Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) is gaining prominence for new transit investments in the United States and abroad. Able to deliver levels of service similar to light rail at a lower cost, frequent BRT service is planned for Nashville, Minneapolis, Jacksonville, Austin, and many more cities across the country. At the same time, transit-oriented development is becoming a standard component to any transit expansion. BTOD (Bus Transit-Oriented Development) is a subsection of transit-oriented development, defined by transit mode, which is similar, but not identical, to more predominant rail-based development. By looking at three examples of BTOD in Cleveland, Pittsburgh, and Denver, we can find applicable lessons from their successes and challenges. These existing BTOD practices provide insight for transportation and land use planners to foster vibrant, equitable transit-oriented development alongside frequent bus service in their cities and regions.

Cleveland

Cleveland’s HealthLine is an exemplary model for American Bus Rapid Transit. Extending along Euclid Avenue, the HealthLine connects downtown Cleveland with medical services at the Cleveland Clinic, the Cleveland Museum of Art, and knowledge centers, such as Cleveland State University and Case Western Reserve University. Launched in 2008, the 6.8-mile corridor now accounts for nearly ten percent of the Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority’s (RTA) annual ridership. On the tenth anniversary of the rapid transit route, RTA noted that the HealthLine has contributed to $9.5 billion in economic development along the corridor, including hotels, office space, and 8,800 new residential units.

As one of the oldest BRT systems in the country, the HealthLine provides valuable lessons for how TOD can flourish along a rapid bus route. The width of Euclid Avenue allowed for a dedicated lane to be easily installed for almost the entire length of the trip, from downtown Cleveland to Stokes-Windermere Station. At its eastern terminus, the HealthLine connects with the heavy rail Red Line—an existing rapid transit route that runs parallel to some of the HealthLine route, but is situated too far from many destinations, such as the Cleveland Clinic or Cleveland State University, to provide pedestrian access.

It is the nature of the Euclid Corridor—its multiple hospitals, art museums, educational institutions, performance venues, and varied job centers—which has helped it to flourish. In Trains, Buses, People: An Opinionated Atlas of US Transit (2020), the engineer and Rice University urban planning professor Christof Spieler writes that “Successful transit systems work because they serve places where many people want to go: commuting destinations like employment centers and universities; gathering places like sports stadiums, convention centers, and entertainment districts; and dense, walkable, mixed-use neighborhoods.” On Euclid Avenue, many of these uses already existed, but lacked reliable connectivity.

The clustering of anchor institutions makes intuitive sense from a historic point of view—at the turn of the century, streetcars carried passengers along Euclid Avenue. Indeed, University Circle, where a new contemporary art museum and block-length mixed-use developments have redefined the district, was named for its streetcar turnabout. In this way, the HealthLine can be seen as reconnecting an area once linked by an earlier form of transit. With anchor institutions once again within reach, the new rapid service has spurred billions in infill development and new institutional investments. By drawing a line between in-demand destinations, and providing frequent service between them, Cleveland’s first BRT corridor provides an ideal case study for BTOD.

The system itself is consistent. Covered shelters are found at each of the 36 stations, with ticket machines and level curbs for quick, precise boarding. Dedicated bus lanes run from downtown Cleveland, through the Midtown and University Circle neighborhoods, before converging with the Red Line heavy rail station. Persons wishing to visit the downtown Theater District, the Cleveland Clinic, or connect to the airport will find themselves conveniently served by the HealthLine, day or night. According to the BRT line’s engineering firm, ridership of the upgraded service has increased by 54 percent. The consistent, quality upgrades that the HealthLine brought have been recognized by both riders and developers.

Ten years after the advent of the nation’s premiere BRT route, RTA estimated, based upon figures from community development organizations, that the agency’s $200 million investment had propelled $9.5 billion in development along Euclid Avenue. This development included new learning centers, such as Case Western Reserve’s Health Education Campus, multiple innovation hubs, apartment and townhouse developments, traditional office space, and more. Development has continued, particularly in the University Circle neighborhood, with several mixed-use high-rises planned to begin construction in March 2022. Another planned project is an “Innovation Community” in the Midtown neighborhood, a collaborative project of the City, the Cleveland Foundation, and the MidTown Cleveland community development organization. Investments, spurred by the HealthLine’s presence, are ongoing.

