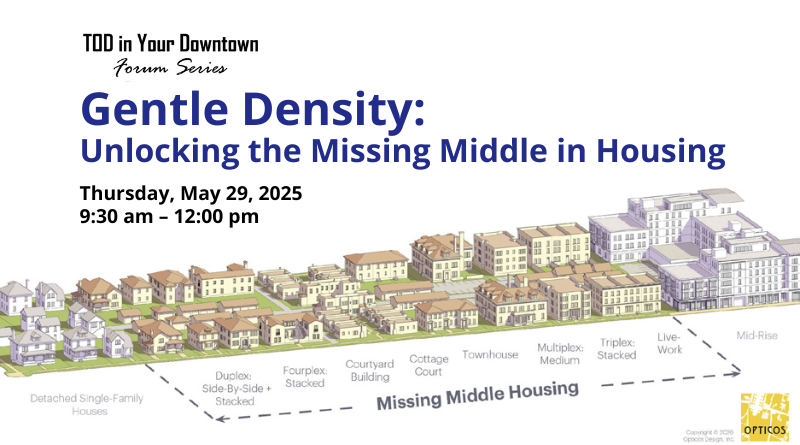

On May 29, NJTOD, NJ TRANSIT’s Transit Friendly Planning (TFP) program, and Downtown New Jersey hosted “Gentle Density: Unlocking the Missing Middle in Housing” at NJ TRANSIT’s new headquarters in Newark, as part of the TOD in Your Downtown Forum Series. The event convened experts and practitioners from municipal governments, non-profit organizations, and the private sector to discuss best practices for implementing gentle density and missing middle housing in New Jersey.

Welcoming Remarks

Stephanie DiPetrillo, Principal Investigator of NJTOD, and Michael Swan, Assistant Director of NJ TRANSIT’s TFP program, started the event with welcoming remarks. Ms. DiPetrillo highlighted NJTOD’s role in supporting transit-oriented development through education and research, a mission made possible through its partnership with NJ TRANSIT. She also spoke of the importance of middle housing in expanding homeownership opportunities, noting how her own family benefited from greater housing choice in both New Jersey and New York.

Mr. Swan discussed the TFP program’s role at the intersection of land use and transit planning, highlighting two key resources: Transit Friendly Planning Guide and Gentle Density and Missing Middle Housing in New Jersey. Both guides offer practical information and best practices to help municipalities implement transit-oriented development and gentle density strategies.

Panelist Presentations

Following the welcoming remarks, Courtenay Mercer, Treasurer of Downtown NJ, CEO of Mercer Planning Associates, and the event’s moderator, introduced Downtown NJ’s mission to strengthen New Jersey’s downtowns through outreach, education, and advocacy. She expressed enthusiasm towards the panel’s focus, describing middle housing as the housing that once formed the backbone of our walkable, mixed-use communities. She then invited the panelists to share introductory presentations on their work advancing middle housing and gentle density in New Jersey.

Adam Tecza, an urban design practice manager at FHI Studio, now IMEG, opened by outlining the urgent need for middle housing and gentle density in the state. Drawing from the Gentle Density and Missing Middle Housing in New Jersey guide he co-authored with TFP, he clarified a key distinction: middle housing refers to the product or physical types of housing—such as duplexes, townhomes, and garden apartments—while gentle density refers to the policy framework that enables these housing forms through zoning changes, variances, or incentives.

Tecza emphasized that middle housing plays a vital role in expanding housing options, particularly owner-occupied homes, amid a statewide housing shortage. With rising costs for single-family homes and new development primarily focused on large multi-family developments, middle housing offers a critical alternative that better aligns with shifting demographics—including smaller household sizes and fewer families with children.

