Guidebook to Funding Transportation Through Land Value Return and Recycling. (2018). NCHRP Research Report 873. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press.

The Guidebook to Funding Transportation Through Land Value Return and Recycling, published by TRB’s National Cooperative Highway Research Program (NCHRP) in 2018, provides a practical guide to the infrequently utilized practice of recapturing land value increase to fund transportation infrastructure.

The infrastructure needs of transit systems in the U.S. typically far outweigh available funding sources. As stakeholders look for alternative revenue sources, land value return and recycling offers a number of benefits to public agencies that build, maintain, and operate transportation systems as well as to the public who depend on these systems.

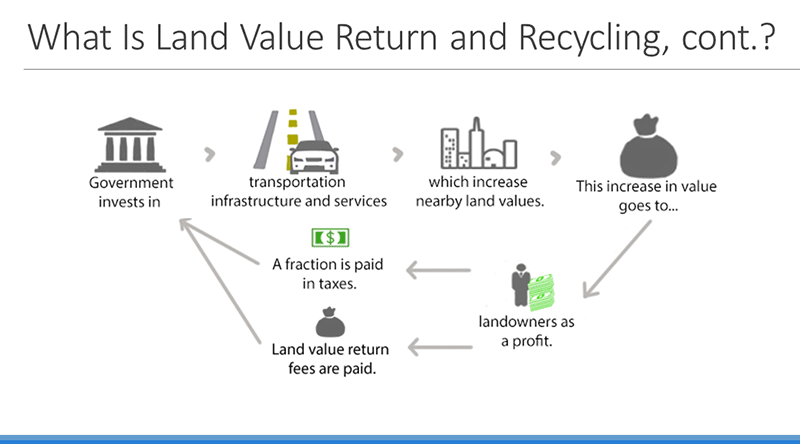

The authors define land value return and recycling as “the public recovery of a portion of the increased land value that is created by public investment that results in performance gains in the transportation system or other infrastructure.” When well-performing transportation investments increase land values, a few well-served landowners reap the benefit. Land value return seeks to return a greater proportion of this profit to the public sector via fees or taxes, which can then be reinvested in the maintenance of transportation infrastructure. There are a variety of methods for deploying land value return and recycling, several of which are variants of traditional property taxation. In a 2018 article explaining the mechanism, Rick Rybeck, Director of Just Economics, describes that all communities in the U.S. practice a form of land value return and recycling through property taxation. Within the traditional property tax system, which is based on both improvement value and land value, landowners can hold off on development to drive demand, increase prices, and induce land speculation and sprawl. The goal of land value return is to influence development near new transportation infrastructure, reducing undesired outcomes such as speculation and sprawl.

Land value return and recycling has been sparingly used to-date in the U.S., so any agency that plans to implement the method will need to build stakeholder support and communicate the benefits to the public. Land value return methods are based on the “beneficiary pays” principle, which suggests that “those who benefit from the transportation system should bear responsibility for its costs.” This principle informs user fees such as parking, tolls, and transit trip costs. Individuals who directly use and benefit from the system pay a fee that goes towards the maintenance of that system. In the case of transportation infrastructure, in addition to increased land value, landowners gain direct benefits—use of the transit system—and all gain indirect benefits such as reduced roadway congestion. Like a user fee, a tax or fee on landowners who benefit from transportation infrastructure can help create a funding system that is perceived by the public as fair and equitable.

The study authors identify several case studies that describe a variety of different methods that can be used to return land value. In Washington D.C., WMATA has successfully used a joint development method since the 1970s that allows for the public land or air rights to be sold or leased for development. In joint development, projects are undertaken cooperatively between a public agency and private developer, with each bearing some of the risk and gaining some of the reward. In the WMATA case, a joint development fee was charged for the rights to develop the land adjacent to a transit facility, or an interface fee was used to create a direct connection between private property and a transit facility, such as an entrance from a private building to a transit station. Joint development has contributed to WMATA’s goal of promoting transit-oriented development to reduce automobile dependency, encourage mixed-use development with housing, attract new riders, and generate revenue to maintain the agency’s long-term financial stability.

Another method that been used abroad is land leasing. In Hong Kong, all of the land is owned by the government which has sold development rights for land above, and adjacent to, future stations to the rail operator MTR at a lower “prerail” price that does not include the value added of future transit access. MTR subsequently resells the rights to developers at an increased “with rail” price, calculating the location’s higher value once there is transit access. The difference in price funds the construction of the station as well as development profits. This model, along with other land-related revenues, has funded 79 percent of infrastructure investments, generating profits and high ridership numbers. While Hong Kong’s situation is unique, the process shares similarities with the 19th century development of transcontinental railroads in the U.S. Railroad companies were given land rights along the routes to develop stations and towns, which provided economic returns through increased land value from the railroad presence.

The report’s authors stress that land use and transportation are inextricably linked. Transportation investments can influence land use and development, and land use and development can directly determine the demand and use of a transit system. Since property taxes are assessed at the local level, implementing land value return requires partnerships between multiple agencies and levels of government and involves buy-in from private investors. Despite the attractive benefit, any group looking to implement land value return will likely face many hurdles. They will need to gain stakeholder support, ascertain legal prerequisites, establish new administrative practices, and identify the appropriate geographic scale for implementation. Yet, as transportation investments face constrained budgets, land value return and recycling offers an overlooked revenue source and contributes to the goals of many stakeholders to reduce sprawl and promote smart growth.

For more information on land value return, also see:

Rybeck, R. 2018. Financing Infrastructure with Value Capture: The Good, The Bad & The Ugly. Strong Towns. February 21.

Suzuki, H., Murakami, J., Hong, Y.H. and Tamayose, B., 2015. Financing Transit-Oriented Development with Land Values: Adapting Land Value Capture in Developing Countries. The World Bank. Our review of this report can be found here.