RTA has built on the success of the HealthLine by investing in new frequent bus services, such as the MetroHealth and Cleveland State Lines, which provide service every 15 minutes or better during rush hours to the south and west of Cleveland. RTA also recently rolled out its NEXT GEN RTA bus service redesign, which prioritizes frequent service over coverage to better connect bus users. These moves have established new rapid transit corridors and improved conditions for future TOD. Euclid Avenue’s HealthLine, with reliable service between established cores, remains a model for BTOD for both Cleveland and the rest of the country.

Pittsburgh

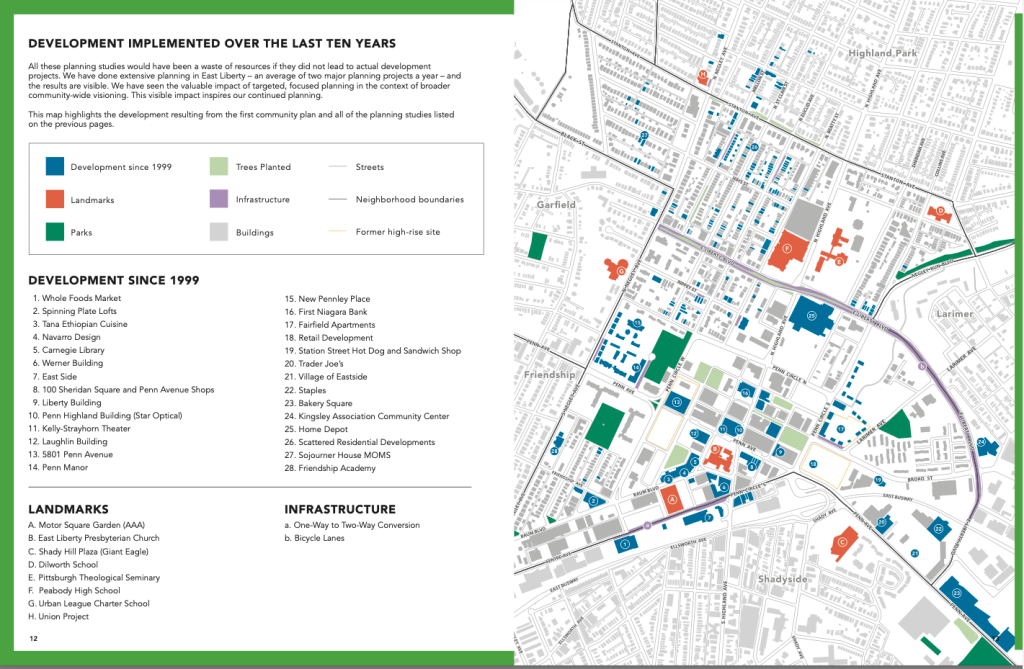

Pittsburgh’s Martin Luther King Jr. East Busway is one of the oldest in the country, having opened in 1983. The route, one of three current BRT corridors in the region, runs east from downtown Pittsburgh, and terminates at Swissvale. About halfway between each destination, the P1 and P2 buses stop at the East Liberty Station, which serves a historically-disinvested area known for its high-rise public housing towers. Redevelopment efforts for the neighborhood began in the late 1990s, and, according to a 2013 analysis by the Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP), $903 million in development investments have been made in the area since. While successful in transforming the East Liberty Station, the dramatic change provides a lesson for planners that equity must be considered during revitalization efforts.

East Liberty’s revitalization was the product of a collaborative effort between nonprofit community development corporation East Liberty Development Incorporated (ELDI), the City of Pittsburgh, the local Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), and the national nonprofit Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC). Historically, the neighborhood was known as Pittsburgh’s “second downtown,” though East Liberty declined in the second part of the twentieth century with the rise of car-oriented suburbanization. A highway, known as Penn Circle, cut through the neighborhood, and several 200-unit high-rise apartment complexes became HUD-subsidized housing as higher-earners relocated from the area.

