A court-style cottage cluster in Oregon. Courtesy of Sightline Institute

For some, the concept of transit-oriented development may conjure hulking structures clustered around stations. But transit-oriented development is not monolithic. Indeed, it is based upon a principle of land use, not a minimum density mandate. Still the idea of density may cause reaction, the fear of dramatic change ruining a beloved neighborhood. Moreover, in certain areas, hundred-unit developments are not feasible, or advisable. Instead, transit-oriented development can manifest via subtler policies that acknowledge the historic scale of a place and build density incrementally, by leveraging historic housing typologies and innovative design. Through context-sensitive TOD, it is possible to add “gentle density” to an underdeveloped transit area, building ridership and a more cohesive urban fabric in concert with the community.

Density does not necessitate skyscrapers. The urbanist writer Andrew Price, in an article for Strong Towns, writes that relatively low-rise Union City, New Jersey, has a far greater population density (51,810 people per square mile), than tower-laden downtown Miami (27,302) or nearby Jersey City (17,396). While large-scale projects are appropriate in certain situations, in others, increased densities in transit-adjacent areas can be created using different planning tactics: by building missing middle housing, looking to the past, and innovating through architecture and design to create context-sensitive transit-friendly neighborhoods.

Planning for the Missing Middle

The 2007 book Visualizing Density, published by the Lincoln Institute for Land Policy, outlines several reasons of “Why We Hate Density.” Authors Julie Campoli and Alex S. MacLean detail the twin fears of crowding and monotony, of what they term a poor “balance between housing and population,” and a lack of variety in building patterns. These problems—due to failures of regulation and imagination—can be solved using gentle density techniques and by allowing smaller operators to build on a more granular scale, such as through the missing middle framework.

In their book Missing Middle Housing: Thinking Big and Building Small to Respond to Today’s Housing Crisis, planners Daniel Parolek and Arthur C. Nelson explain the need for increased housing stock at a variety of price points that can be achieved through a return to variety in building typologies. “These types have historically delivered attainable housing choices to middle-income families without subsidies and continue to play a role in providing homes to the ‘middle income’ market segment that typically straddles 60 percent to 110 percent average median household income, in new construction, for-sale housing” (Parolek & Nelson, 2020).

Parolek and Nelson explore these housing models in detail, offering special zoning specifications for each. Starting at the lowest intensity are duplexes (either stacked or side-by-side), triplexes, fourplexes, courtyard buildings, cottage courts (approximately six small homes), townhouses, multiplexes, and the live-work “flexhouse.” All of these building styles exist in communities across the country, but post-1940, their construction has been vastly diminished in favor of single-family detached sprawl.

According to the authors, viable public transportation frequently requires a minimum of 16 dwelling units (du) per acre. Missing middle housing, much of which can resemble traditional single-family dwellings in both appearance and building envelope, provides a viable solution to inject higher density into an area without dramatically altering its character. Parolek and Nelson point out that the results of many well-intentioned transit-oriented development zones have been awkward, provoking resistance from communities. They write: “Missing Middle Housing should be considered in some transit-rich locations as an alternative or as a transition from the larger buildings directly adjacent to stations into neighborhoods. Not all transit-oriented development needs to be five-plus stories.”

