While the world of finance may seem complex, it is an incredibly important aspect of development. In all cases, the financial details of a project dictate its scope—if and how it will be constructed, the amount of affordable housing it may contain, and the rate of return, which is important for non-profit and for-profit developers alike. The significance of such details lies in how they shape a project’s bottom line. Regardless of tax status, those looking to develop must grasp how finance translates vision into physical structures, determining both their aesthetic and functional qualities. To better understand transit-oriented development then, to discern the variables and considerations that fundamentally determine a finished product, we must explore the oft-overlooked world of development finance.

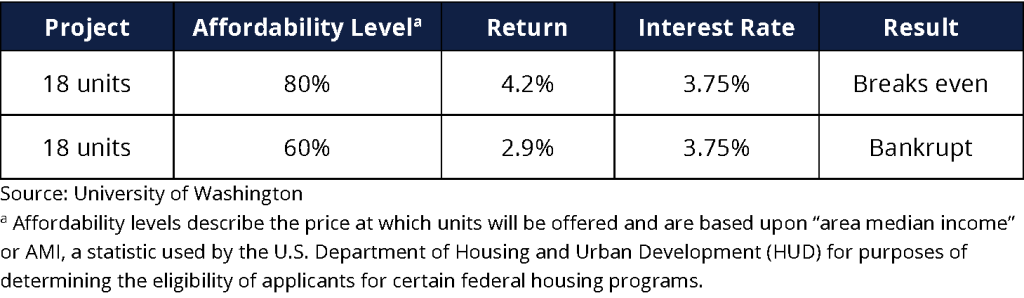

The following illustration demonstrates why financial matters are so important: In July 2021, the City of Seattle passed a new law allowing affordable housing to be built in underutilized church parking lots, but a key change in the resolution lowered the rents that could be charged from 80 percent Area Median Income (AMI) to 60 percent AMI. A University of Washington analysis of the new law found that the financing, even for a religious organization not looking to make a profit, became unfeasible with the change. Because money must be borrowed to pay for projects, at a current, typical interest rate of 3.75 percent, a 2.9 percent return from units restricted at 60 percent AMI would mean that the church would face expenses greater than the revenues derived from the project. See Table 1. If the rent for the new units was set at 80 percent AMI, however, the yield would be 4.9 percent—a razor thin margin keeping the church from losing money or needing to continually subsidize the project.

Table 1. Affordable Housing in Seattle

When looking at the financing of TOD, projects typically follow one of three distinct models, which will be explained consecutively, in detail, throughout this article:

- Private Development—Led by private business, typically creating market-rate housing, and, by far, the broadest category.

- Joint Development—When a transit agency partners with a private developer to create an improvement on agency-owned land, such as leasing park-and-ride space for a TOD.

- All-affordable TOD—A type of development in which private developers, non-profits, and/or government agencies create a project with entirely-subsidized units. This can also occur through Joint Development.

Today, private development operates by speculating on transit-adjacent land in tight markets, often redeveloping distressed, underperforming, and/or irregularly-sized parcels into predominantly mixed-use, luxury complexes. A rate of return on the investment of purchasing land and constructing a new building is achieved by charging high rents for the premium of nearby station access.

To some, this private capitalization on a public good causes concern, and, increasingly, municipalities have developed mechanisms to extract public value out of the developer’s efforts as well. For example, in dense, transit-rich Hoboken, an ordinance requires that developers allocate 10 percent of new units for affordable housing. While the intentions are sound, in some cases blanket requirements such as Hoboken’s can serve to stifle development—as when the “return on investment” (ROI) becomes too little to warrant the undertaking. A tool that Hoboken, and other cities, use to counter this issue is the density bonus that, in effect, allows the developer to build more units than otherwise permitted, provided that the affordable housing is included.

For transit-oriented development (TOD), different parties have different goals. For the city planning office, it might be densification, for political leadership it might be expanding the tax base, and for the developer it is, primarily, turning a profit. These goals may overlap and create tension with one another, which is usually manifested in the zoning appeals process. Understanding the financial dimension is crucial for advocates, community leaders, and anyone interested in the construction of housing near public transportation. Without knowledge of the financial nuances of development, we run the risk of advocating for poor policies that will inhibit equitable Transit-Oriented Development (eTOD).

