Form-based code is a method of regulating development to achieve a specific urban form. Form-based codes create a predictable public realm by controlling physical form primarily, with a lesser focus on land use, through city or county regulations.

Form-based codes address the relationship between building facades and the public realm, the form and mass of buildings in relation to one another, and the scale and types of streets and blocks. The regulations and standards in form-based codes, presented in both diagrams and words, are keyed to a regulating plan that designates the appropriate form and scale (and therefore, character) of development rather than only distinctions in land-use types. This is in contrast to conventional zoning’s focus on the segregation of land-use types, permissible property uses, and the control of development intensity through simple numerical parameters (e.g., FAR, dwellings per acre, height limits, setbacks, parking ratios). Not to be confused with design guidelines or general statements of policy, form-based codes are regulatory, not advisory.

—Definition from The Form-Based Code Institute

As many design professionals in New Jersey can attest, there are major issues that communities typically must address during the planning process to achieve a unified vision for their future. In the course of a transit-oriented development (TOD)-based planning effort by the Town of Dover, these “typical” issues were compounded by the need to accommodate an ethnically and culturally diverse community. To accomplish this, the town hired Heyer, Gruel and Associates (HGA) of New Brunswick to engage all the stakeholders, including marginalized minority populations, to produce an inclusive plan.

HGA built upon NJ TRANSIT’s 2003 Transit-Friendly Station Area Vision Plan. The consensus building approach was chosen to target traditional community groups such as the civic associations, leaders, and community service organizations, as well as groups with Hispanic and Latino members. HGA found that the most effective portion of the project was one-on-one stakeholder interviews. These interviews allowed individuals to feel comfortable in expressing their opinions, free from the reactions of those with opposing viewpoints. Furthermore, this process allowed planners to dispel myths associated with development through direct education.

The planning task in Dover was to develop a new comprehensive Master Plan including a Fair Share Housing Plan consistent with smart growth planning principles, and to incorporate a more detailed TOD plan for the area within ¼- and ½-mile radii of the Dover train station. The TOD effort was centered on the community’s historic core which contains the downtown business district and its civic uses, the train station, a former urban renewal site, surface parking lots, a partially defunct freight line with a dozen at-grade unprotected street crossings, and the Rockaway River. The challenge was to pull together these attributes in a way that added value to the community while recognizing the rail ridership potential of Dover station.

Design and consensus building have long been recognized as important elements in the planning process. Many citizens, however, have difficulty envisioning how their input will translate into physical improvements and community policies. The public also struggles to translate planning jargon into a vision it can truly understand. Furthermore, people come to these meetings with engrained biases that are difficult to unravel—but these biases must be addressed for any planning process to move forward. To tackle these preconceptions head on, HGA graphically depicted exactly how best to build valuable transit-oriented development that, despite the larger issues at play, could be implemented. To achieve consensus, all groups were engaged in a form-based approach—an approach that visually communicated the message that good design was paramount to the town’s future.

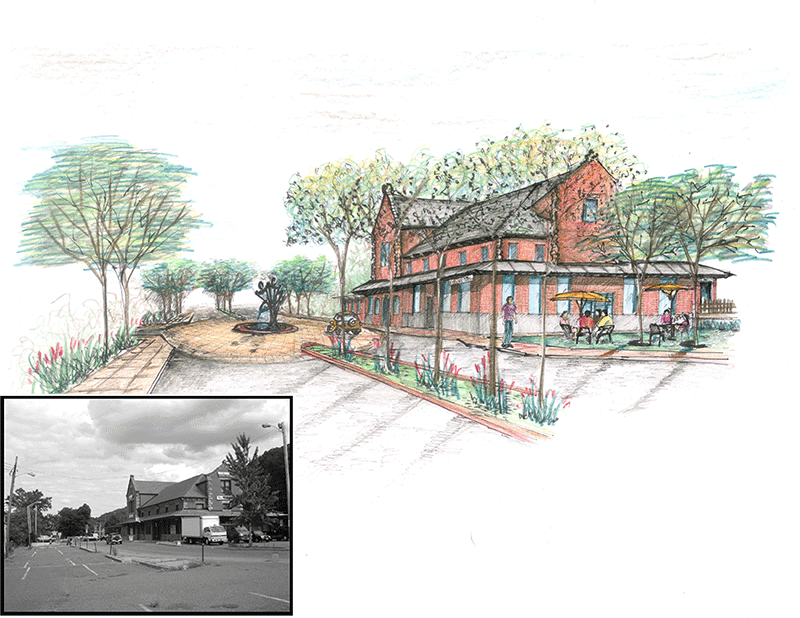

Rather than employing conventional use designations and density calculations, HGA’s overall vision was based in “form” and functional relationships. The firm used in-fill renderings and simulations based on photographic imagery of Dover; these permitted people to see how their policies would shape the community and how a new building would look next to those they see everyday. As a result, the presentation was made more effective because it enabled the public to process the plan both verbally and visually.

This approach is in contrast to the reactive planning model, prevalent for some time now, that has typically responded to immediate concerns and often offers only “quick fixes” to stem public outcry over perceived ills associated with local property taxes. This approach invariably tends to be “penny-wise and dollar foolish,” producing short-term fixes generally aimed at strengthening the tax base, but adding little to no value to surrounding properties and the community at large. Further, the reactive model tends to produce poorly scaled, auto-dependent, single-use projects—the likes of which are the by-product of traditional Euclidean zoning. As one New Jersey public official aptly put it, “The current approach toward development privatizes profit and socializes the cost without the general public knowing it.”

Form-based planning requires the public and local officials to be willing to listen, keep an open mind and look at the long term. Discussions of floor-area ratios, number of stories, and densities all have the ability to become contentious issues when numerical values alone start being perceived as good or bad, without recognition of what the numbers translate to in “on-the-ground” development. When such situations arise, the importance and need for graphical representations becomes clear.