Bordering the southern part of the neighborhood is the MLK Jr. East Busway, providing quick connections to downtown Pittsburgh. While for the first three decades redevelopment efforts in East Liberty did not explicitly consider the busway, it remained an infrastructure asset to the community, enabling denser, more pedestrian-oriented development.

However, East Liberty’s renaissance began with the opening of a Home Depot. As related in the ITDP report More Development for Your Transit Dollar, ELDI’s goal was to demonstrate the economic vitality of the area, to use the retailer’s presence as a sign of transformation. The City of Pittsburgh purchased a disused lot, formerly a Sears department store, and began pursuing Home Depot as an anchor tenant. Then-Mayor Tom Murphy asked the store’s co-founder Bernard Marcus to visit the site, and was able to persuade him to put a store there. Fifty-three percent of the retailer’s development costs were covered by the City through the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA), using the revolving Pittsburgh Development Fund (PDF), and a newly-created Transit Revitalization Investment District (TRID), a Pennsylvanian version of Tax Increment Financing (TIF). With these two funding sources, the Home Depot opened in 2000.

Simultaneously, the City of Pittsburgh conducted a market research study of the neighborhood, and commenced a comprehensive planning effort in collaboration with ELDI. A private developer, the Mosites Company, became interested in constructing a Whole Foods as another anchor tenant in East Liberty. This project was financed with funds from the URA, private debt, a loan from the Local Initiatives Support Corporation (LISC), and a grant from the US Department of Health and Human Services. East Liberty’s revitalization advocates credit the Whole Foods with catalyzing the neighborhood’s transformation.

A final anchor, the Bakery Square development, to the south of the Busway, was constructed by another private developer, Walnut Capital. Bakery Square, located on the site of a former Nabisco factory, was financed through Historic Preservation Tax Credits, tax exemption from Pennsylvania’s Building PA program, and Tax Increment Financing from the URA. In a major success for the area, Google became a chief tenant in Bakery Square.

The methods used to compile gap funding for the Whole Foods project were redeployed to create what was later called the East End Growth Fund. This type of capital stack, consisting of city funds, grants, philanthropy, and private debt, has been used for further redevelopment efforts. With the help of $2.47 million in philanthropic donations, ELDI was able to begin buying and rehabilitating properties in East Liberty, such as dilapidated housing.

The URA purchased the three large HUD-subsidized housing complexes, and contracted with nonprofit affordable housing developer The Community Builders (TCB) to replace them in phases. Existing residents were given vouchers for new affordable units in the area, and, by 2014, the new affordable housing stock outpaced the old.

For East Liberty Station itself, ELDI studied the use of a Transit Revitalization Investment District (TRID) to help finance a transit-oriented development adjacent to the station, which would include enhancements to the BRT stop as well. This work was financed with the use of TRID-leveraged debt, a Pittsburgh Urban Initiatives New Market Tax Credit (NMTC) allocation, a federal Transportation Investment Generating Economic Recovery (TIGER) grant (now RAISE), nd committed capital from local foundations to guarantee financing.

Adjacent to the busway, the Mosites Company, in a public-private partnership with the URA, has constructed a 360-unit structure which generates $1 million in tax revenue each year. In addition, new pedestrian connections to the station were created, as well as bicycle parking and design improvements, which improved access for neighborhood residents.

Today, East Liberty is a transformed neighborhood with rich urban amenities and sustained growth. The Mellon’s Orchard South Development, by Trek Development Group, is a mixed-income multifamily project, the first phase of which opened in late 2020. For the second phase, a 42-unit apartment building, 70 percent of the units will be priced at or below 60 percent Area Median Income (AMI).

While the busway did not spur redevelopment in East Liberty, it helped to sustain such efforts in the community. More importantly, the collaborative work of government agencies, nonprofits, and private developers helped to revitalize a formerly car-centric district into a bustling transit-oriented community.

Denver Metropolitan Area

In the Denver Metropolitan area, the rollout of the Flatiron Flyer, a Bus Rapid Transit-lite service using express lanes on the US-36 corridor connecting Denver Union Station and Boulder, has received substantial development interest for a BRT route. In Westminster, Broomfield, and Boulder, mixed-use developments have been planned and constructed in coordination with the Regional Transit District’s (RTD) Flatiron Flyer service. For a region experiencing unprecedented housing demand, these developments often struggle to address affordable housing needs. In addition, the ravages of COVID-19 on transit budgets have led to the temporary suspension of two Flatiron Flyer routes, lending credence to the notion that BRT’s perceived impermanence could affect TOD investment.

