Rutgers Regional Report: The ‘Burbs’ Bounce Back: ‘Trendlet’ or ‘Dead Cat Bounce’?. (2018). James W. Hughes, Joseph J. Seneca, and Will Irving, Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy

A new regional report examines whether a recent increase in suburban population in the New York metropolitan region is an irregularity or a notable shift from a larger, post-2010 reurbanization trend.

Published by the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy at Rutgers University since the late 1980s, the Rutgers Regional Report is a periodic series of monographs examining economic, demographic and planning issues important to the State of New Jersey. The latest report, entitled “The ‘Burbs’ Bounce Back: ‘Trendlet’ or ‘Dead Cat Bounce’?,” details the increase in suburban population between 2016 and 2017 following a rapid decline over the previous 10 years.

Throughout the report, the authors warn that the data indicating a new trend towards suburban revitalization was only measured over the course of one year, so any conclusions drawn must be reexamined in the future.

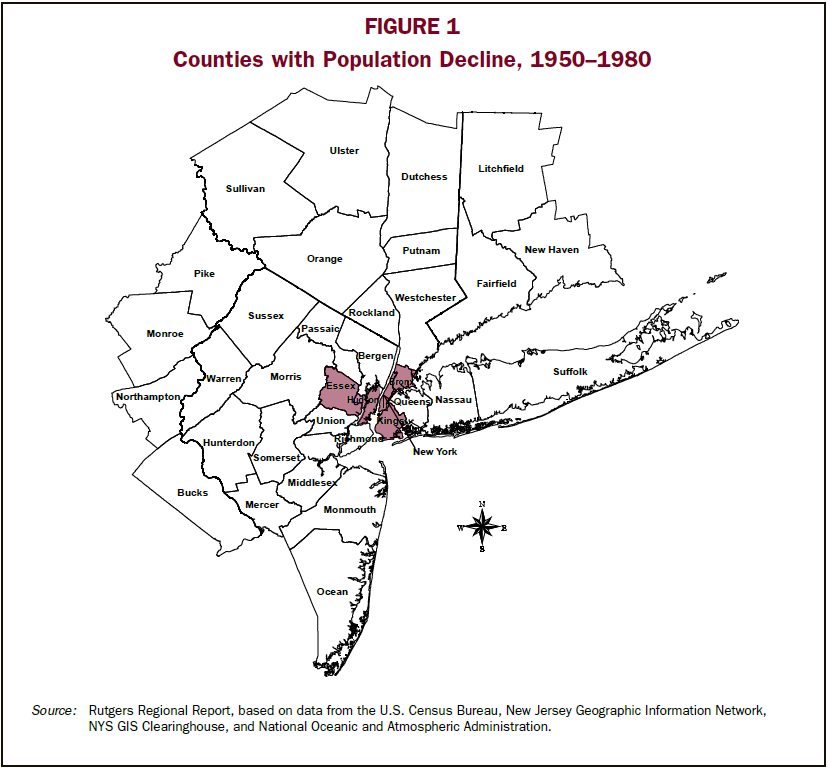

The report studied a total of 35 counties in Connecticut, New Jersey, New York, and Pennsylvania that comprise the New York City metropolitan area. The report splits the area into two categories: the regional core, which encompasses Manhattan and its seven surrounding counties, and the suburban ring of the remaining 28 counties. It compares the population change in this region during two time periods: 1950-1980 (post-World War II, a period of massive suburbanization) and 2010-2017 (post-recession, a period of massive reurbanization). During the latter time frame, the report finds that the period from 2016 to 2017 saw an irregularity in the reurbanization pattern: the suburban ring accounted for almost 62 percent of the region’s total population gain of 51,746 persons, while the regional core accounted for only 38 percent.

The authors attribute this deviation to increased housing costs and aging transportation infrastructure in the urban core, and older millennials seeking suburban living for child rearing.

These trends all have important implications for those concerned with transit-oriented-development. Deteriorating transit infrastructure could be causing outmigration to the suburbs and could affect development in downtowns. Communities may look to increase efforts to preserve and expand affordable housing options and to expand the types of housing offered in TODs to be more welcoming of young families.

The report makes clear we cannot determine exactly what the outcomes of recent suburban population increases will be. However, we can examine the factors that made the suburbs more appealing during the 2016-2017 time period, and whether such trends will continue into the future. Poor urban school quality, expensive urban housing costs, and relatively cheap gas prices incentivize people to move into the suburbs, and these conditions do not appear to be changing anytime soon. Additionally, if homeownership becomes as important to millennials as it was to earlier generations, the suburbs may become as attractive as they were before the recession. The suburbs have the potential to increase their attractiveness further by addressing the main issues that spurred the post-2010 migration to regional cores: low density, low job availability without a long commute, and little to no activity within neighborhoods appealing to young people.