The Process… Simplified

A typical development process can seem simple: a developer (for profit or non-profit), or a government agency, selects a parcel of land for a project. For a TOD, this site would be close to transit service, such as commuter rail, or a frequent bus. The purchase of land can involve creating a capital stack, in which debt is taken out (for example, via a bank), and equity given (i.e. to investors), to cover land and subsequent construction costs. After the lot is purchased, zoning must be considered. If the developer’s rate of return requires more units than are presently permitted, they must apply with the municipality for a rezoning or variance. These processes are often lengthy, requiring legal documents, hearings, and application fees. If successful, the developer can then proceed with construction, drawing on their capital stack for funds. The finished project’s return must be able to cover land acquisition, debt service on the loans, payments to investors, zoning costs, construction (chiefly, labor and materials), and maintenance and operations costs.

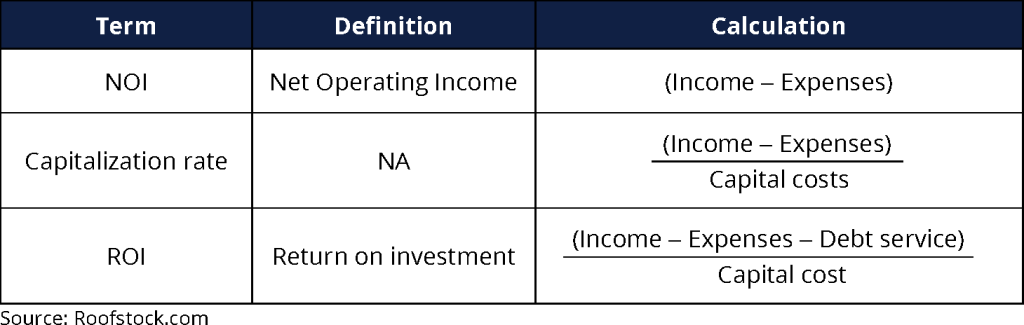

For these calculations, there are a few important terms: Net Operating Income (NOI), capitalization rate, and Return on Investment (ROI). Net Operating Income is calculated simply, by taking monthly income (such as rent payments from tenants), and subtracting operating expenses, but not debt payments. See Table 2.

Table 2. Key Real Estate Terms

The NOI can also be used to find the capitalization rate of a property, by dividing this figure by the cost of the property, such as $80,000 / $1,000,000. This capitalization rate (8%), helps the developer to estimate their expected income, as well as how long it will take to pay their initial investment off.

Return on Investment (ROI), like capitalization rate, is commonly used in the development field. This metric considers financing (such as debt service), showing the value of an investment over time with additional expenses. Its calculation is simple, dividing cash flow (income minus expenses, including mortgage payments) by the total investment cost. To compare capitalization rate with ROI, using the same, earlier figures, we can find that a $50,000 monthly cash flow (assuming a hypothetical $30,000 monthly mortgage payment), divided by $1,000,0000, shows a five percent ROI—well below the standard 15 percent that is often sought.

These terms are important because their calculation determines the outcome of a housing project, whether a developer will choose to invest in a property or not. Even in the case of affordable housing in Seattle, the rate of return must exceed the interest rate, or else there is risk of plunging the institution into bankruptcy.

Private Development

Consider a transit adjacent tract in Hoboken, near the Hudson-Bergen Light Rail. A private developer notices that the industrial property has fallen into disrepair and sees an opportunity. Before making a purchase, the developer will calculate the economic feasibility of the project to determine whether the upfront capital costs, such as land acquisition and construction, would be warranted. Besides construction and real estate, other costs must also be considered, such as taxes. In this hypothetical scenario, the developer might choose to forgo the project, because, with taxes considered, the ROI is too low.