Looking to the Past

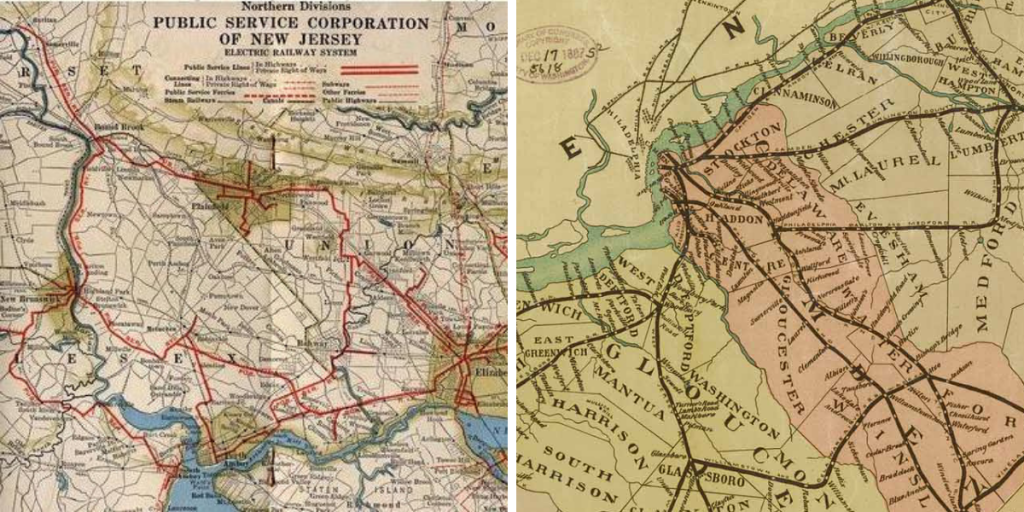

Many streetcar suburbs demonstrate the efficacy of missing middle building patterns. Places like Paterson, Newark, Highland Park, and Pitman in New Jersey retain dense, mixed-use development from this era, and provide enduring examples of smaller-scale TOD that easily integrates with a traditionally single-family neighborhood. Highland Park and Pitman, for example, have built examples of almost all typologies outlined in Parolek and Nelson’s book.

Perhaps what is most remarkable about these housing types is their normalcy; they blend in easily with a typical low-rise pattern. These housing styles were built, initially, because of their historic transit connections. Beginning in 1897, electric railways ran from Highland Park to New Brunswick, Metuchen, Elizabeth and Perth Amboy. In Pitman, transit connections were created via the 1861 completion of the West Jersey & Seashore Rail Road, which provided service through the Borough to Camden and, at its southern end, to Cape May (Wilson, 1899). Because of their transit connectivity, these municipalities were able to develop relatively high housing densities for their size. Pitman’s railway, currently used only for freight, may be reused for passenger service via the planned Glassboro-Camden Light Rail, which will reconnect the municipality to the Philadelphia-Camden area.

Past examples of transit-oriented development provide time-tested starting points for future planning. They prove, too, that it is possible—sometimes advisable—to densify using the granular, missing middle approach, densifying slowly, in ways that more evenly distribute development.

Innovating Through Design

While present TOD practice may be focused on large and medium scale development, some cities and planning agencies are exploring alternative methods of providing much-needed densification. The City of Los Angeles, currently experiencing an acute housing crisis and undergoing a massive transit network expansion, recently solicited ideas from the general public for new ways to add units in traditionally low-density, sprawling neighborhoods.

The winners of the Low-Rise: Housing Ideas for Los Angeles design challenge provided innovative solutions for infill density. The California Branch-style Home, the first-place entry for the Corners category involved several structures arranged at the edges of a lot, with a courtyard-style common area at the center. Hidden Gardens, the selection for the Fourplex category, featured several two-story buildings arranged across a lot, with a “Community Easement” creating communal space in between. The Subdivision category’s first place entry, Green Alley Housing, imagined duplexes abutting pedestrianized alleyways. Though none of the winners of the Low-Rise competition are currently planned for construction, they do demonstrate that denser, multi-unit housing need not be intimidating, and provide salient examples to soothe community members concerned about the effects of density.

In some urban, transit-rich areas, irregular parcels prove obstacles to traditional transit-oriented development. The Philadelphia-based architecture and planning firm, ISA, specializes in creating small- to medium-scale infill plans, such as designing for small, narrow parcels that can be geometrically difficult to develop. One model plan, the Loose Fit, proposes a long mezzanine-unit of variable height that could be constructed in a lot too narrow for traditional development. Another built example is the XS House, which sits on an 11 foot-wide by 93 feet-long parcel, with seven apartments included in the five-story structure. The firm has also explored creating a model for lower-cost infill development, the 100K Houses prototype, a hyper-efficient model at a cost of $100 per square foot, versus a typical square footage cost of $155 in the Northeast region. Thus far, eight of these low-cost homes have been constructed in a transit-adjacent area in Philadelphia.

In New Jersey, the startup housing company Vessel Technologies partnered with the City of Trenton on a new affordable housing development. Vessel’s designs are tailored to smaller lot sizes, beginning at 15 units on 50 by 100 foot lots—below traditional multifamily densities, but easily increased to the 16 du per acre required to support transit. Josh Levy, executive vice president of Vessel, recently spoke at the 2021 New Jersey Planning and Redevelopment Conference on the company’s vision to provide affordable, quality housing. “This is the kind of housing that existed in the not-so-distant past,” Levy said. Vessel’s work in Trenton is the construction of a six-unit modular building in the Canal Banks Redevelopment Zone. The project commenced in June 2021, with an estimated completion date in early September.

