or residence.

This issue can have major bearing on the implementation of transit-oriented development (TOD), as municipalities must often resort to acquiring properties surrounding transit stations in order to aid the development process. Train stations often are surrounded by a great deal of underutilized land that is needed to facilitate larger and, at times, higher impact development projects.