In this instance, a developer might work with the municipality to try to obtain a tax abatement. While a high-demand area might not typically need incentives, many projects around the state use tax abatements, termed PILOTs (Payment in Lieu of Taxes), to persuade developers to invest. For example, MAS Development’s recent Vinty complex in Elizabeth, located near the train station in a redevelopment zone, received a PILOT agreement with the City.

Another consideration that affects a private developer’s decision to build are the local zoning requirements, exemptions to which are often sought. From the outset, some developers do not wish to invest the time or resources in local planning board petitions and choose to look elsewhere. Others may hire an attorney and engage in the months- or years-long process of receiving variances, which drives up overall costs. Minimum parking mandates—requirements that exist in most U.S. cities and that specify a minimum number of parking spaces based upon the number of housing units, bedrooms within units, and/or square footage—can also drive up the cost of building. Typically the cost of a space ranges between $5,000 and $10,000 for surface parking and much more for structured and subterranean parking.

Finally, the hypothetical private developer in Hoboken, who may have decided to press forward with the project, must also satisfy the requirement to reserve ten percent of the new units for affordable housing, which return less than the market rate. The developer may raise the rent of all the other units to make up for lost revenue. Alternatively, a municipality can offer a density bonus. Here, the zoning for the structure might be exceeded, provided some of the excess space is used for affordable housing. In this way, the developer may defray the cost of these units by building more housing overall.

When considering the developer’s perspective, one might begin to surmise why most private TODs are constructed and offered at luxury prices. Some regulations limit the amount of housing that can be built (such as floor-area ratio requirements), and others (chiefly parking) add a cost that is passed on to consumers. This is not to say that some developers do not evade requirements, nor that the industry cannot be lucrative, but that, from a planner’s or policymaker’s perspective, understanding their position can be very useful for the purpose of creating better community-focused solutions.

In some cases, municipalities and transit agencies might lobby for and enact legislation that supports more development in a transit-adjacent area by, for example, eliminating parking requirements, or adding density bonuses or other zoning overlays to encourage denser development near a transit stop. In New Jersey, the Transit Village Initiative encourages municipalities to change their zoning to encourage mixed-use development. Municipalities with a designated transit village area are eligible for certain grants in support of these efforts.

Private development is inherently complex and context-sensitive, but these are some considerations that inform the actions of developers looking to build TODs. Although governments can use several tools to incentivize action from the private sector, developers will still consider the key metrics that drive their decision-making, namely ROI, capitalization rate, market strength as well as the regulatory environment and its incentives.

Joint Development

Joint development (JD), while similar in many respects to private development, is characterized as a public-private partnership (P3) between a transit agency and a developer. Typically, the transit agency owns a parcel of land, often acquired for construction staging or for operations, which is near a transit station and remains vacant or is no longer in use. The agency could repurpose and develop this underutilized land with the assistance of a development partner. For instance, the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (Metro) has been engaged in joint development projects across its stations for the past two decades. The One Santa Fe development, comprising 438 apartments, 78,000 sq. ft. of retail space, and a grocery store, was built on the site of a Metro storage and maintenance facility. The developer, Canyon-Johnson Urban Fund Investments, signed a 78-year lease with Metro for the parcel.

Metro articulates its position in the process in its Joint Development Policy (2021). Its most important economic consideration is its “Affordable First” policy, which calls for all new units to be constructed for persons ranging from Extremely Low Income to Moderate Incomes. The One Santa Fe project, constructed in 2015, before the Affordable First Policy was in effect, was built with 20 percent of homes reserved as affordable (88 of 438).

In joint development ventures, TOD remains an attractive investment for developers. “A TOD location can shift $1,000 a month from a car into rent,” as cited in the 2021 Transportation Cooperative Research Program (TCRP) Guide to Joint Development for Public Transportation Agencies. The economic principle at work is deemed the Location Efficiency Principle, in which, as proximity to the center increases, transportation costs decrease, while housing costs increase. This relationship is well-illustrated in the Center for Housing and Neighborhood Technology’s (CNT) interactive Housing and Technology (H+T) Index, which shows how location, and access to amenities and job centers, can shift the ratio of housing and transportation. Developers see the potential for profit, and transit agencies see an opportunity for a stable revenue source.