He highlighted several housing types featured in the guide, including cottage courts and multiplexes, along with planning and zoning strategies to support them. Key approaches include demographic and spatial analysis to determine feasibility, community engagement to build support, and flexible zoning tools such as dynamic lot standards and context-sensitive design guidelines. Tecza shared a case study of a community that prioritized front porches as a defining neighborhood feature; the municipality allowed increased density if the new housing preserved that design element—demonstrating how thoughtful policy can maintain neighborhood character while accommodating growth.

Chris Cosenza, Project Manager at LRK and municipal planner for Metuchen and Highland Park, highlighted the role of design in achieving density that doesn’t feel dense—what he called gentle density. He began with an aerial image of a Princeton neighborhood that, at first glance, appears to be a typical single-family community. In reality, it includes garage ADUs, duplexes, quadplexes, and townhomes. Princeton achieved this through context-sensitive urban design, allowing for a variety of housing types while preserving neighborhood character.

Cosenza described several projects that demonstrate these principles, including Metuchen’s Franklin Square and Central Square redevelopment projects, located at the edge of the borough’s downtown. He highlighted best practices such as modest setbacks, mature landscaping, patios or walk-up entries that reflect surrounding homes, and rear-lot parking. These features help integrate higher-density housing into existing communities without disrupting their look and feel.

Allison Ladd, Deputy Mayor and Director of Economic and Housing Development (EHD) for the City of Newark, discussed her experience implementing affordable gentle density in an urban context. She noted that although she was initially unfamiliar with the term “gentle density,’ she quickly recognized that Newark had already embraced many of its principles.

Ladd described several initiatives that have expanded middle housing options in the city. During Newark’s early-2020s Master Planning process, the City considered legalizing ADUs in all residential zones. Although community pushback limited the outcome, a 2023 zoning change ultimately allowed for ADUs in R-1 zones. Newark also expanded its rent control ordinance—previously limited to large multi-family housing—to include middle housing, capping annual rent increases at four percent.

Additional strategies include allowing duplexes and triplexes to be built without variances, leveraging city-owned land to facilitate new housing, and launching Equitable Investments in Newark Communities program. Through this initiative, the City partners with local developers or nonprofits to rehabilitate single-family or middle housing homes into affordable homeownership opportunities.

