This is Part 2 of our series on how public spaces contribute to transit-oriented community life. Here we will discuss how residents, planners, and developers can help to create these spaces. Please also see Part 1: Public Spaces Add Vitality to Transit-Oriented Communities.

As discussed in Public Spaces Add Vitality to Transit-Oriented Communities, public spaces can bring people together who live, work, and play in the same place, help improve physical health and mental well-being, provide equitable access to amenities, support redevelopment, and increase safety. In this companion article, we will explore ways to create inclusive and well-functioning public spaces in transit-friendly locations.

Create a Sense of Place

A strong sense of place is fundamental to the creation of community. There may be no better way to convey collective identity or a communal bond than through a shared place and an understanding of its history. Placemaking—the local and collaborative process used to shape or reinvent public spaces while preserving physical, cultural, and social identities that define those places—can help to bolster the community-supportive properties of parks and public space and can be employed throughout a downtown, in a transit area, or in other public spaces. When invigorated by placemaking techniques, these places connect individuals to each other and with the past. Good planning generally, and placemaking specifically, improves connections between existing places, recently reinvented places, and newly-created places with what happens around and adjacent to them, namely, development and redevelopment.

Place can be seen as a creation of architecture whose purpose is to make the individual more embedded in the community, and in the world.

Karsten Harries, 1996, The Ethical Function of Architecture.

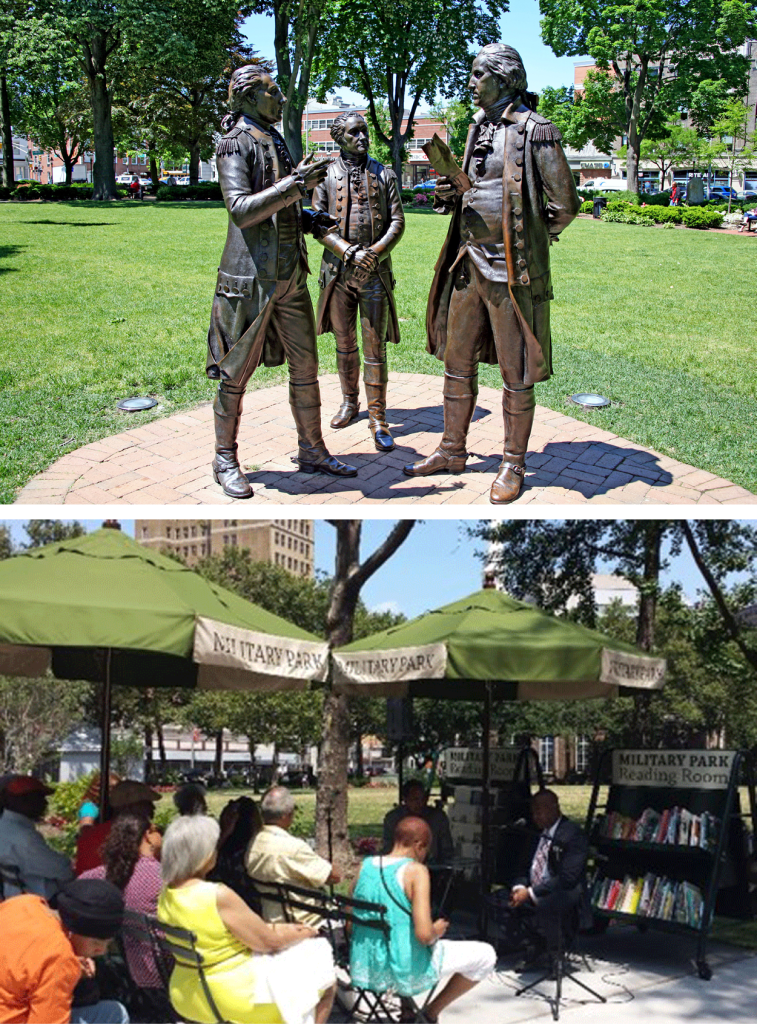

This process of creating a sense of place can be seen in an iconic town square like Morristown Green. The former site of the Morris County courthouse and jail, as well as numerous historic, political, cultural, and military events, the Morristown Green now serves as the town’s gathering place, and the site of the community’s Winter Holiday celebration and its farmers market. Its historic statues and plaques tell the story of Morristown’s history, particularly its role in the American Revolution, and engage and attract visitors from near and far.

The 2014 redesign of Military Park in Newark allowed it to reclaim its role as the city’s town square. New signage details free activities and events offered, plaques identify historic statues in the park, and moveable seating branded with the words “Military Park” accommodate the needs of all users.