At the same time, some aspects of these projects present challenges. Rather than purchasing a property outright, a developer in JD leases the land, lowering capital costs, and providing a steady source of revenue for the transit agency. The 2021 TCRP Guide characterizes the different positions held by the two parties. The developer is looking to create value, while the transit agency might hope to build ridership, increase affordable housing stock, and pursue other non-transportation objectives in addition to creating a revenue stream. And, like TOD by private developers, the report singles out two economic obstacles to the JD process: parking and affordable housing. These factors dramatically affect the ROI and capitalization rates of the project, thereby potentially reducing the project’s feasibility.

In some cases, a JD project might be planned for the site of an existing park-and-ride facility— transforming a parking lot into a mixed-use development. At the same time, a transit agency may wish to retain a certain allotment of parking spaces to continue serving riders who drive to the station. Here, they might require a developer to construct new structured parking facilities, which could cost between $25,000 and $50,000 per space. These additional expenses affect a developer’s bottom line, potentially jeopardizing the agreement. Affordable housing requirements, too, when not fine-tuned, can prove troublesome: capital costs to construct affordable units are comparable to luxury ones, but the return a developer can expect is much smaller. Higher rents for market-rate units can subsidize the affordable portion, but, of course, limit the market for those units to certain segments.

The TCRP report recommends solutions broadly classified as: “Make the Pie Bigger” and “Make the Gap Smaller.” Negotiating density bonuses that increase the overall number of units would address the former, and pursuing a variety of gap financing sources from local, state, federal, and philanthropic entities would address the latter. By cobbling together (or “stacking”) outside funding to make up the difference, affordable housing can still be included in a JD, even in a soft market.

Other examples of additional revenue sourcing on the agency side include Tax Increment Financing (TIF) districts, such as the Transit Revitalization Investment District (TRID) in the East Liberty neighborhood of Pittsburgh. With infrastructure improvements, tax revenues typically rise, and through the TRID, the difference in pre- and post-improvement tax earnings is “captured” for a separate fund. This money could pay for further improvements, such as a street redesign or a housing project. In the Pittsburgh case, money went to the East Liberty TRID Revitalization Authority, which reconfigured a nearby street to allow traffic in both directions. In other cases, TRID (or TIF) funds are used to pay off amortized debt—a solid income stream means government agencies can take out loans to finance larger improvements, or the work that initially sparked change in the special tax district. In this way, other funding sources may supplement agreements between developers and transit agencies to make a large project possible. For further information on federal funding, the FTA has issued guidance on how its support may be used in conjunction with a joint development venture.

Joint development remains a popular manifestation of TOD in the United States, as transit agencies often find mutually beneficial arrangements with private developers. However, the TCRP Guide recommends that agencies assemble teams with robust real estate and development experience to adequately navigate the context-sensitive and financial complexities of the project—and to understand a developer’s perspective to ensure that projects deliver a sufficient return to the public and are also feasible for the private partner.

Affordable Transit-Oriented Development

An affordable transit-oriented development may take the form of JD or be led by another partner government agency. The finance of affordable units is complex, as there are a variety of funding mechanisms, as well as potential partners, for a project. Additionally, the level of affordability affects the bottom line; units reserved at the typical 80 percent Area Median Income (AMI) will provide a considerably different return than those reserved for households making 30 percent AMI. Affordable TOD typically manifests as a mixed-income property or with all units offered at below market rates. Recently affordable or eTOD has seen a shift towards more mixed-income projects due to concerns about reconcentrating poverty. Still many all-affordable TODs are still being planned and constructed today.

Regardless of the rate at which a unit will be offered, construction costs remain the same. However, not all developers of affordable housing look to make money. Some operate as non-profit or government organizations and seek to make positive social change, while others in the private sector engage with the process to reduce their tax liabilities, primarily through the use of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs), which can be bought from developers of affordable housing, and applied on an annual basis over a period to discount one’s taxes. A mixture of public and private funds is often used to subsidize the construction of affordable housing.

