To combat urban sprawl and its negative externalities, planning researchers and professionals have increasingly turned to infill development as a solution. Infill development typically refers to new development on vacant, abandoned, or underutilized properties within established urban areas. However, the definition varies across municipalities, research studies, and individual interpretations. For example, debates persist on whether infill should be limited to vacant lots or extended to include vacant or underutilized buildings (Listokin 2007).

Proponents argue that infill can increase urban density, revitalize downtown areas, reduce vehicle miles traveled (VMT), and make better use of existing infrastructure (McConnell and Wiley 2010). Critics, however, point to the political and economic challenges of infill development: higher land values, potential teardown or environmental cleanup expenses, increased construction costs, and community opposition. The obstacles can limit feasibility outside of the most active real estate markets (Gabbe et al. 2021).

This paper reviews the literature on the economic, financial, political, and environmental dimensions of infill development. The analysis highlights key areas of debate, beginning with one of the most contested issues: property values.

Property Values

A central concern in community debate over infill development is its impact on local property values. This issue often drives neighborhood opposition, alongside worries about traffic congestion and lost open space (Evans 2004). Yet research on the property value effects of infill is mixed.

A 2022 study by Nygaard, Galster, and Glackin examined property prices near infill projects in Melbourne, Australia, analyzing changes within five concentric 100-meter rings around project sites. The study found that small-scale infill projects (1–4 units) were linked to modest increases in nearby property values, likely reflecting the positive amenity of cleaning up and reactivating vacant lots. Mid-sized projects (5–49 units) had no measurable effect on single-family home prices, though apartment prices experienced slight declines consistent with localized supply effects. Large-scale developments (50+ units) produced initial decreases in nearby single-family home values, but these effects dissipated within five to seven years. Large projects were also associated with lower nearby rents, suggesting a supply-driven effect (Nygaard, Galster & Glackin 2022).

Other studies report different outcomes. An MIT study of suburban Boston (Pollakowski et al. 2005) examined mixed-income, multi-family infill housing built between 1983 and 2003. These developments—often denser than surrounding single-family neighborhoods and including 25 percent affordable units—had no discernible effect on nearby home values relative to broader market trends. Similarly, Wiley (2009) assessed townhouse infill projects in predominantly single-family neighborhoods over multiple years. Across model specifications, the research identified small but consistent negative effects on property values, typically less than a 0.5 percent decline.

Geographic context also shapes results. A U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) study used a hedonic pricing model to evaluate property values near remediated brownfield sites, drawing on national EPA brownfield data from 2005 to 2013. The analysis found increases between 5.1 percent and 12.8 percent in surrounding areas (Haninger, Ma & Timmins 2012).

A study by Brunes et al. (2020) analyzed multi-family infill development in Stockholm, Sweden, between 2005 and 2013 using quantile regression models. The results indicated a small but statistically significant positive spillover effect—approximately a 1 percent increase in property values—but only in low-income neighborhoods. No significant impact was observed in higher-income areas

Taken together, the literature shows that the effects of infill development on property values are highly context-dependent: while small-scale projects often generate modest increases, large-scale or denser developments may produce temporary declines, neutral effects, or benefits that vary with neighborhood income levels and broader market conditions.

Construction and Infrastructure Costs

While research on infill development’s impact on nearby property values is mixed—typically showing minimal, temporary increases or decreases—the effects on municipal and construction costs are more concrete and better documented.

A comparative study by Hamilton and Kellett (2017) analyzed infrastructure costs for greenfield development on the urban fringe versus infill development within the urban core across the Adelaide metropolitan area in Australia. Despite challenges posed by inconsistent record-keeping and accounting practices, the researchers found that infrastructure costs for infill development were approximately one-third of those for greenfield development. These savings reflected the ability of infill projects to connect to existing networks for water, sewage, electrical utilities, roads, parks, and schools, rather than requiring new investment.