In contrast with Cleveland and Pittsburgh’s arterial BRT service, the Flyer serves as a regional connector. The service is not technically BRT, as buses mingle with cars for the majority of the trip, though priority lanes, dedicated stations, and frequent service differentiate the Flatiron Flyer from a typical bus service. In addition to the express lanes, the bus may also travel in a specially-widened shoulder in the case of a slowdown in the managed lane. A voter-approved measure for commuter rail service in the corridor passed in 2004, but due to funding pressures, the project has an estimated completion date of 2050. With rail service unlikely to begin for decades, the express bus service from the Flatiron Flyer provides commuter rail-style connectivity for residents along the corridor.

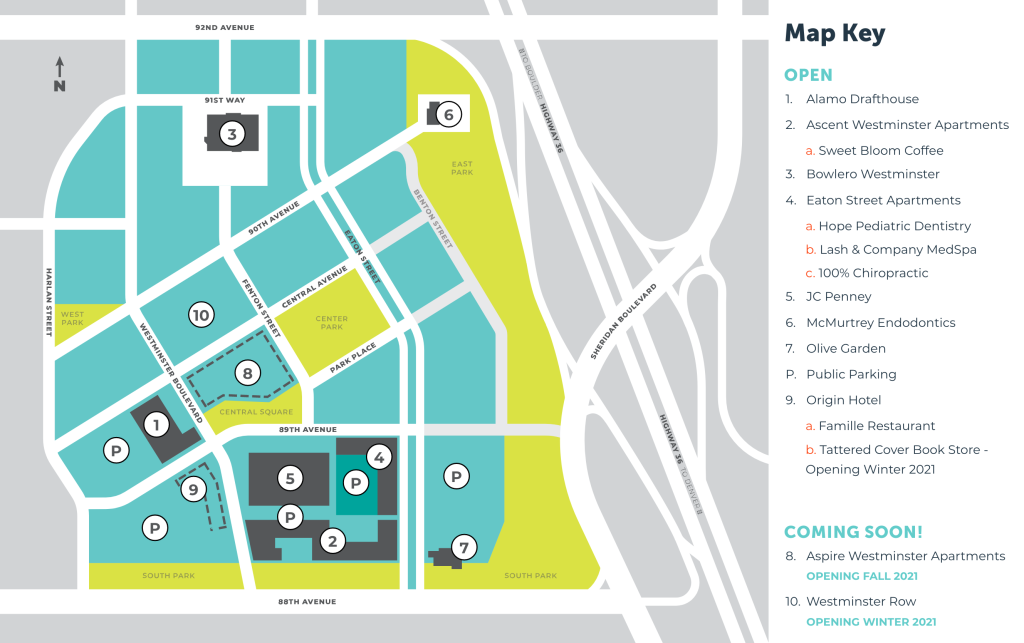

In the City of Westminster, a concerted effort to create a downtown adjacent to the Sheridan BRT stop is underway. Land formerly occupied by a mall has been redeveloped into a walkable, mixed-use center—a space that the suburban municipality has historically lacked. The 255-unit Ascent Westminster opened in 2019, and, next door, the Aspire, a 226-unit development, is set to conclude construction by the end of 2021. Though Westminster has ranked #3 in Colorado for apartment creation, some community activists have expressed concern that the City could do more to promote the creation of affordable units in this transit village. The Ascent and Aspire developments have contributed 26 and 23 affordable housing units, respectively, and, nearby, the Eaton Street apartments added another 118 units of workforce housing.