New Jersey examples of affordable TOD include:

- Parkview AP—townhomes sponsored by a nonprofit, paid for using Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTCs),

- Bayfront—a large-scale mixed-income project in Jersey City where the municipality is taking on the role of developer

- The Station at Grant Avenue—an all-affordable complex in Plainfield financed by the New Jersey Housing and Mortgage Finance Agency (HMFA)

More information on each of these projects can be found in NJ eTOD: How Asbury Park, Plainfield, and Jersey City Are Promoting Equitable Transit-Oriented Development.

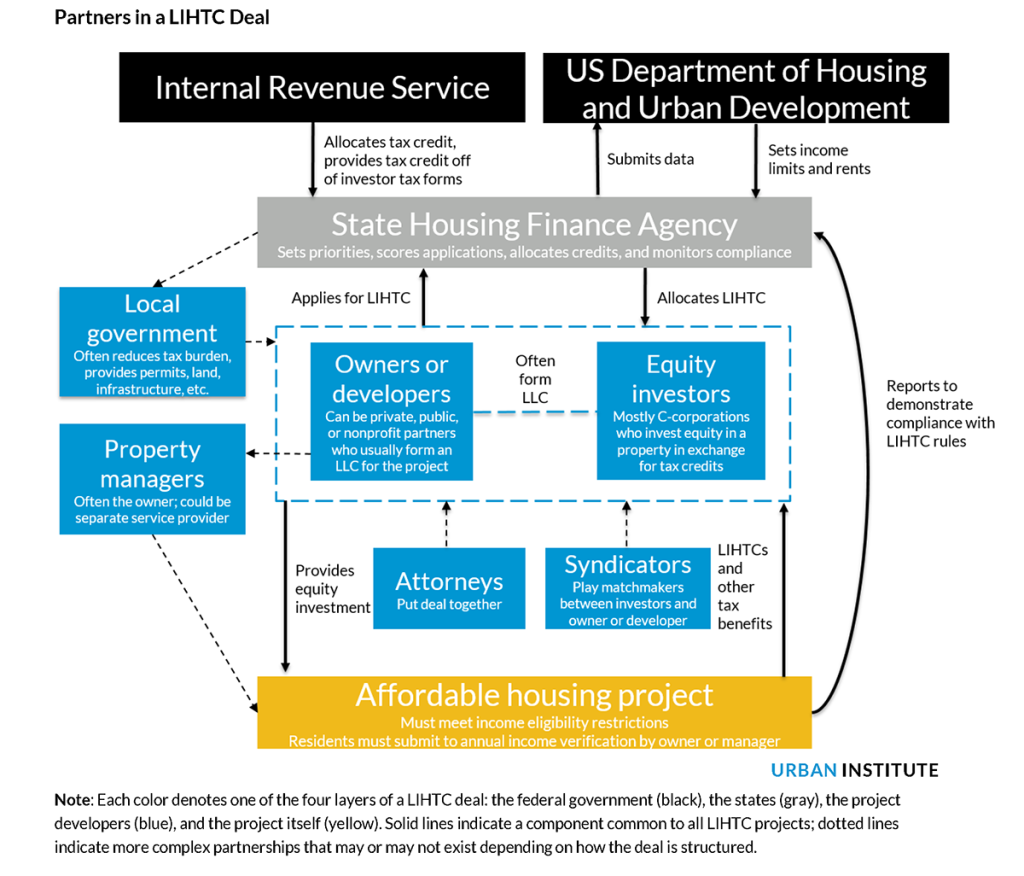

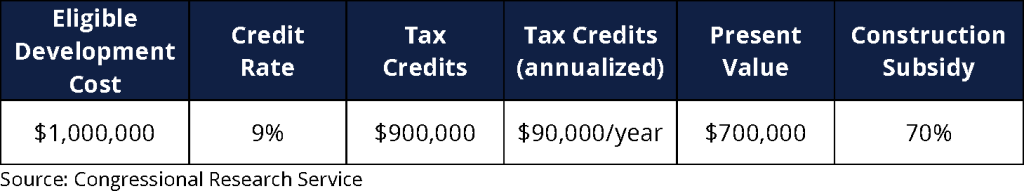

The distribution of Low-Income Housing Tax Credits (LIHTC) profoundly affects the financing of affordable housing. The federal government allocates these credits to states, which in turn award the credits to institutions concerned with the development of affordable housing, including private developers. Typically, state housing finance agencies allocate tax credits to developers, who exchange or sell the credits to investors. According to the Congressional Research Service, an investor might purchase a $1 tax credit for $.80 or $.90, providing capital to the developer, and a marginal tax reduction for the investor. Funds from purchasing the tax credits are used to construct the development, and equity investors benefit by reducing their tax liabilities. For a new development, up to 70 percent of the cost of affordable housing construction can be covered using LIHTCs, allowing the units to be offered at well below market rate. See Table 3 below. For more information on the intricacies of LIHTCs, a complex corner of housing finance, see The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit: How It Works and Who It Serves by the Urban Institute.

Partners in a Low-Income Housing Tax Credit Deal. Source: Scally, Gold, and DuBois. (2018). The Low-Income Housing Tax Credit: How It Works and Who It Serves. Urban Institute.

Table 3. Low Income Housing Tax Credit Example

Often, stacking LIHTCs with other housing funds, such as Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) or state funds such as those from the New Jersey HMFA, adds complexity to the process. In the case of the all-affordable TOD Station at Grant Avenue in Plainfield, financing included LIHTCs at a four percent rate as well as $15.3 million in CDBG Disaster Recovery funding. CDBG Disaster Recovery funding assists low-income areas when recovering from Presidentially-declared disasters—in this case, Superstorm Sandy. The building, which opened in March, features 90 units that are reserved for those with incomes between 30 and 60 percent AMI. As the cost to renovate or construct an affordable apartment is the same as a market-rate one, funding stacks subsidize development costs, which enables the developers to offer the units at a far lower cost to renters.

