Introduction

Much of the country faces a housing crisis, driven by decades of underproduction and a growing number of households. New Jersey is no exception. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, the state has a shortage of nearly 215,000 units for extremely low-income renters alone. The gap between the housing supply and demand continues to grow, placing additional pressure on affordability and availability.

In response, some states have turned to proactive zoning reforms to address the crisis. In Washington State, for example, cities with populations over 75,000 must now allow at least four homes on all lots. California, Oregon, and Vermont have also enacted provisions to encourage housing development by reforming restrictive local zoning laws.

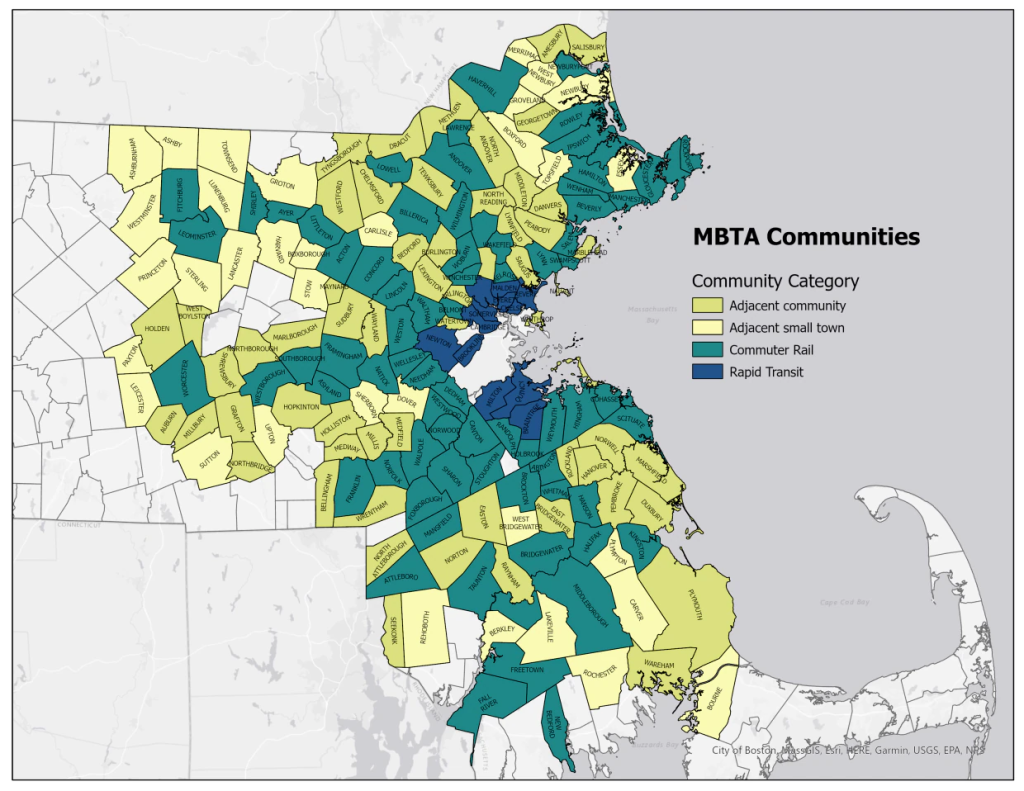

Massachusetts offers an interesting case study in what Suffolk University Law Professor John Infranca describes as “a modest intervention in local zoning and one that retains significant local control.” In 2021, the state enacted the MBTA Communities Law, which requires municipalities served by the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) to create zoning districts that permit multifamily housing near transit. Unlike more sweeping state-led rezoning efforts, Massachusetts’s approach allows each city and town to determine how to comply with the law’s requirements while ensuring that land near transit is available for housing.

As New Jersey and other states consider strategies to address their own housing affordability challenges, Massachusetts’s experience with the MBTA Communities Law may provide valuable lessons. The different ways municipalities have approached implementation offer insights into how statewide zoning reform can be structured to promote housing growth while maintaining local decision-making authority.

Massachusetts, like the rest of the country, remains in the grip of a housing shortage. Decades of restrictive zoning, downzoning, and suburban-style subdivision development have severely limited the production of homes that are affordable to low- and moderate-income households—particularly in areas near public transportation. As the 2024 Greater Boston Report Card notes: “The shortage of adequate housing is at the heart of many of Greater Boston’s housing challenges.” By examining Massachusetts’s approach, policymakers elsewhere may find a framework for balancing state-led zoning reform with local governance to expand affordable housing opportunities near transit.