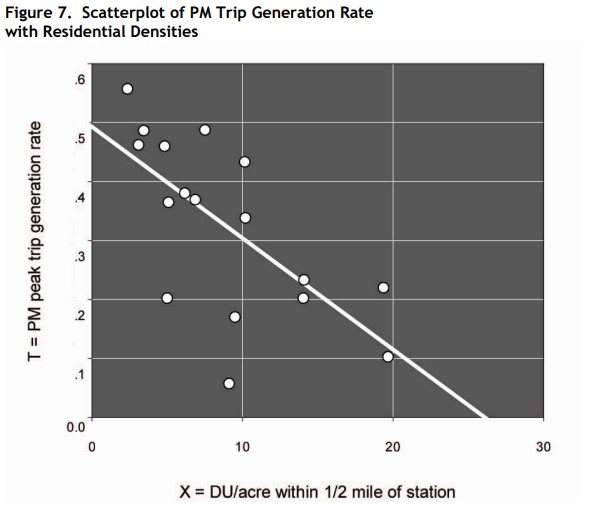

Infill also contributes to a stronger municipal tax base by converting underutilized or vacant parcels into taxable properties (Carswell 2017). Additional savings may be realized in infill projects near transit stations due to reduced parking needs. One study found that residents of transit-oriented development (TOD) infill projects used private vehicles at nearly half the rate predicted by the Institute of Traffic Engineers’ standards. For a mid-rise development, reducing parking by 50 percent could lower total construction costs by nearly 20 percent (Arrington & Cervero 2008).

While municipalities often benefit from infill, developers and financiers can encounter higher costs and greater risks. Projects can require complex due diligence, including site assembly, environmental remediation, and demolition. Regulatory hurdles are also common, particularly in built-up neighborhoods where zoning restrictions, permitting delays, and community opposition can slow approvals. In some cases, infill may also necessitate the displacement of existing residents, adding social and financial complexity.

A study of community development corporations (CDC) highlighted how financial viability depends heavily on the local housing market. In hot markets, CDCs faced high acquisition costs, intense competition, and strong community resistance—especially for affordable housing. To overcome these challenges, CDCs often partnered with municipalities to reduce costs and expedite approvals. In weaker markets with excess vacant land, CDCs instead pursued projects in disinvested neighborhoods, aiming to stimulate reinvestment and neighborhood revitalization (Felt 2007).

For private developers, infill is most financially viable in strong, high-demand markets. A 2024 study by Jun et al. used deep learning and multilevel modeling to identify drivers of residential infill in Los Angeles. The researchers found that residential infill was more likely on larger lots with good transit access, and in higher-income, majority-white neighborhoods.

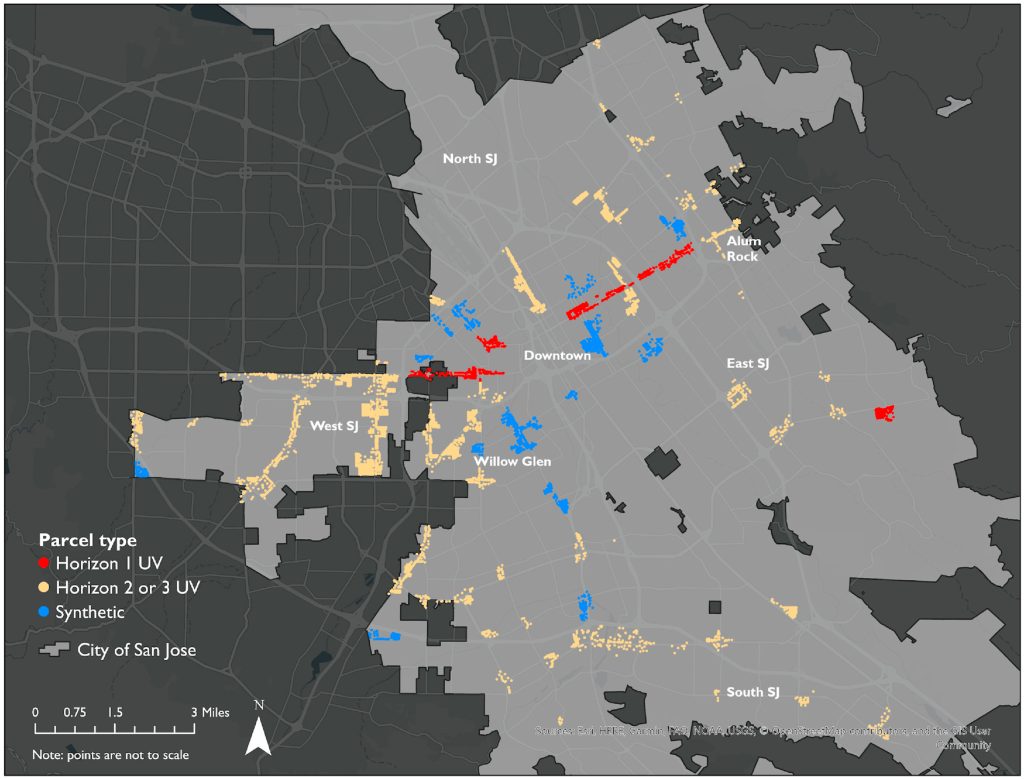

Policy reforms alone have not always overcome these market barriers. For example, in 2011, San Jose launched an “Urban Village” initiative to encourage high-density, mixed-use infill development by upzoning 68 areas. Despite this effort, the designated urban villages experienced no significant increase in development activity relative to surrounding areas, largely due to high land and construction costs and lengthy approval processes (Gabbe et al. 2021).

