NOTE: In 2008, we reported on some of the benefits of bus rapid transit (BRT) and cities that have implemented it, including Pittsburgh and Cleveland. Since then, both cities have completed or are in the planning stages of new BRT lines. Drawing on interviews and data from new studies on the effects of BRT on land development – primarily the Institute for Transportation & Development Policy’s (ITDP) 2013 report More Development for Your Transit Dollar: An Analysis of 21 North American Transit Corridors – we return to Pittsburgh and Cleveland for an in-depth look of cutting-edge BRT in the United States.

Introduction

Sixty years ago, the Pittsburgh and Cleveland skylines were dominated by a mix of old industrial manufacturing buildings, high rises, and a smoky haze from nearby iron and steel plants. Since then, these once-booming industrial cities have overcome some of the hardships faced by many others in the rust belt, greeting the 21st century with sense of optimism inspired in part by investment in new development and transportation infrastructure in their respective downtowns. Like many American cities, Pittsburgh and Cleveland were hit hard in the post-WWII years by residents leaving the downtown for nearby suburbs. However in the past two decades, people have begun to return, attracted by economic opportunities and to cultural, commercial, and recreational amenities. And in some Pittsburgh and Cleveland neighborhoods, BRT is playing an integral role in spurring investment for residents rebuilding for the 21st century.

Cleveland: A BRT Archetype

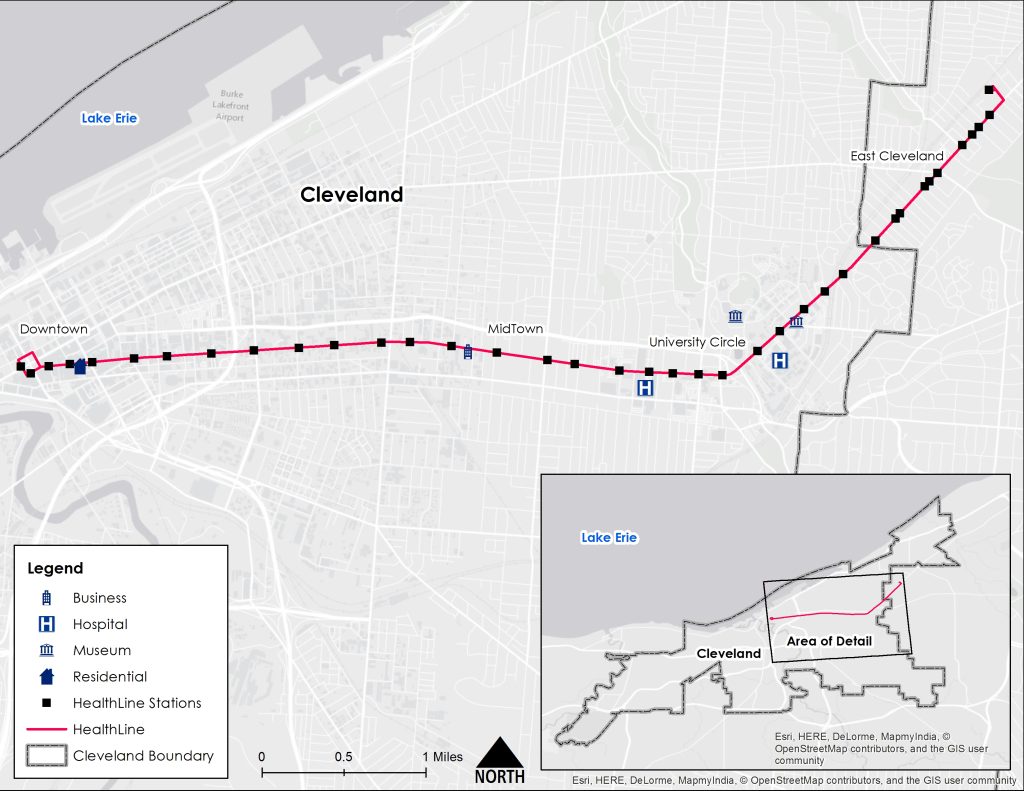

As one of only two systems in the country given a silver rating by the ITDP, Cleveland’s HealthLine is perhaps the most successful BRT in the United States. This is due in no small part to the TOD investment it spurred along its 7.1 mile route. The HealthLine connects downtown Cleveland with East Cleveland and links several neighborhoods and major institutions including two universities, two museums, and two health organizations that inspire the route’s name, the Cleveland Clinic and University Hospital. The city partnered with and received partial funding from both of these health institutions.