Background

Prior to the passage of MBTA Communities Law, population density near transit facilities, particularly commuter rail stops, remained low. Zoned Out, a 2020 Brookings Institution report, found that the median density at MBTA commuter rail stations was just 2.8 units per acre. Most towns prohibited new multifamily construction near transit facilities.

In 2021, Massachusetts passed the MBTA Communities Law to address the state’s growing housing affordability concerns. The law required municipalities with access to rapid transit or commuter rail to establish at least one zoning district near transit that permits multifamily housing development.

The law was part of the broader $626 million economic development bill, H.5250. An Act for Enabling Partnerships for Growth, which aimed to support recovery from the COVID-19 pandemic. In addition to funding grant programs, the bill included two key provisions related to zoning: reducing the threshold to adopt multifamily zoning changes from a two-thirds vote to a simple majority, and mandating that municipalities with MBTA service create zoning districts for multifamily housing near transit. To support these efforts, the bill also allocated $50 million for transit-oriented housing projects.

Implementation and Compliance

Lawmakers designed the MBTA Communities Law using a tiered approach: each city or town, based on its proximity to different types of transit, must zone a minimum area for multifamily housing. The law minimizes barriers to development—new housing in these zones cannot require special permits, and zoning must allow at least 15 units per acre. Environmentally sensitive and publicly owned parcels, such as wetlands and municipal buildings, are excluded from the designated districts.

To assess whether each zoning district meets the law’s requirements, the Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (EOHLC)—the state’s housing agency—developed a GIS- and Excel-based model. Municipalities must submit their zoning proposals, along with the model and calculations, to ensure compliance.

Since the law’s passage, December 31 has served as a key deadline for municipalities to adopt their required zoning. The timeline follows a phased approach, starting with the most transit-accessible communities and gradually expanding outward.

- Rapid transit communities in the Boston urban core had to comply by December 31, 2023.

- Commuter rail communities had to meet the requirements by December 31, 2024.

- Adjacent communities—those bordering towns with commuter rail stations—face a December 31, 2025, deadline.

- By December 31, 2026, small towns adjacent to transit-served communities must adopt their multifamily zoning.

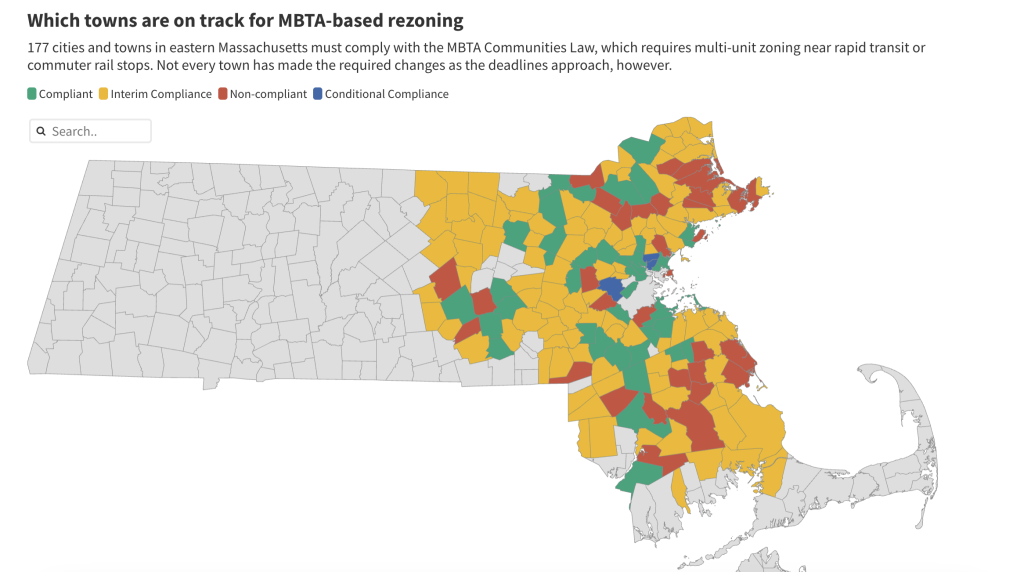

Most municipalities have responded positively to the law. By February 2025, 147 of the 177 affected communities had successfully adopted multifamily zoning—an achievement that has created capacity for thousands of new transit-friendly homes in areas where multifamily housing was previously prohibited.