Construction costs themselves remain a central challenge across the United States. On average, construction accounts for 64.4 percent of a home’s final sales price (Lynch 2025). Between 2019 and 2024, costs rose by 44.5 percent, driven by rising commodity prices and persistent labor shortages. Even in areas with substantial infill investment, these cost pressures have fueled rising housing prices. In Jersey City, for example, average rents increased by 25.5 percent between 2020 and 2025, despite significant new infill construction (Apartment List 2025).

Overall, the literature suggests that while infill development can reduce public infrastructure costs and expand municipal tax bases, private-sector feasibility is constrained by high acquisition and construction costs, regulatory hurdles, and market-specific dynamics. These contrasting incentives help explain why infill tends to cluster in strong markets despite widespread policy efforts to encourage it.

Transit and Environment

Infill development is often supported for its positive externalities, particularly its role in reducing sprawl and expanding transit use. Research has shown that clustering residents closer to employment centers through residential infill reduces VMT and increases transit ridership in areas with accessible rail or bus service (Salon et al. 2012). Locating infill near transit is especially effective: a California Department of Transportation study (2016) found that areas within a half-mile of transit stations experience far higher rates of infill than other areas, with station activity strongly influencing outcomes. Stations with higher ridership and more frequent service attract more infill than those with limited service.

Resident opposition to infill due to increased congestion contributes to why infill is most common near transit stations. In a study of CDCs, professionals with experience constructing infill reported that congestion and property values were the two most common complaints existing residents voiced (Felt 2007).

Most research finds that infill reduces VMT on a per-capita basis. Transit-oriented development (TOD) residents, for example, drive at nearly half the rate predicted by the Institute of Traffic Engineers manual (Arrington and Cervero 2008). Modeling of infill in the Bay Area suggests that such developments can reduce household VMT by up to 27 percent (Ratto 2023). A case study of a large-scale TOD in Atlanta showed new residents drove significantly less than comparable residents elsewhere in the region, although existing residents’ travel patterns remained largely unchanged (Merlin 2018).

These reductions are even greater when infill is paired with mixed-use development. A nationwide study using Gaussian multivariate regression across 710 mixed-use projects found that such developments generated about one-third fewer VMT than conventional projects and produced significantly lower CO₂ emissions (Tuffour et al. 2025).

While infill reduces VMT, it can still increase local congestion. However, the broader environmental benefits are significant. In urban counties, VMT correlates strongly with air pollution, and reductions in vehicle use yield disproportionately large improvements compared to rural areas (Ngo et al. 2024). Higher VMT is also linked to elevated health risks from pollution exposure (Zhang and Batterman 2013).