About five miles up the corridor, nearly equidistant between Boulder and Denver, the Arista Place development in Broomfield is another example of a transit village built along the Flatiron Flyer route. The master-planned town-center-style district features offices, shops and restaurants, apartments, townhomes, and a 7,500 seat event venue. In addition to office space, two medical facilities have opened in the transit village, and UC Hospital Broomfield has purchased an additional 14 acres for a possible expansion. The village is centered around a pedestrian mall that connects to a large pedestrian bridge spanning US-36, allowing for residents to take the Flatiron Flyer to destinations in both directions. Developer Wiens Real Estate Ventures LLC has seen success in the past 15 years of incrementally expanding the transit village, and intends to add more than 800 additional units to the area, bringing the total to 2,000. Crosswinds at Arista, one of the developments in this new phase, would consist of 159 affordable housing units.

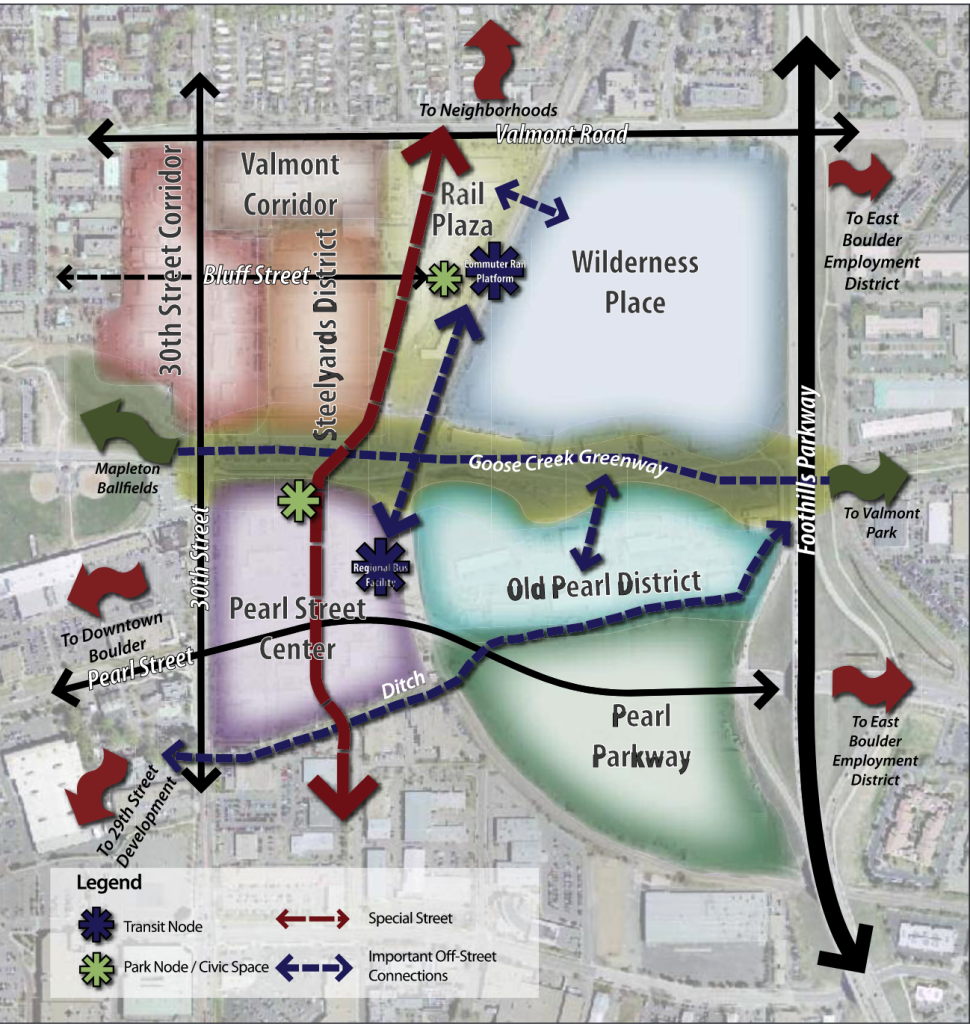

Finally, at the northern terminus of the Flatiron Flyer route, lies the Boulder Junction transit village. The redevelopment area here is situated in a formerly-industrial area bordering a freight corridor that could, one day, carry commuter trains to Denver and beyond. In the meantime, a transit-oriented development built near express bus service to Denver has slowly unfolded, situated around Depot Square Station, which opened in 2016. The station, with six subterranean bus bays, a Hyatt hotel, and 71 affordable housing units, sits at the center of a planned transit village. The City of Boulder began its Transit Village Area Plan in 2007, setting the blueprint for what is another emerging dense, walkable district centered around bus transit.