Still, some towns remain resistant. The Town of Milton, a rapid transit community bordering Boston, became the first to reject the law outright. In early 2024, 54 percent of voters opposed a special referendum to establish a multifamily district near the town’s trolley station. As a result, Milton lost access to state grants, including $140,000 earmarked for seawall construction. After Milton’s continued incompliance, the Massachusetts Attorney General chose to sue the town. In January 2025 the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court ruled in favor of the Attorney General, allowing the state to enforce the law. Milton then had a February 13 deadline to submit an action plan outlining the path for compliance, however, the town voted against submitting a plan, leaving the state to decide what must happen next.

Even as legal challenges unfold, municipalities across Greater Boston continue adopting multifamily zoning, taking diverse approaches to compliance. The following section examines case studies of different MBTA communities, highlighting their strategies and offering insights for potential policy consideration in New Jersey.

Case Studies in Compliance

Rapid Transit Community: Somerville, Massachusetts

Distance to Boston: 3 miles

Minimum Multifamily Unit Capacity: 9,067 homes

Somerville, a city of 81,000 bordering Boston to the northwest, is one of the most densely settled municipalities in New England. Once a streetcar suburb, it remains largely composed of two and three-family homes, known locally as “triple deckers,” many of which were historically nonconforming under the City’s zoning code.

While many municipalities responded to the MBTA Communities Law by designing multifamily zoning overlays near their transit stations, Somerville took a different approach. With a minor adjustment to its form-based zoning code, the City permitted three-family homes “by right”—without requiring special permits—across all residential neighborhoods. In effect, Somerville became one large MBTA zoning district.

However, one critique of this streamlined solution is that it does not encourage denser forms of housing. Despite benefiting from the completion of a multibillion-dollar light rail extension in 2022, Somerville has yet to meaningfully upzone most station areas for mixed-use infill development. While the City met the letter of the MBTA Communities Law, it arguably fell short of its spirit by not maximizing housing production near high-frequency transit.

Somerville’s case illustrates both the strengths and limitations of the MBTA Communities Law. While it nudges municipalities toward more flexible zoning, it does not necessarily guarantee the level of density needed to fully address the region’s housing shortage. As a first step, the law broadens zoning capacity for housing, but further state-level efforts may be needed to ensure robust housing production near transit.

Commuter Rail Community: Wellesley, Massachusetts

Distance to Boston: 13 miles

Minimum Multifamily Unit Capacity: 1,392 homes

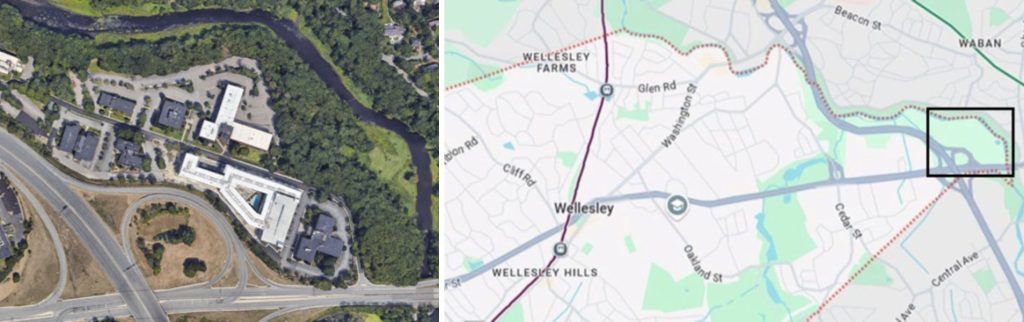

The Town of Wellesley exemplifies the balance municipalities can strike between meaningful zoning reform and “paper compliance.” One tactic Wellesley employed to limit new housing production was designating multifamily zoning districts over recently constructed developments. By doing so, the Town technically met its zoning requirements while ensuring that near-term development potential remained minimal.

Wellesley met more than half of its 1,932-unit capacity requirement by including a large, recently built multifamily development on the town’s outskirts in its count. While technically within walking distance of a light rail station, the connection between the development and the station can only be made via a circuitous route. This approach—meeting the letter of the law while minimizing new transit-oriented housing—provides a clear example of paper compliance.

However, not all of Wellesley’s zoning changes were so limited in impact. The Town also made meaningful modifications in two key commercial centers, Wellesley Square and Wellesley Hills, both served by commuter rail. Here, Wellesley allowed by-right development and increased allowable density to 17 units per acre. Unlike with the paper compliance district, these changes create genuine opportunities for new housing near transit.

Wellesley’s approach highlights the significant flexibility built into the MBTA Communities Law. Municipalities have wide latitude in determining how they comply—whether through strategic zoning changes that facilitate housing production or through technical maneuvers that limit actual development.