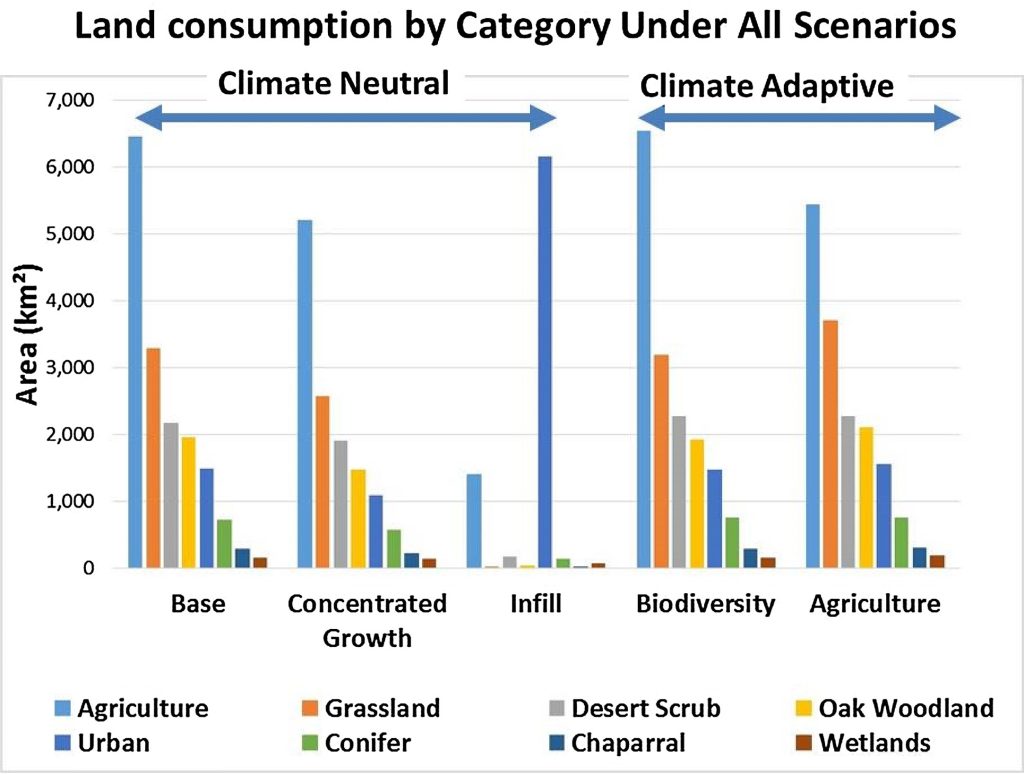

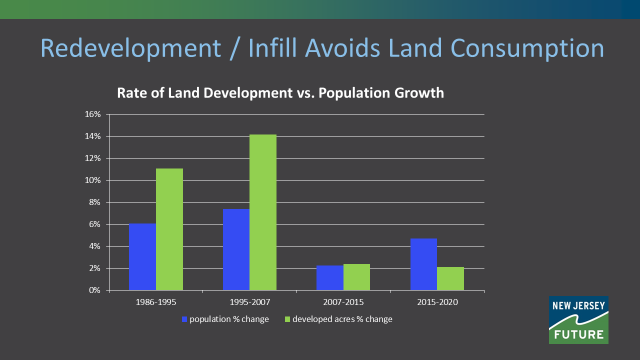

In addition to lowering VMT, infill reduces land consumption. Modeling by California researchers of three climate-neutral urban growth scenarios projected through 2050 found that infill preserved 46–57 percent more land than business-as-usual or compact-growth alternatives (Thorne et al. 2017). Reduced land use, in turn, supports biodiversity, preserves agricultural land, and lowers water demand (Newbold et al. 2015; Lambin and Meyfroidt 2011; Grimm et al. 2008).

However, infill poses environmental challenges as well. One major critique is its contribution to flooding risk by increasing impervious surface coverage. A study of Belgian cities found that unrestricted infill in flood-prone zones would significantly heighten exposure to flood damage (Mustafa et al. 2018). Similarly, research in Denver showed that a 1 percent increase in impervious area from infill led to a 1.28 percent increase in runoff volume (Hogue et al. 2017). Moreover, relying on underutilized or vacant parcels to manage flooding risk is not a durable strategy; without complementary investments in permeable surfaces, green infrastructure, and stricter controls in flood-prone areas, such an approach can actually increase vulnerability over time.

The research suggests that infill delivers meaningful environmental gains—lower VMT, reduced emissions, and preserved land—especially when transit access and mixed uses are integrated into development. Yet its long-term success depends on anticipating localized drawbacks, such as congestion and flooding, and addressing them with design and policy rather than assuming the benefits alone will carry the day.

Policy Implications

Infill development offers municipalities a range of benefits. It reduces infrastructure expenditures, expands the tax base, lowers pollution and land consumption, and helps revitalize downtowns. Evidence also suggests that it produces little to no negative impact on property values, while infill residents drive less—countering two of the most common criticisms raised by local opposition. Although infill is not a primary tool for generating affordable housing, these other advantages make it highly attractive to local officials.

Yet, as the San Jose study (2021) illustrates, simply upzoning does not automatically lead to new infill construction. Policies must also address practical barriers, such as lengthy community oversight processes and rigid zoning standards that limit development on irregular parcels.