The plan details how an area with low-rise strip malls, surface parking, and industrial uses would be transformed into a walkable, mixed-use development centered around transit. The vast majority of the Boulder Junction was rezoned into mixed-use, or high-density residential areas abutting the Flatiron Flyer bus depot, and future commuter rail station. The Transit Village plan set out an ambitious goal: 55 to 75 percent of all trips, including commutes, to be made by alternative modes. To support this aim, those who live or work in Boulder Junction are eligible for RTD EcoPasses, which provide unlimited bus and rail trips on the system. These passes are funded by the Transportation Demand Management District (TDM), which receives development fees and a portion of property taxes.

Today, Boulder Junction is a growing transit village, vastly different from a decade ago. Next to the Depot Square plaza and Flatiron Flyer terminal is the S’Park neighborhood, with five multifamily developments, and another currently under construction. Across Peal Parkway is Google’s Boulder Campus, and, a short bus ride away on RTD’s Hop service, are employment centers in Central Boulder, and the University of Colorado campus.

The Boulder Junction transit village is an exercise in mixed-use, multifamily development in a city with four times as many new jobs as homes. Transit connectivity and a housing crunch continue to fuel developer interest, such as a planned 89-unit second phase of the Steel Yards complex. While the vast majority of new units are market rate, the S’Park development includes 77 permanently affordable units out of its 244 total. This can be attributed to the City of Boulder’s Inclusionary Housing Ordinance that requires 25 percent of housing units in new developments to be designated as affordable, as well as density bonuses awarded with the condition of additional affordable housing units. At the same time, the City of Boulder recognizes that it can have even more influence over affordable housing on parcels that it owns. For example, in January, 2020, the City commenced construction on 30Pearl, a 120-unit complex with affordable housing, supportive housing, and units designated for an Independent Living Community for individuals with disabilities.

While Boulder Junction has been the site of considerable development, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected transit connections to the transit village. As of publication, RTD had yet to resume service on the FF4 and FF6 routes, which respectively link Boulder Junction with Denver’s Civic Station and Union Station. The disruption caused by the global pandemic demonstrates one challenge to BTOD—the perceived transience of service could cause some developers to balk. Charlie Stanfield, a long-range planner at RTD, said that capital investments, such as signage, and physical station infrastructure, were one strategy to visually differentiate a BRT line, demonstrating its value to developers.

The Denver metropolitan region, and Colorado as a whole, is experiencing widespread growth and a burgeoning housing shortage. A June 2021 analysis by the Common Sense Institute found that Colorado had a 175,000-unit housing deficit, which, to be closed, would need 54,000 new housing units to be constructed each year through 2026. Additionally, renters have faced ever rising housing cost as rents in the Denver region rose by 75 percent from 2009 to 2020. Transit village-style growth, based on existing and future BRT, could contribute to surmounting this gap. These three recent developments, which are each seeing sustained developer interest, provide models for further dense, transit-based, smart growth.

Conclusion

For planners looking to create new BRT corridors and incorporate TOD planning into the process, Cleveland is a model for legacy cities, and Denver for less dense municipalities experiencing rapid growth. In Denver and Cleveland, BRT service was created to address existing demand, becoming successful because it connected employment centers with more efficient service. For municipalities with existing BRT systems wishing to spur development, East Liberty offers an excellent case study. In Pittsburgh’s East Liberty neighborhood, demand was first created—kindled through anchor retail, then more widespread redevelopment, and finally more traditional TOD next to the station area.

Pitfalls exist, though, with the potential for service quality to change, diminish, or disappear over time – a fate that can befall any form of transportation but which may have a greater impact on BRT. Cleveland’s HealthLine, for example, ran far slower after fare collection was reinstated due to a court order. As previously noted, the coronavirus pandemic, too, has led to the suspension of routes serving Boulder Junction Station. BRT presents its own operational obstacles that must be overcome.