Adjacent Community: Lexington, Massachusetts

Distance to Boston: 12 miles

Minimum Multifamily Unit Capacity: 1,231 Homes

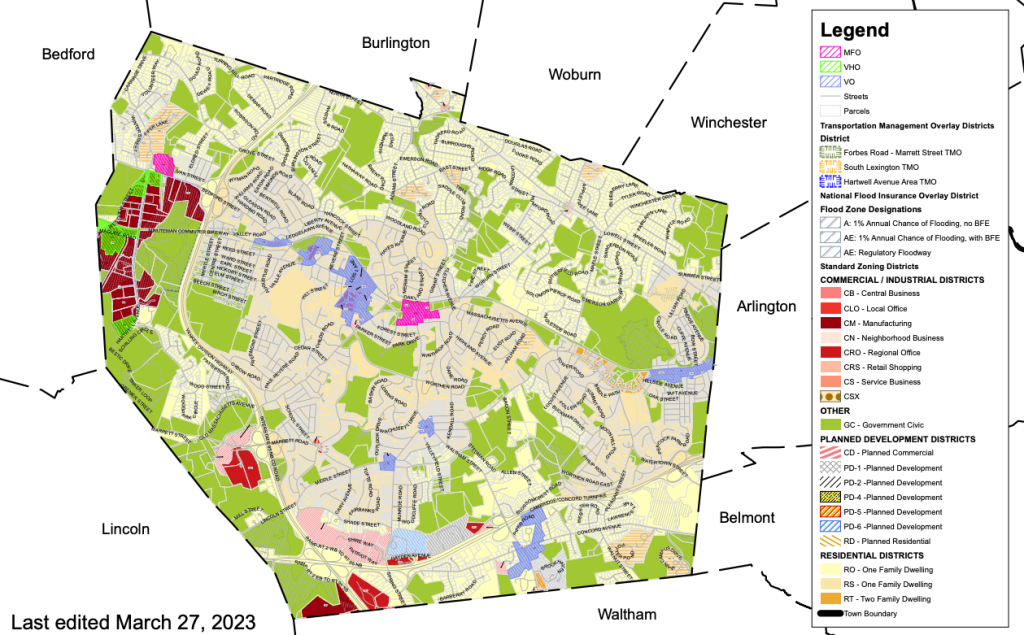

Lexington’s MBTA Communities Law compliance has been widely hailed as a success of the initiative. Although not directly served by commuter rail, the Town was one of the first to adopt MBTA zoning in 2023, well ahead of the December 2024 deadline for designated Adjacent Communities.

For its compliance, Lexington opted to create twelve new overlay districts across 227 acres in town—nearly four times the land area required by the state. The Town drew its districts primarily along the Minuteman Commuter Bikeway, a former railway that was converted to a bicycle route in the 1990s. In addition to local bus service, new residents of development adjacent to the bikeway would be able to ride the corridor several miles to Alewife Station, where they could board for subway service into Boston.

In the year since the adoption of the new zoning, Lexington reports eight new multifamily housing projects in the planning pipeline, ranging in size from a 30-unit condo building to a 312-unit rental apartment complex. According to the Boston Globe, if all are constructed, Lexington would add more than 1,000 homes to its housing stock, with 15 percent reserved as affordable units. This scale of development, with this level of affordability, in this community, would have been unthinkable before the passage of the MBTA Communities Law.

Why has Lexington’s MBTA zoning been such a success? Some point to a contentious 1971 referendum that blocked subsidized housing in the town, which may have motivated local voters to rectify it in some fashion. High housing costs—the median home sold for $1.7 million in 2024—and the resulting lack of inventory for the children and family members of existing residents, municipal employees, and low and moderate-income households may have also motivated the large-scale change.

In sharp contrast to Wellesley, Lexington chose to meet not just the letter but also the spirit of the MBTA Communities Law—and is already seeing results.

Adjacent Small Town: Newbury, Massachusetts

Distance to Boston: 40 Miles

Minimum Multifamily Unit Capacity: 154 Homes

Some smaller municipalities near—but not served by—commuter rail have been designated as Adjacent Small Towns. These towns have fewer than 100 acres of developable area (as determined by the state housing department’s model) and either fewer than 7,000 residents or a population density below 500 people per square mile. To account for their limited capacity, Adjacent Small Towns receive a smaller multifamily zoning requirement.