When traditional funding sources fall short of covering all costs, affordable housing developers can look for gap financing, or alternate streams to complete the capital stack and ensure the project is constructed. In New Jersey, two programs, the Department of Community Affairs’ (DCA) Affordable Housing Trust Fund, and HMFA’s Special Needs Housing Trust Fund, award gap financing to applicants to help create affordable units for the state’s most vulnerable residents.

TOD Finance Moving Forward

As eTOD becomes a priority for activists, transit agencies, and government bodies, attention must be paid to the creation of equity requirements that consider the intricacies of development finance, namely, for gap financing that would enable the actual construction of affordable housing. As one affordable housing developer shared, a lack of understanding from politicians and community advocates often muddied the conversation. In the example from Seattle shared at the outset of this article, the nuances of 60 percent and 80 percent AMI may have rendered a well-meaning density bonus provision ineffectual.

Transit areas provide ideal locations for affordable housing, relieving lower-income households of personal vehicle expenses. However, in practice, the presence of affordable housing in transit areas may be limited, in both New Jersey and the nation at large. Without minimum requirements, and readily available gap financing, developers may see little incentive to add affordable units, ultimately building TODs with units at only market or luxury rates. While economists and housing researchers are currently debating the merits of merely adding market rate units to relieve pressure on existing affordable housing, the growing severity of today’s housing crisis necessitates action on all fronts. This is where TOD, as a denser, more sustainable form of urban growth, provides a strategic opportunity to create more housing.

With a clear grasp of development finance, it becomes easier to understand the financial operating philosophies of developers, non-profits, government actors, and transit agencies, as well as the underlying economics of affordable housing. With this knowledge, communities and policy makers can devise better planning and public policy solutions to achieve their goals, and imagine and implement more effective incentives and statutory requirements to improve the next generation of TOD.

Special thanks to Lorraine Wilson-Drake, Patrick Terborg, and Bree Jones for their valuable expertise that contributed to this article.