Design concept for Bliss Avenue in Pittsburg, CA. Pedestrian friendly streetscape, mid-block pedestrian crossings, and mixed-use buildings.

Get moving. That’s what the health experts tell us. Want to be healthier and happier? Be active. Walk. Get out of your car. Good advice, but for many Americans, that’s easier said than done.

Making it easier to be physically active can be beneficial to individuals and communities alike. Changes to transportation systems can help make an active lifestyle easier. It is increasingly evident that a landscape dominated by the car, cul-de-sacs, and multi-lane roads that are hard for pedestrians and bicyclists to navigate is associated with higher levels of obesity, respiratory diseases such as asthma, and stress. National health care costs were roughly $2.7 trillion in 2011,[1] with obesity and obesity-related illnesses growing to about $147 billion.[2] Exercise can help keep the rising costs down by lowering obesity rates and the prevalence of associated diseases. Thus, a built environment that offers transit, walking, and bicycling options improves the health of individuals and their community.

Transit-oriented development (TOD) gives people a wider range of housing choices and more transportation options beyond the car. Proximity to multimodal transit means that people are more likely to leave their cars at home and walk or bike to the bus stop or train station, and urban design is essential to enabling residents to do so. While density is crucial, the infrastructure near a TOD must be designed to meet people’s needs, by including sidewalks and other pedestrian connections, bicycle lanes, narrower road widths to slow traffic, and smaller intersections to decrease crossing distances. This “smart” infrastructure is vital for connecting destinations so that people can easily walk or bike from one place to another, regardless of age or physical ability.[3] Street connectivity, the theme of our Summer 2011 issue, creates shorter trips, thus eliminating a major reason people choose cars over walking or biking.[4]

But the health benefits from the combination of TOD, transit, and smart infrastructure through the activity they promote extend far beyond weight management. TOD offers the potential for safer streets and cleaner neighborhoods. As people walk and bike around town and take public transit instead of driving, fewer cars are on the road. Not only are traffic fatalities and accidents reduced, air pollution decreases as do rates of respiratory illnesses such as asthma.[5]

While advocates of TOD have implicitly referenced the health benefits of TOD, new planning and development tools, such as Health Impact Assessments (HIAs), help make the link between TOD and good health explicit. Two recent examples of HIAs evaluate the health impacts of transportation projects in California and in Oregon.

Pittsburg, CA

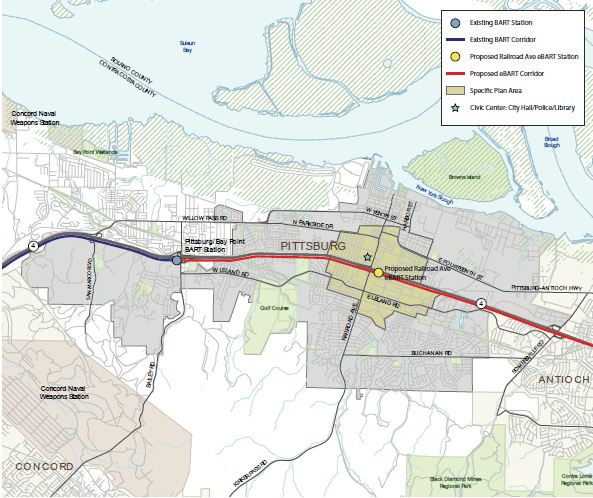

Pittsburg, California is a San Francisco suburb with a population of 57,000. Pittsburg’s population is younger than most municipalities in the region, and attracts white-collar workers seeking affordable housing. Over the next twenty years, it is projected to grow by 15%, far more than its county’s average. To help absorb the anticipated demand for housing and businesses, the city is contracting developers to build a TOD surrounding the new BART train station adjacent to State Route 4. This TOD, the Railroad Avenue Specific Plan, will include housing, office and retail space, and parking as well as bicycle and pedestrian infrastructure to enable residents to walk and bike to and from the train station. In 2008, the city commissioned the California-based organization Human Impact Partners to complete an HIA for the project. Recommendations offered in the HIA suggested health policies in a number of areas including housing, livelihood (or employment), transportation, and area retail, as well as practices to improve project air quality and to reduce community noise impacts. Many of the policy recommendations are crosscutting—ostensibly acting in one policy area but affecting several. For example, parking restrictions, whether a reduction in structured parking for residential uses, unbundling parking costs from housing, or free parking for car sharing, has the collective effect of reducing driving, lowering air pollution impacts, improving housing affordability, and promoting active transport. Equally important is the recommendation for comprehensive on-site retail so as to minimize the need to travel to distant locations and to allow residents to satisfy their daily needs without a personal vehicle. Another significant set of recommendations is for comprehensive bicycling and pedestrian planning and the improvement of facilities throughout the proposed project, including secure bike parking at the station—again, supporting active transportation, reducing air pollution impacts, and reducing injury caused by bicycle-vehicle conflicts. These are but a few ways in which the HIA assessed the potential impact of new development and provided recommendations that both directly and indirectly impact health.[6]

Portland, OR

In 2010, the Oregon Public Health Institute and Portland Metro completed an HIA for the proposed Lake Oswego to Portland Transit Project, a corridor that contains about 13,000 people. In an area that has little room to expand its roads, the Portland-Lake Oswego transit line will help accommodate the increasing travel demand between Lake Oswego and Portland by encouraging dense development around its stations. The HIA assessed the impact of three potential project scenarios: a no-build, an enhanced bus service, and a streetcar. The report found that the streetcar option would have the highest ridership and provide the most potential health benefits; in 2011, it was recommended as the Locally Preferred Alternative over the no-build scenario. The streetcar line would increase transit weekday ridership on the corridor by more than 4,000, while significantly decreasing annual vehicle miles by about 1,000,000. With fewer cars on the road, walking and bicycling will be safer, and emissions of toxins from automobiles are expected to decrease by 3.8%. After the transit line is built, the HIA authors will reevaluate the influence the HIA had on the project.[7]

Both HIAs have been helpful tools for addressing issues related to transit and development that would have remained undocumented by traditional planning methods. Many potential health issues can be brought to light and addressed through an HIA, the very health issues that TOD advocates are concerned with: noise pollution, lack of pedestrian infrastructure, and lack of affordable housing. In this sense, HIAs are an ideal tool for planners wishing to measure the health impacts of TODs and to increase awareness of and support for transit-oriented development by implementing its recommendations.

HIAs hold promise for New Jersey’s TOD communities. This new tool can allow communities to more readily understand the impacts of the development and transportation decisions they face and to better assess the choices available to them.

References

[1] United States. 2010. Table 130. National Health Expenditures – Sumary, 1960 to 2008, and Projections, 2009 to 2019. Statistical Abstract of the United States, 2011. Washington, DC: U.S. Census Bureau. Link

[2] Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2011. Overweight and Obesity: Economic Consequences. Link

[3] Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. 2009. Designing for Active Living Among Adults. Research Summary. Link

[4] de Nazelle, Audrey et al. 2011. “Improving health through policies that promote active travel: A review of evidence to support integrated health impact assessment.” Environment International. 37(4): 766-777. Link

[5] Makekafzili, Shireen. 2009. Healthy, equitable transportation policy recommendations and research. Oakland, Calif: PolicyLink. Link

[6] Human Impact Partners. 2008. Pittsburg Railroad Avenue Specific Plan Health Impact Assessment. Link

[7] Oregon Public Health Institute. 2010. Lake Oswego to Portland Transit Project: Health Impact Assessment. Link