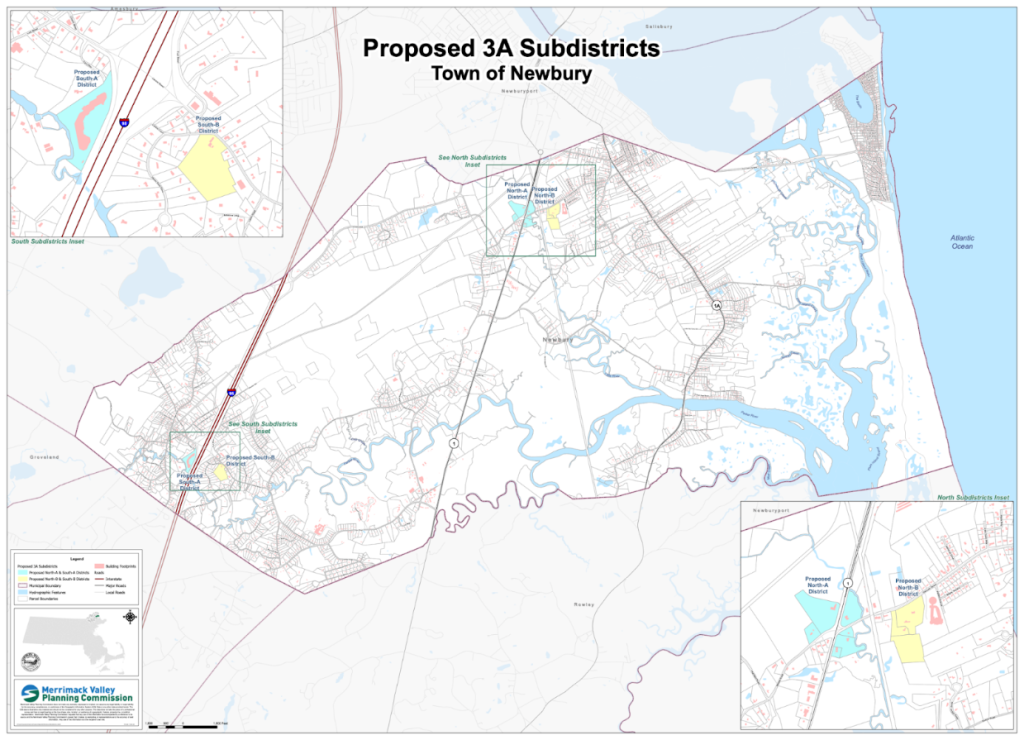

For example, Newbury, located north of Boston near the New Hampshire border, must zone for at least 154 new homes. Like Wellesley and Lexington, Newbury adopted a diversified strategy, establishing multiple zoning subdistricts across town. Ten percent of all future units in these subdistricts will be dedicated as affordable housing. Given flexibility in drafting its multifamily zoning, the Town pursed a mixed approach, with some parcels meeting compliance on paper and others holding real potential for new housing.

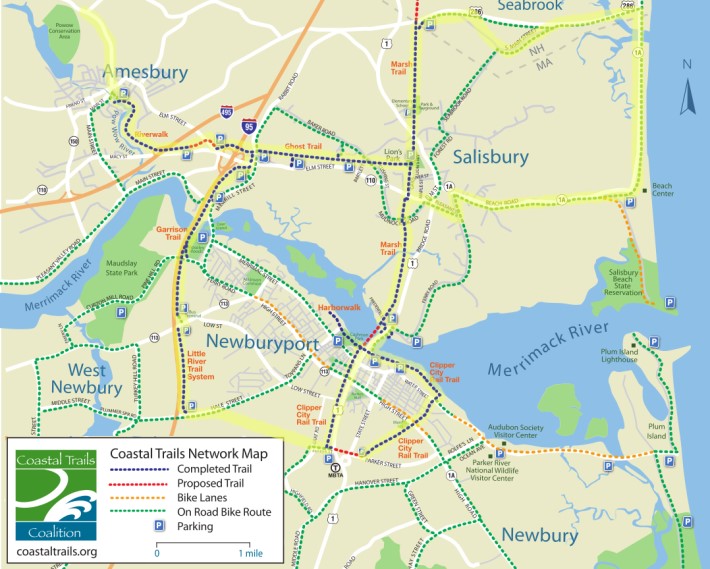

Some subdistricts appear to meet only the minimum zoning requirements. One includes a busy strip mall across from Interstate 95, while another consists largely of wetlands. However, other areas offer stronger prospects for development. A cluster of parcels near the town’s northern border is close to the Newburyport MBTA station, and a planned bike path connection could enable future residents to commute by bike and train.