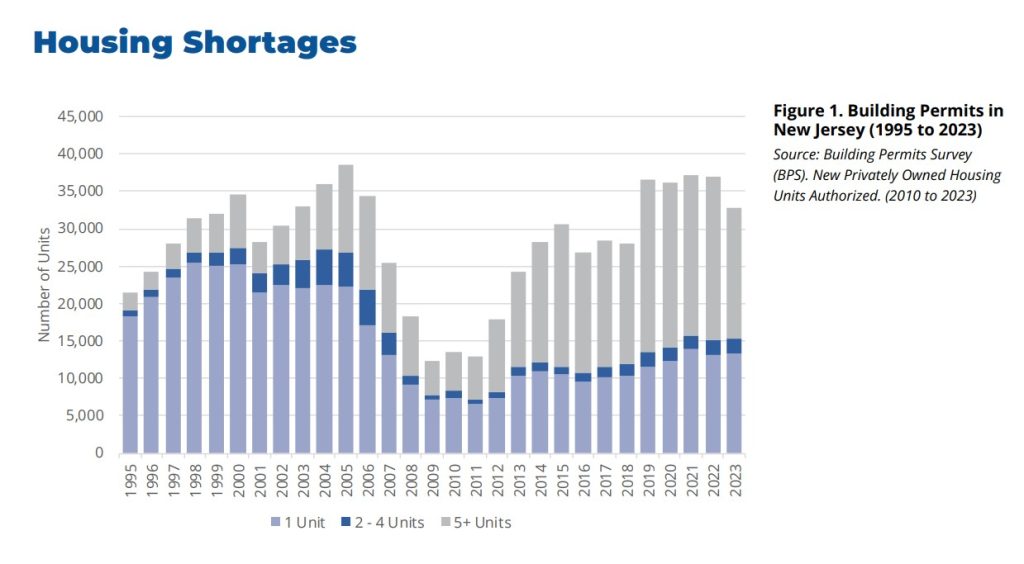

Chris Sturm, Policy Director for Land Use at New Jersey Future, concluded the panelist presentations by underscoring the urgent need for new housing construction–especially middle housing–and exploring how the local initiatives could be scaled to the state level. Since 1950, the share of 2–4 unit structures in New Jersey has declined relative to both single-family detached homes and large multifamily buildings. This shift, combined with an overall slowdown in housing production—has contributed to a worsening affordability crisis. Today, New Jersey ranks first in the nation for the percentage of 18-to-34-year-olds living at home, fourth in net domestic outmigration, and seventh in median rent.

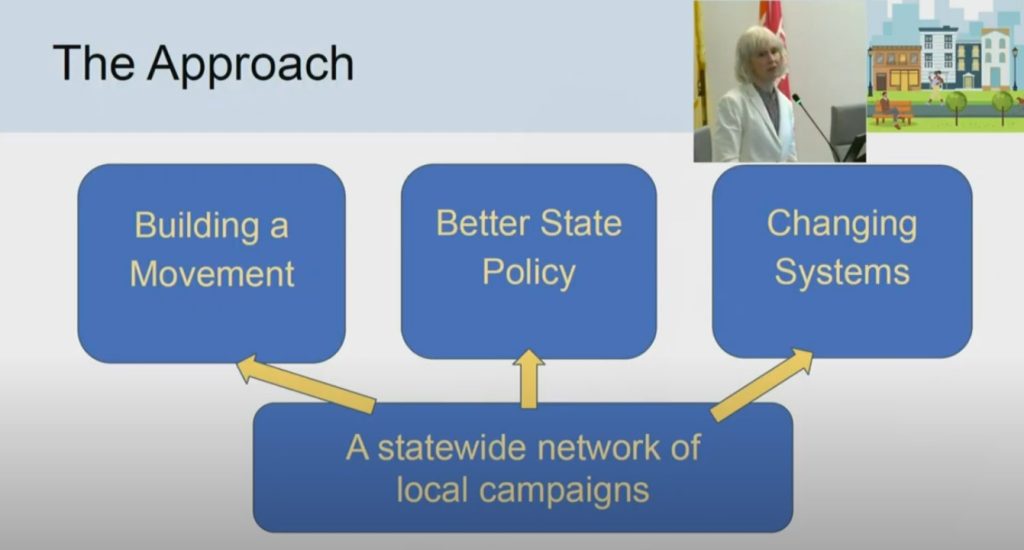

Sturm stressed that reversing these trends will require a coordinated network of local campaigns focused on reforms such as permitting ADUs, reducing parking requirements, and enabling compact transit-oriented development. She also called for broader policy changes at the state and federal levels. To effectively address affordability, she outlined four guiding principles: increase housing production, strengthen tenant protections, advance zoning reform, and improve government efficiency.

Discussion

Moderator Courtenay Mercer opened the discussion by posing a central question drawn from the presentations: How can we gain community buy-in for gentle density?

“How can we gain community buy-in for gentle density?“

Chris Cosenza responded by highlighting the importance of trust—particularly in gaining planning board support for variances and community acceptance of higher-density projects. He explained that trust is built through transparency and collaboration among developers, municipalities, and residents. When community members feel heard and see designs that reflect the existing character of their neighborhoods, they are more likely to support moderate increases in density. While large multi-family developments often face resistance, well-designed infill that blends with its surroundings can win support over time, leading to gradual increases in density.

Allison Ladd echoed the importance of trust and noted that in Newark, rebuilding it is an ongoing process. Historically, many past planning decisions excluded public input. Today, the City is working to reverse that pattern by adopting a more transparent, consistent, and practical planning process. While Newark’s effort to legalize ADUS fell short of its broader goals, Ladd emphasized that the City’s evolving approach represents meaningful progress toward rebuilding public confidence.