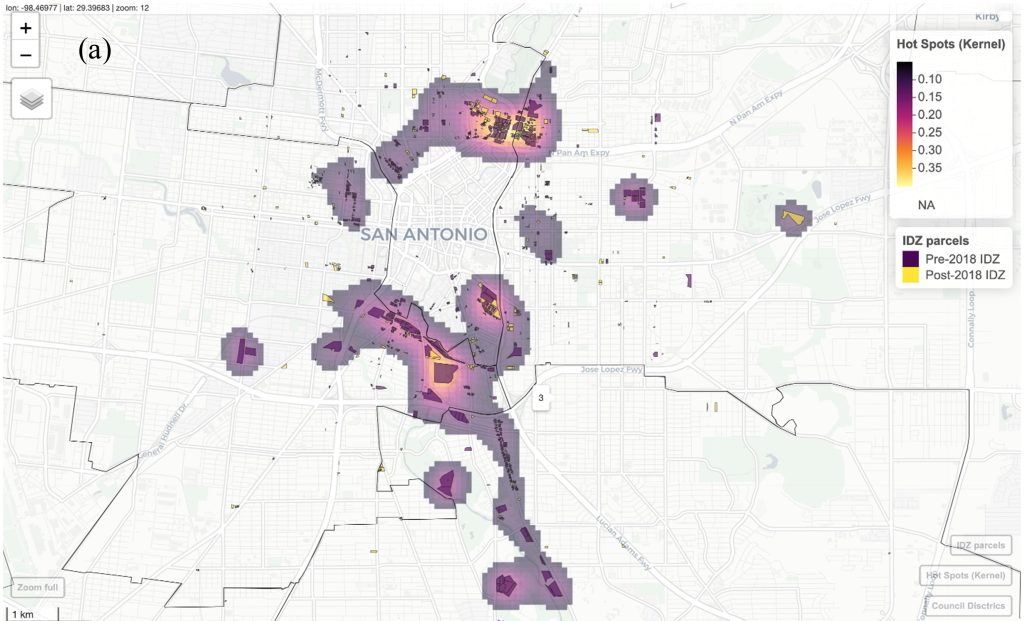

San Antonio provides a useful case study. In 2001, the City adopted a unified development code that created an Infill Development Zone (IDZ) to counteract its “donut-shaped” growth pattern. The IDZ was amended in 2018 to address stakeholder concerns while maintaining its goal of streamlining the approval process. Property owners can apply for IDZ rezoning, which takes 60 days, with a zoning commission hearing followed by a City Council decision. If approved, developers can create customized zoning with flexible setbacks, heights, land-use mixes, and open space requirements. Parcels in the IDZ are exempt from stormwater requirements, utility upgrades, and traffic impact studies, though approvals often require compromise with council members on sustainable design features.

An evaluation of IDZ rezonings between 2017 and 2023 found that most applications were for middle housing defined as up to low-rise apartments (26.8%) or large-scale mixed-use projects defined as at or above 40 units per acre (23.7%) (Quattro and Ochoa 2025). The tool proved particularly useful for irregularly shaped parcels that could not meet traditional code standards and for older low-income neighborhoods—many of which developed as streetcar suburbs but rendered nonconforming by auto-oriented zoning. IDZ rezonings were distributed citywide, but most concentrated in low-income transit corridors. The study concluded that while the IDZ effectively facilitated infill, more research is needed to assess the long-term implications of stormwater and traffic waivers.