Plan and Implement Community-Driven Goals

The decision to create or improve a public space hinges on a number of factors. A public planning process focused on redevelopment, on improvements to local health and safety, or on an underutilized community asset is particularly important. Once a need for more public space has been identified, community members can work together with stakeholders, planners, and developers to achieve their goals. In Metuchen, years of discussion—focused on downtown redevelopment and more intensive use of station area parking lots—helped the community identify the need for a central gathering place. Metuchen had this goal in mind while working with Woodmont Properties to plan the redevelopment of the Park Street Parking Lot mixed-use project. This collaboration resulted in a European-style plaza designed to serve as a public square for the borough. The plaza hosted its first large public event this past New Year’s Eve and will be the site of other large events, as well as community fitness classes and other activities.

Early input from the public is essential to ensure that the resulting plans have the wide support they need to be implemented. This is often a missing step in the process used by many communities, resulting in preventable delays and a failure to implement. Early public input is an important part of the Community Planning Assistance Program (CPAP) run by the New Jersey Chapter of the American Planning Association. Tom Schulze, CPAP Coordinator, advises that “creating adequate opportunities for community input is time-consuming and best accomplished over the long term, so stakeholders become more familiar with the issues and can provide realistic and workable solutions.”

If a municipality does not have the funds to acquire land or the property available to build a new park or public space, it may want to consider using inducements or “incentive zoning” to encourage developers to incorporate these elements into their plans. Incentive zoning provides a bonus to developers—often permission to build at a greater density or height than permitted by established zoning—in exchange for providing a specific community benefit. In certain zones, Seattle permits commercial and residential developers extra floor area when they include affordable housing, childcare centers, and other public amenities such as open space and green street improvements. New York City’s incentive zoning program dates to 1961. In 2007, New York City revised the program and added quality standards to ensure public spaces provide useful and desired amenities for public space users. In addition to the design and construction of these public spaces, developers can provide fitness-oriented amenities or support for park or plaza management.

Location, Location, Location … or Bring Public Space to a Transit Area Near You

Source: Art on Division

Parks and public space strategically located near transit facilities can create synergies that sustain the use of both. Military Park in Newark sits midway between the city’s two railroad stations—Newark Penn and Newark Broad Street—and along multiple bus routes. The park offers those traveling to and from either station an ideal location to relax or to recreate in the morning, during a lunch break, or at the end of the day. It also serves as the “front yard” for some of the city’s redevelopment efforts, such as the New Jersey Performing Arts Center, the Prudential Tower (completed in 2015), and the recently completed adaptive reuse of the Hahne & Company department store.

In Somerville, upgrades to a connector between the downtown and the Somerville Train Station initially focused on widening sidewalks and other improvements and led to a “shared street” where all users—pedestrians, bicyclists, and drivers—share the road. To facilitate the shared street, designs called for raising the road surface to the sidewalk elevation, which was completed in 2012. Poured concrete used for this project required a two-month curing period, during which time the space was pedestrian-only. This unintentional pilot of a pedestrian-only space struck a chord with residents and visitors, who called for additional consideration of use of the space. A survey conducted in summer 2013 confirmed local preferences and resulted in the state’s sole pedestrian-only street. Somerville’s Division Street is now an actively programmed space in the heart of the community. Somerville Downtown Alliance, the community’s Main Street organization, and Arts on Division, a community-based group promoting art and art education, host frequent events in the space.

Source: Transbay Joint Powers Authority

One strategy to bring public spaces into a transit-oriented community is to build a park or plaza at (or on top of) a transit facility. The redevelopment of San Francisco’s Transbay Center makes such public space a priority. With the completion of its first phase in summer 2018, the new Transbay Center will connect eight Bay Area counties through 11 transportation systems, including AC Transit, BART, Caltrain, Golden Gate Transit, Greyhound, Muni, SamTrans, WestCAT Lynx, Amtrak, Paratransit, and the High Speed Rail Authority, which will eventually connect San Francisco to Los Angeles/Anaheim. The Center will feature Salesforce Park, a 5.4-acre rooftop public park that will serve station visitors, nearby office workers, and local residents. The park will feature an open-air amphitheater, gardens and trails, children’s play space, public programming, events, a restaurant, and a café.

Fund Public Space Projects

Securing the resources to improve, create, or program public space may require creativity, ingenuity, persistence, and, possibly, a bit of luck. Funding can come from many sources, both public and private. Public resources include county and state open space grants such as the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection Green Acres Program; the Bergen County Open Space, Recreation, Floodplain Protection, Farmland and Historic Preservation Trust Fund; and the Morris County Open Space Trust Fund. Some non-profit and private sector organizations offer grants for operations, construction, and general administrative costs or for specific initiatives, such as free fitness classes. New Jersey grant-making organizations with a history of supporting similar projects include the Community Foundation of New Jersey, the Horizon Foundation for New Jersey, and the Victoria Foundation. Still another option may be working with a dedicated private sector partner with a history of philanthropic investment focused on public space, fitness, and/or public health. Such collaborations can be used to fund construction or establish a dedicated management group for the public space.