Adam Tecza pointed out that housing often represents a household’s largest financial asset, so it’s understandable that planning decisions can generate apprehension. Residents may worry about how changes in their neighborhood could affect their retirement or long-term savings. Tecza stressed that planners have a responsibility to take an educative approach–clearly outlining the potential costs and benefits of proposed development—so that community members can make informed decisions about the future of their neighborhoods.

Chris Sturm added that one of the most compelling national narratives around housing centers on the idea that essential workers—such as teachers, nurses, and first responders—should be able to afford to live in the communities they serve. This message, she noted, resonates widely and can help build broader public support for gentle density and middle housing reforms.

Courtenay Mercer continued the conversation by asking: What kind of pushbacks against middle housing have you experienced?

“What kind of pushbacks against middle housing have you experienced?”

Allison Ladd responded by reflecting on Newark’s effort to introduce ADUs, which faced resistance on multiple fronts. Concerns ranged from increased traffic to general discomfort with change and a lack of understanding about the role of ADUs. Some residents viewed the proposal as a tool for developers to build more housing, potentially leading to displacement. Ladd emphasized that this opposition was rooted in a broader lack of trust.

Adam Tecza suggested that ADUs may not be the most effective middle housing solution in many communities. While cities like Newark may have the physical capacity for them, the high cost—often up to $200,000 per unit—can limit their feasibility. Given this, he argued that ADUs often require a disproportionate of amount of political capital relative to the housing benefit they provide. Instead, he recommended duplexes and triplexes, which offer more scalable and cost-effective gentle density solutions. That said, Tecza acknowledged that ADUs can be quite successful when integrated into new development from the outset.

Chris Sturm offered a difference perspective, sharing that she has had a positive experience with ADUs. While they may not always be affordable, she said, they still expand housing choice. She also noted that ADUs often preserve the visual character of a neighborhood more effectively than duplexes or triplexes. Drawing from her experience in Seattle, where middle housing is fully legalized—Sturm noted that ADUs can be an important part of a broader strategy for increasing housing options.

The final question asked to the panelists focused on affordability: How can we keep middle housing affordable?

“How can we keep middle housing affordable?”

Allison Ladd explained that Newark’s ADU policy does not include an affordability requirement by default. However, if a developer seeks access to city resources, they must agree to place an affordability restriction on the unit.

Adam Tecza framed the affordability issue as an issue of housing supply. While a newly built duplex might initially be priced at over $1 million, he noted that prices will begin to stabilize as more housing is built and supply starts to meet demand. He also cautioned against applying affordability mandates to middle housing, stating that while inclusionary zoning works well on larger multi-family developments, it could inadvertently discourage the construction of smaller-scale housing types.

Chris Cosenza shared his experience with Princeton’s ADU ordinance. While it didn’t lead to more affordable housing per se, it did enhance housing choice. For example, a $1.2 million house may be converted into two $800,000 condominiums—still expensive, but more accessible to a broader range of buyers.

The panel concluded with a Q&A session. Attendees raised questions about how to balance middle housing policies with developer profitability, maintain housing quality in rent-controlled 2–4 unit buildings, measure the impact of TOD and reduced parking, and continue to build community trust in cities like Newark.

Megan Massey, Director of Transit Friendly Planning at NJ TRANSIT, closed the event by thanking the panelists, notifying attendees that a follow-up survey would be sent, and announcing NJT’s upcoming presentation on the Route 9 TOD project at the NJ Planning and Redevelopment Conference on June 13 at the Hyatt Regency in New Brunswick.

Looking Ahead

As New Jersey confronts mounting pressure to address its housing affordability crisis, conversations around middle housing and gentle density have taken on new urgency. Planners, developers, advocates, and municipal leaders came together to explore how thoughtful design, policy reform, and community engagement can expand housing options without compromising neighborhood character. The panel shared real-world insights, practical strategies, and a collective commitment to rethinking land use to meet local needs and statewide goals.