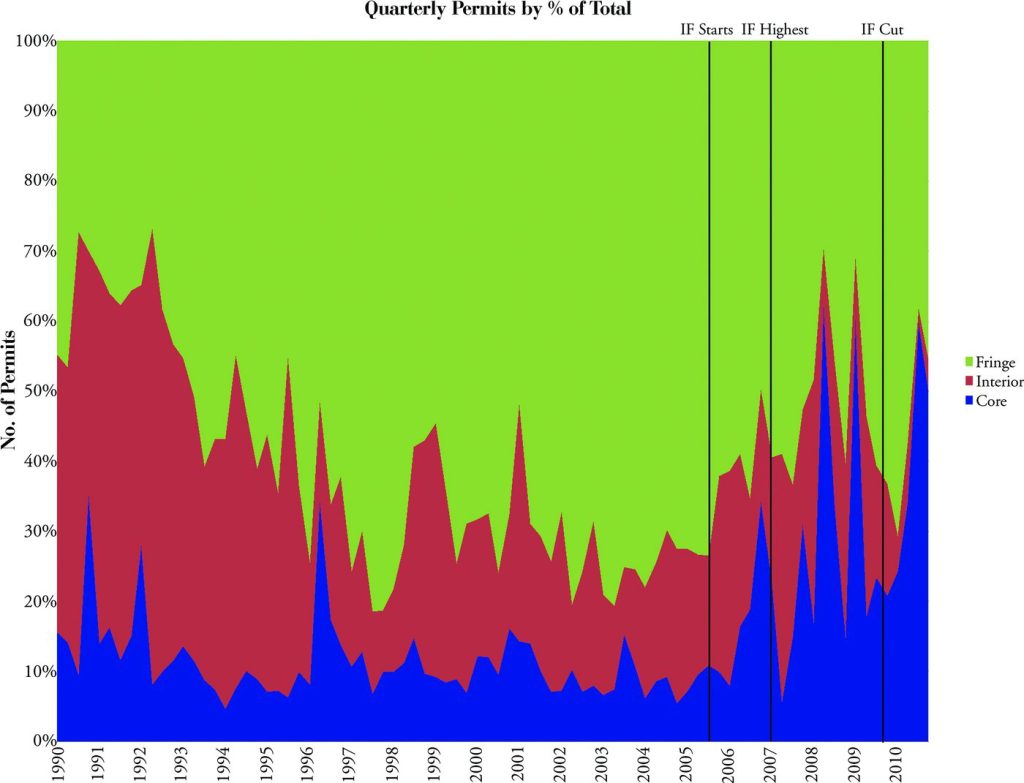

Other cities have pursued financial incentives. In 2005, Albuquerque adopted an impact fee policy that imposed higher fees in fringe locations to reflect the cost of extending infrastructure, while waiving fees in designated development zones. A study of the program between 2005 and 2013 found it successfully reduced permitting at the urban fringe, thereby limiting sprawl. However, the policy did not stimulate growth in Albuquerque’s urban core; much of the would-be fringe development simply moved into adjacent jurisdictions (Burge et al. 2013). This suggests that while impact fees can mitigate sprawl, they are insufficient to induce substantial infill without coordinated regional planning.

At the municipal level, incentive zoning may offer a more targeted alternative. While most commonly used to provide density bonuses for affordable housing (Homsy and Kang 2022), some cities have leveraged it to support revitalization and sustainability goals. Ann Arbor and Asheville, for example, have successfully used incentive zoning to promote infill growth in their urban cores (Homsy 2015).

These case studies highlight that policy tools for promoting infill—whether zoning adjustments, streamlined approvals, or financial incentives—must be designed with both regulatory and market realities in mind. Upzoning or incentives alone are rarely sufficient; successful programs typically combine flexible regulations, targeted financial measures, and attention to local development dynamics.

New Jersey

As the densest state in the U.S., New Jersey has little room to grow without sacrificing green space or encroaching on wetlands. At the same time, the state faces a severe housing shortage, with the Department of Community Affairs projecting a need for 84,698 new affordable homes over the next decade. To address this shortage while limiting land consumption, infrastructure costs, and congestion, infill development—particularly around rail and bus corridors—offers the most practical path forward.

The New Jersey State Development and Redevelopment Plan (Draft Final State Plan as of September 15, 2025) underscores this approach. Its housing goal emphasizes “promoting an adequate supply of high-quality housing…in transit-rich locations” while encouraging land preservation. Its “Revitalization and Recentering Goal” similarly calls for restoring vacant and abandoned properties and redesigning underutilized areas for private development and investment. To advance these objectives, the plan recommends reducing parking footprints by building on underused lots, revisiting restrictive local land use policies, and fast-tracking conforming development applications (New Jersey 2025).

Recent development trends reinforce the need for this shift. Research shows that since 2007, growth in New Jersey has moved from the exurban fringe toward the urban core. Newly developed land peaked at more than 18,000 acres per year between 2002 and 2007 but dropped to about 3,500 acres annually between 2012 and 2015. While overall housing production declined after the 2008 financial crisis, other measures indicate a major shift: before 2007, less than 5 percent of population growth occurred in areas more than 90 percent built out, compared to nearly 65 percent between 2007 and 2018 (Evans 2020).

Several tools already in use demonstrate how municipalities can support infill development. Transfer-of-development-rights (TDR) ordinances, for example, move development credits from environmentally sensitive areas to designated growth zones. Regional entities such as the Pinelands Commission and the Meadowlands Commission have employed TDR to preserve open space, as have municipalities like Chesterfield and Lumberton (Listokin 2007).

Another widely used tool is the Payment in Lieu of Taxes (PILOT) program, which grants 30-year tax abatements for projects in redevelopment zones. Municipalities have applied PILOTs to a variety of infill projects, including brownfield remediation (the 374-unit Somerville Station complex), parking lot redevelopment (the under-construction 300-unit Woodmont Rail at Metropark), and vacant land reuse (the 240-unit redevelopment of a Princeton Theological Seminary site) (NJTOD 2025). By offering financial incentives, PILOTs not only attract investment to infill sites but also allow municipalities to secure new revenue from previously underutilized properties.

Compared to impact fees—which discourage fringe development but leave urban areas unaffected—PILOTs directly incentivize targeted growth. A smart growth strategy for New Jersey could involve combining both approaches: using impact fees to steer development away from the fringe while deploying PILOTs to actively channel investment into the urban core.