Cities, recognizing the need to diversify their housing stock, are doing their part, too. In 2019, Minneapolis eliminated their single-family zoning code, and, in July 2021, Raleigh legalized duplexes and triplexes. The City of Chicago commenced several pilot studies allowing Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), another strategy that supports low-cost densification.

Smaller-scale development, such as ADUs or missing middle housing, lowers the barrier of entry for developers. Local builders, who may not have the means to build hundred-unit complexes, can much more easily construct duplexes or triplexes. Even skilled homeowners can try their hands at building ADUs on their property. With another unit comes the opportunity for passive income, which can be beneficial for first-time homeowners, older persons wishing to remain in their homes, and others looking to reduce their housing costs—all of which contribute to stronger communities. While these tactics may not generate headlines, they can effectively increase density in transit-rich areas without costly rezoning processes and widespread community opposition, while simultaneously enriching a local economy in a far more equitable manner than the status quo.

Returning to Transit

All across the nation, the built environment reflects past transit-oriented eras, when railways and trolley tracks were the predominant method for mobility. Though some railways have disappeared, their legacy remains imprinted in land use patterns, from mixed-use, walkable cores to streetcar suburbs filled with multi-unit structures. As we return to transit, and look to redevelop around it, these buildings that have endured provide valuable lessons for successful TOD. The Missing Middle approach, which preserves neighborhood form while expanding density and housing affordability, builds off the time-tested lessons of legacy transit-oriented development. Innovations in design and technology upgrade these concepts with new methods and materials, ideally creating cost reductions that can be passed on to the consumer.

One path moving forward is to study the transit-oriented development patterns of the past, review the current practices for missing middle, modular, and infill housing, and utilize the tools of planning to imagine context-sensitive TOD in a low-density transit area. Transit agencies can be a supportive partner to this end as they collaborate with municipalities and contribute planning resources for a mutually-beneficial arrangement that can result in more transit usage, more residents across a range of incomes, and diversified, resilient economic development for the municipality.

Resources

APA New Jersey & New Jersey Future. (2021, June). Beyond the Bull$hit: Practical, Applicable Solutions that Get Housing Done. New Jersey Planning & Redevelopment Conference 2021.

Baca, A., McAnaney, P., Schuetz, J. (2019, December 4). “Gentle” Density Can Save Our Neighborhoods. The Brookings Institution. https://www.brookings.edu/research/gentle-density-can-save-our-neighborhoods/

Fisher, Alan. (2020, October 3) A Car-Free Neighborhood in an Old New Jersey Town. YouTube.com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dVeSiWTU74s

Freishtat, Sarah. (2021, June 14). The City Has Received Applications to Add More than 160 Coach Houses and Granny Flats. Will they Help Solve Chicago’s Affordable Housing Shortage? Chicago Tribune. https://www.chicagotribune.com/real-estate/ct-re-chicago-coach-house-granny-flat-20210614-izkrbdzuqvaw7nplpfk3e7qcee-story.html

HomeGuide. (2021). How Much Does It Cost to Build A House? HomeGuide. https://homeguide.com/costs/cost-to-build-a-house

Insider NJ. (2021, June 9). Trenton Celebrates Groundbreaking on Vessel Housing Redevelopment Project on Perry Street. Insider NJ. https://www.insidernj.com/press-release/trenton-celebrates-groundbreaking-vessel-housing-redevelopment-project-perry-street/

IS Architects. Leftovers. IS Architects. http://www.is-architects.com/leftovers

Johnson, Anna. (2021, July 7). Raleigh Approves “Gentle Density” Measure to Add Duplexes, Townhomes to Neighborhoods. The News & Observer. https://www.newsobserver.com/news/local/counties/wake-county/article252617598.html

Parolek, Daniel & Nelson, Arthur C. (2020). Missing Middle Housing: Thinking Big and Building Small to Respond to Today’s Housing Crisis. Island Press.

Price, Andrew. (2018, January 3). Surprising Approaches to Achieving Density. Strong Towns. https://www.strongtowns.org/journal/2018/1/3/comparing-approaches-to-achieving-density

University of Texas Libraries. (1913). Map of Electric Railway Lines. The University of Texas at Austin.

United States Census Bureau. (2010). DP-1 – Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for Highland Park borough, Middlesex County, New Jersey. United States Census Bureau.

United States Census Bureau. (2010). DP-1 – Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics: 2010 for Pitman borough, Gloucester County, New Jersey. United States Census Bureau.