BTOD follows a pattern similar to rail-oriented TOD, brought about through coordinated land use and transit planning. The lower capital and operating costs make BRT an attractive investment for cities. Still many factors affect its success: the strength of the market, the quality of the transit service, existing land use regulations, proximity to anchor institutions, etc. Rapid bus routes, like any transit route must, as Spieler writes, “serve places where many people want to go.”

For BTOD to flourish, municipalities, planners, and transit agencies must commit to collaborate, assess the unique needs and strengths of their area, and use their unique resources and jurisdictions to achieve reliable Bus Rapid Transit serving a variety of destinations, and land uses that complement that service.

Case Studies Summarized

| Location | Service | Peak Frequency | Anchors | Successes | Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleveland OH | HealthLine | 15 minutes | Cleveland Clinic, Cleveland State University | High ridership, billions in adjacent development | Uneven infill development |

| Pittsburgh PA | MLK Jr. East Busway (P1, P2) | 8 minutes | Google, Whole Foods, Home Depot | Neighborhood revitalization | Initial lack of developer interest, then housing affordability and displacement |

| Denver Metropolitan Area CO | Flatiron Flyer (FF1, FF2, FF3, FF4, FF5, FF6) | 15 minutes | Google, Hyatt Hotel, employment centers along route | Several BRT-based transit villages | Housing affordability, impermanent service |

Resources

Adams, Liam. 2021. Study rates Westminster near top in apartment growth. The Brighton Blade. https://www.thebrightonblade.com/stories/study-rates-westminster-near-top-in-apartment-growth,372422

Andrews, Eve. 2019. Why is bus ridership falling almost everywhere except Pittsburgh? https://grist.org/article/why-is-bus-ridership-falling-almost-everywhere-except-pittsburgh/

Belko, Mark. 2021. Some Former Penn Plaza Residents May Return to East Liberty under New Housing Plan. Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. https://www.post-gazette.com/business/development/2021/02/17/Penn-Plaza-East-Liberty-Trek-Development-Group-Mellon-s-Orchard-South/stories/202102170131

Cleveland Health-Tech Corridor. 2021. New Developments in the Health-Tech Corridor. https://www.healthtechcorridor.com/development/

Davidson, Tom. 2021. $13 Million Mixed-Income Housing Project Planned in East Liberty. Trib Total Media. https://triblive.com/local/13-million-mixed-income-housing-project-planned-in-east-liberty/

Fisher, Amber. 2020. Construction of 30Pearl Affordable Housing Begins in Boulder. Patch. https://patch.com/colorado/boulder/construction-30pearl-affordable-housing-begins-boulder

Governor’s Office of Planning and Research [California]. 2020. Bus Stations as TOD Anchors Report. https://www.opr.ca.gov/docs/20210203-Bus_Stations_Final_Report.pdf

Hendrix, Michael. 2021. Boulder’s Challenge. City Journal. https://www.city-journal.org/boulder-colorado-affordable-living?wallit_nosession=1

ITDP. 2013. More Development for Your Transit Dollar. https://www.itdp.org/2013/11/13/more-development-for-your-transit-dollar-an-analysis-of-21-north-american-transit-corridors/

Pittsburgh City Planning. 2012. East Liberty Station: Realizing the Potential. https://apps.pittsburghpa.gov/dcp/elTRID.pdf

Progressive Railroading. 2021. Colorado Gov. Polis signs Front Range passenger-rail law. Progressive Railroading. https://www.progressiverailroading.com/passenger_rail/news/Colorado-Gov-Polis-signs-Front-Range-passenger-rail-law–63918

Sasaki. 2021. Euclid Avenue Healthline Bus Rapid Transit. https://www.sasaki.com/projects/euclid-avenue-healthline-bus-rapid-transit/

Spieler, Christof. 2018. Trains, Buses, People: An Opinionated Atlas of US Transit. Island Press. https://islandpress.org/books/trains-buses-people

Wood, Tommy. 2021. Fifteen years in, Arista surges toward buildout. BizWest. https://bizwest.com/2021/03/29/15-years-in-arista-surges-toward-buildout/#

Yuen, Christopher. 2018. Basics: The Ridership – Coverage Tradeoff. Human Transit. https://humantransit.org/2018/02/basics-the-ridership-coverage-tradeoff.html