New Jersey’s experience demonstrates that infill development can be advanced through a combination of regulatory guidance, strategic incentives, and careful land-use planning. Coordinated policies that align housing needs, transit access, and environmental preservation are key to addressing the state’s housing shortage without sacrificing green space or overburdening infrastructure.

Key Takeaways

Existing research on infill demonstrates that it generates financial, environmental, and social benefits. Concerns that infill reduces property values are largely unsupported; in some cases, studies suggest that it can even increase nearby property values. At the same time, infill presents challenges, including the need for careful stormwater management and the difficulty of producing affordable housing without additional policy supports.

To promote infill, municipalities have relied on tools such as upzoning, impact fees, incentive zoning, and TDR. Evidence indicates that combining strategies—using impact fees to discourage fringe development while deploying PILOTs to incentivize investment in urban cores—can more effectively steer growth toward desired areas.

As New Jersey seeks to address its housing shortage while limiting the negative externalities of sprawl, infill emerges as a highly practical and strategically advantageous approach, balancing density, environmental protection, and community revitalization.

Cited

Brunes, Fredrik, Cecilia Hermansson, Han-Suck Song, and Mats Wilhelmsson. “NIMBYs for the Rich and YIMBYs for the Poor: Analyzing the Property Price Effects of Infill Development.” Journal of European Real Estate Research 13, no. 1 (2020): 55–81. https://doi.org/10.1108/JERER-11-2019-0042.

Burge, Gregory S., Trey L. Trosper, Arthur C. Nelson, Julian C. Juergensmeyer, and James C. Nicholas. “Can Development Impact Fees Help Mitigate Urban Sprawl?” Journal of the American Planning Association 79, no. 3 (2013): 235–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2014.901116.

Carswell, Andrew. “Do Infill Properties and Major Property Improvements Create Externalities That Impact Property Taxes?” Journal of Property Tax Assessment & Administration 14, no. 1 (2017): 5–18.

Cervero, Robert, G. B. Arrington, Transportation Research Board, Transit Cooperative Research Program, and Transportation Research Board. Effects of TOD on Housing, Parking, and Travel. National Academies Press, 2008. https://doi.org/10.17226/14179.

Evans, Alan. Economic & Land Use Planning. Blackwell Publishing, 2004.

Evans, Tim. “Redevelopment Is the New Normal.” New Jersey Future, 2020. https://www.njfuture.org/2020/06/12/redevelopment-is-the-new-normal/.

Felt, Emily. “Patching the Fabric of the Neighborhood: The Practical Challenges of Infill Housing Development for CDCs.” Working Paper Series (Harvard University Joint Center for Housing Studies), no. 4 (2007): 67.

Gabbe, C. J., Michael Kevane, and William A. Sundstrom. “The Effects of an ‘Urban Village’ Planning and Zoning Strategy in San Jose, California.” Regional Science and Urban Economics 88 (May 2021): 103648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2021.103648.

Grimm, Nancy B., Stanley H. Faeth, Nancy E. Golubiewski, et al. “Global Change and the Ecology of Cities.” Science 319, no. 5864 (2008): 756–60. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1150195.

Hamilton, Cathryn, and Jon Kellett. “Cost Comparison of Infrastructure on Greenfield and Infill Sites.” Urban Policy and Research 35, no. 3 (2017): 248–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/08111146.2016.1274257.

Haninger, Kevin, Lala Ma, and Christopher Timmins. “Estimating the Impacts of Brownfield Remediation on Housing Property Values.” SSRN Electronic Journal, ahead of print, 2012. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2469241.

Hogue, T, C Panos, J McCray, and R Gilliom. “Stormwater Infrastructure at Risk: Predicting the Impacts of Increased Imperviousness Due to Infill Development in a Semi-Arid Urban Neighborhood.” American Geophysical Union, 2017.

Homsy, George. “Incentive Zoning: Understanding a Market-Based Planning Tool.” Public Administration Faculty Scholarship 5 (2015).

Homsy, George C., and Ki Eun Kang. “Zoning Incentives: Exploring a Market-Based Land Use Planning Tool.” Journal of the American Planning Association 89, no. 1 (2023): 61–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2022.2050935.

Jun, Hee-Jung, Dohyung Kim, Ji-Hwan Kim, and Jae-Pil Heo. “Detection of Infill Development and Contributing Factors Using Deep Learning and Multilevel Modeling.” Cities 150 (July 2024): 105019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cities.2024.105019.

Keith, Wiley. “An Exploration of the Impact of Infill on Neighborhood Property Values.” Doctoral Dissertation, University of Maryland, Baltimore County, 2009.