Communities may also want to consider using a crowdfunding platform such as “ioby”. “ioby” stands for “In Our Back Yard” and can be used to support citizen-led, -designed, -funded, and -implemented projects. The Metuchen Downtown Alliance (MDA), the borough’s downtown management corporation, led a successful crowdfunding campaign to secure $2,500 to support their efforts. These funds, together with an additional $2,500 in matching funds from National Main Street Center’s Edward Jones “Placemaking on Main Crowdfunding Challenge,” allowed the MDA and other community members to transform a neglected parking lot into a thriving, family-friendly public space (see the video). This success has spurred MDA to use crowdsourcing again, in this case to support Innovation Alley, a demonstration parklet that connects Main Street with mid-block parking.

Ongoing support for public space operations may also come from a variety of sources including grants, event use fees, sponsorship, and contributions from abutting property owners and businesses that benefit from its success. Many grants are multi-year or startup grants that allow non-profit organizations to get off the ground successfully. One-off grants are also available from a variety of groups such as the Turrell Fund. User fees can be charged when groups wish to utilize public space for private events and can be scaled according to event type. Communities looking to provide certain amenities, such as public programs or a free Wi-Fi network, may seek sponsorship from groups interested in advertising in the public space. Finally, surrounding property owners that benefit from a public space’s activation and increased pedestrian traffic could be asked to contribute annually to ensure the public space’s continued success. Newark’s Military Park is partially funded by contributions from nearby businesses, including Prudential and PSE&G.

Manage Public Space

A public space management entity is one way to invest in, or revitalize, a public space. Such an entity could be the local parks or recreation department, an existing local non-profit organization, a new non-profit organization dedicated to community public space, or a Business Improvement District (BID). If the funding exists, and if the size and scope of services in a public space seem large enough, a non-profit organization can be formed specifically to oversee a specific public space.

Source: Lauren Beicher

In Metuchen, the MDA cultivates public spaces as part of its mission as a downtown management organization. The Borough’s New Year’s Eve celebration was followed in late May by a “Pre-Prom Party” on the Metuchen Town Plaza where members of the Metuchen High School Class of 2018 and their friends and family gathered before Senior Prom. MDA Executive Director, Ian Kremer, believes it is important to have an active group managing the space. He says “it takes a lot of work to curate, provide experiences, and inject an element of happiness into the space. We’re giving people a reason to come back.” The MDA also works with a commercial cleaning contractor to keep the spaces clean and welcoming.

Kremer advises other communities to also consider the value of “experiential retail” to welcome and attract consumers through experiences such as exhibitions or pop-up shops. “We encourage small businesses to be engaged stakeholders of these spaces and demonstrate to them how it affects their bottom line.”

Managers of public space may also organize regular community activities such as free fitness classes. Newark’s Military Park, for example, offers over 18 free weekly fitness classes to the community in the spring and summer. Classes attract a mix of participants including office workers, residents, tourists, and students. Somerville’s Division Street is the site of numerous events including Somerville Summer Stage held each Saturday from Memorial Day through Labor Day.

Inclusive and well-functioning public spaces are an essential part of transit-oriented communities. When the transit system and public spaces seamlessly integrate with each other, they help to create places that connect users with each other, to their locality, and with the wider world. Through community-driven planning and implementation, municipalities through the state and the nation have created public spaces that provide amenities that help to support healthy lifestyles and integrate development and redevelopment into existing environments. Public spaces—the parks and plazas as well as the streets and other places in-between that connect the buildings that comprise our towns—contribute to the quality of places. By actively planning these spaces, communities can better connect their transit facilities to the rest of the community, improve the quality of life of residents and visitors, and help to create vibrant transit-oriented places.

For more on ways that public spaces contribute to transit-oriented communities, see Part 1: Public Spaces Add Vitality to Transit-Oriented Communities.

For More on Public Spaces

Garvin, A., 2011. Public parks: The key to livable communities. New York: WW Norton.

Harries, K. 1996. The Ethical Function of Architecture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Larson, L. R., Jennings, V., & Cloutier, S. A. 2016. Public Parks and Wellbeing in Urban Areas of the United States. PLoS ONE, 11(4).

Whyte, W.H., 1980. The social life of small urban spaces. Washington, D.C.: The Conservation Foundation.

Biederman Redevelopment Ventures

Design Trust for Public Space

National Recreation and Park Association

National Parks Conservation Association

National Park Foundation

Project for Public Spaces

The Trust for Public Land