Even in this small town of 6,000 residents, located 40 miles from Boston, incremental progress is underway. Newbury is expanding opportunities for people to live in the region and access jobs and education by making space for new housing- including affordable homes.

Key Considerations

What lessons from Massachusetts’s MBTA Communities Law might be most useful for New Jersey-based planners and policymakers? Beyond the clear progress made by numerous municipalities zoning for multifamily housing near transit stations, several additional considerations stand out:

Carrots and Sticks

Municipalities often cite new infrastructure and service costs as reasons to oppose housing development. While research has dispelled many myths about housing production, tying state grants for water and wastewater improvements, schools, and transportation infrastructure to multifamily zoning requirements could be an effective approach.

The MBTA Communities Law does not directly fund compliant cities and towns but excludes non-compliant communities from certain state grants. Additionally, the recently launched MBTA Communities Catalyst fund provides $15 million for projects related to housing development, infrastructure upgrades, and property acquisition to support housing growth.

Preventing Paper Compliance

To ensure zoning changes lead to actual housing production, policies should limit opportunities for paper compliance. One strategy would be to exclude land with structures built within the past ten years from counting toward zoning requirements. This approach would have discouraged Wellesley from counting recently built housing units in its allocation and might have incentivized additional upzoning near commuter rail stations.

Draft Model Zoning

A state model zoning bylaw, rigorously vetted for effectiveness, could help ensure meaningful multifamily housing production. While the MBTA Communities Law prohibits certain restrictions (such as requiring a discretionary special permit), municipalities can still introduce regulations that—whether deliberately or unintentionally—hinder development.

A state model zoning code, reviewed by developers and architects, could minimize obstacles and reduce compliance delays. It would also lower the technical burden on municipalities, many of which have had to hire consultants or rely on regional planning agencies to meet zoning requirements.

Massachusetts already has a model zoning framework under Chapter 40R “Smart Growth” zoning, which promotes multifamily development near transit and downtowns through financial incentives. Adapting this existing program for MBTA Communities might have streamlined the process and enhanced participation.

Coordinate with Transit Agencies

Ironically, when Massachusetts enacted the MBTA Communities Law, the legislature largely moved forward without input from the state’s largest transit agency. The MBTA is barely mentioned in the legislation, despite transit agencies playing a critical role in transit-oriented development.

Transit agencies bring valuable expertise in:

- Ensuring new development does not create operational challenges,

- Managing station access for new residents, and

- Planning for potential ridership increases.

As landowners, transit agencies may also hold key parcels for potential development. A stronger statewide TOD policy could facilitate collaboration on how to best utilize these assets. Massachusetts missed this opportunity by leaving the MBTA out of the conversation.

The Bottom Line

The MBTA Communities Law has the potential to reshape housing development in the Boston metropolitan region. While its full impact may take years to unfold, developers are already advancing new transit-friendly housing proposals.

For decades, Massachusetts struggled to incentivize multifamily development near transit. Now, this initiative promises significant progress in advancing smart growth and housing affordability. Challenges remain in promoting affordability, equity, and transit-oriented planning, but MBTA Communities represents a meaningful step forward—one from which other states can learn.

A special thanks to Noah Harper for his work in putting this article together.

Resources

2024 Greater Boston Housing Report Card | The Boston Foundation

Bill H.5250: An Act Enabling Partnerships for Growth | Massachusetts Legislature

California Gov. Signs Landmark Duplex and Lot-Split Legislation | HK Law

Chapter 40R | Massachusetts

Density Bonus Payment Application | Massachusetts

Eliminating Single-Family Zoning and Parking Minimums in Oregon | Bipartisan Policy Center

Guest Post: A Survey of Ambitious State Policies from Across the Country | Boston Indicators

In Lexington, The State’s Housing Law Is on Track to Produce Nearly 1,000 New Homes | Boston Globe

Lexington: Local Market Update | Massachusetts Association of Realtors

MBTA Communities Catalyst Fund | Massachusetts

Milton Continues to Push Back on MBTA Zoning Law | NBC Boston

More Than 100 MBTA Communities Have Approved Multifamily Districts to Create More Housing, Lower Costs | Massachusetts

Multi-Family Zoning Requirement for MBTA Communities | Massachusetts

New Jersey: Housing Needs by State | National Low Income Housing Coalition

Vermont Adopts Historic Housing Reform | CNU Public Square

WA Senate Passes Bill Allowing Duplexes, Fourplexes in Single-Family Zones | Seattle Times