Kim, Jae Hong, Douglas Houston, Jaewon Cho, Ashley Lo, Shi Xiaoxia, and Andrea Huff. Infill Dynamics in Rail Transit Corridors: Challenges and Prospects for Integrating Transportation and Land Use Planning. UCTC FR 2016 06. California Department of Transportation, 2016.

Lambin, Eric F., and Patrick Meyfroidt. “Global Land Use Change, Economic Globalization, and the Looming Land Scarcity.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108, no. 9 (2011): 3465–72. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1100480108.

Listokin, David, Carole Walker, Reid Ewing, Matt Cuddy, Matthew Camp, and Jennifer Senick. Infill Development Standards and Policy Guide. Center for Urban Policy Research. Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning & Public Policy, 2006.

Loo, Becky P. Y., Amy H. T. Cheng, and Samantha L. Nichols. “Transit-Oriented Development on Greenfield versus Infill Sites: Some Lessons from Hong Kong.” Landscape and Urban Planning 167 (November 2017): 37–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2017.05.013.

Lynch, Eric. Cost of Constructing a Home-2024. National Association of Home Builders (NAHB), 2025.

McConnell, Virginia, and Keith Wiley. “Infill Development: Perspectives and Evidence from Economics and Planning.” In The Oxford Handbook of Urban Economics and Planning, 1st ed., edited by Nancy Brooks, Kieran Donaghy, and Gerrit‐Jan Knaap. Oxford University Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195380620.013.0022.

Merlin, Louis A. “The Influence of Infill Development on Travel Behavior.” Research in Transportation Economics 67 (May 2018): 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.retrec.2017.06.003.

Mustafa, Ahmed, Martin Bruwier, Pierre Archambeau, et al. “Effects of Spatial Planning on Future Flood Risks in Urban Environments.” Journal of Environmental Management 225 (November 2018): 193–204. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2018.07.090.

Newbold, Tim, Lawrence N. Hudson, Samantha L. L. Hill, et al. “Global Effects of Land Use on Local Terrestrial Biodiversity.” Nature 520, no. 7545 (2015): 45–50. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14324.

Ngo, Nicole S., Zhenpeng Zou, Yizhao Yang, and Edward Wei. “The Impact of Urban Form on the Relationship between Vehicle Miles Traveled and Air Pollution.” Transportation Research Interdisciplinary Perspectives 28 (November 2024): 101288. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trip.2024.101288.

NJTOD. “What’s Taxes Got to Do with It? Exploring PILOTs.” 2025. https://www.njtod.org/exploring-pilots/.

Nygaard, Christian A., George Galster, and Stephen Glackin. “The Size and Spatial Extent of Neighborhood Price Impacts of Infill Development: Scale Matters?” The Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics 69, no. 2 (2024): 277–306. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-022-09916-x.

Pollakowski, Henry, David Ritchay, and Zoe Weinrobe. “Effects of Mixed- Income, MultiFamily Rental Housing Developments on Single-Family Housing Values.” Massachusetts Institute for Technology-Center for Real Estate, 2005.

Quattro, Christine, and Esteban López Ochoa. “Zoning for Infill Development: San Antonio’s Create-Your-Own Zoning District.” Journal of the American Planning Association 91, no. 3 (2025): 465–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/01944363.2024.2442050.

Ratto, Peyton. “Estimating the Impact of Infill Housing on Reduction in Vehicle Miles Traveled.” Master’s Thesis, California Polytechnic State University, 2023.

Salon, Deborah, Marlon G. Boarnet, Susan Handy, Steven Spears, and Gil Tal. “How Do Local Actions Affect VMT? A Critical Review of the Empirical Evidence.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 17, no. 7 (2012): 495–508. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2012.05.006.

The Preliminary Draft of the New Jersey State Development and Redevelopment Plan. New Jersey State Planning Commission, 2025.

Thorne, James H., Maria J. Santos, Jacquelyn Bjorkman, et al. “Does Infill Outperform Climate-Adaptive Growth Policies in Meeting Sustainable Urbanization Goals? A Scenario-Based Study in California, USA.” Landscape and Urban Planning 157 (January 2017): 483–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2016.08.013.

Tuffour, Justice P., Reid Ewing, Simon Brewer, and Guang Tian. “Do Mixed-Use Developments Optimize VMT and Emissions Reduction? Evidence from 36 Regions.” Transportation Research Part D: Transport and Environment 147 (October 2025): 104944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trd.2025.104944.

Zhang, Kai, and Stuart Batterman. “Air Pollution and Health Risks Due to Vehicle Traffic.” The Science of the Total Environment 0 (April 2013): 307–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.01.074.