As was the case in Pittsburgh, when discussions began in the 1970s Cleveland’s leaders initially envisioned rail – first subway, and later light rail – serving Euclid Avenue. This idea was scrapped in favor of BRT when the cost of the locally preferred alternative, light rail, approached $1 billion. In 1999, the Northeast Ohio Areawide Coordinating Agency, the metropolitan planning organization for northeastern Ohio, presented initial project details to the public.

From the start, Cleveland had more in mind than just a transit line. The Greater Cleveland Regional Planning Authority (GCRTA), which operates the line, took a broad view of the potential impact of the project and considered what would attract people to the bus and developers to the surrounding corridor. This comprehensive approach led GCRTA to think more expansively about the improvements that needed to be made. Decisions that supported the overall success of the BRT included burying power lines, rebuilding out-of-date sewer and water lines, and adding street-level amenities such as bicycle lanes, improved sidewalks, and public art along the route. The GCRTA also designed and adopted several infrastructure and operational improvements to decrease travel time along the route. In order to minimize delays due to traffic, the agency built 4.5 miles of dedicated bus lanes. To reduce dwell time, the agency adopted two strategies. They decreased the number of bus stops on Euclid Avenue from more than 100 to just 36. They also implemented off-board fare collection. Passengers must pay at a machine prior to boarding. Altogether, the project cost just $200 million, including infrastructure and street amenities, funded by an array of federal and state sources.

Recognizing that government support was needed to support land development near the BRT, the City promoted the coordination of land use planning and BRT planning. The 2007 update to Cleveland’s comprehensive plan – Connecting Cleveland 2020 Citywide Plan – called for TOD “in proximity to transit stations and major bus stops in order to support public transit and strengthen the competitiveness of urban neighborhoods” (emphasis added), and specifically recommended TOD be directed to Euclid Avenue, among other locations. Further, the city used a number of financing incentives to attract developers to older industrial and vacant sites, including New Market Tax Credits, Federal Supplemental Empowerment Zone loans and tax credits, the City’s Vacant Property Initiative, and various brownfields clean-up and transportation grants from the state and the federal government. From these efforts, a cohesive, comprehensive development strategy emerged for Euclid Avenue, with the HealthLine BRT at its heart.

The results of these efforts can now be seen. The ITDP report shows that HealthLine yielded approximately $6 billion in development investment within four years of its opening, or $114.54 million per dollar spent on transit. Cleveland’s economic development department, among others, championed the corridor to both commercial and residential developers, emphasizing the permanence of the BRT line’s infrastructure and its high quality passenger amenities. According to the ITDP report, no BRT line and just one light rail line (Portland’s MAX Blue Line) has spurred as much investment as the HealthLine in the US. In the same time frame, ridership increased by 67 percent, to an average of 15,800 per week. Importantly, about 18 percent of riders are “choice riders”, those that have switched from traveling by car to riding the HealthLine.

Almost all of Cleveland’s downtown growth since 2008 has occurred either along or immediately surrounding Euclid Avenue, including hotels and residential conversions. One apartment complex built early on was 668 Euclid Avenue, a 236-unit complex at the west end of the HealthLine. Completed in 2010, the mixed-use building is the adaptive reuse of the former William Taylor & Sons Department Store. A HealthLine stop is located across the street.

Businesses and cultural institutions have thrived along the route as well. The 128,000 square-foot MidTown Tech Park provides space for technology and biomedical start-ups in an ideal location adjacent to the university and hospitals. In University Circle, at the east end of the line, about $1 billion in construction has been devoted to residential and commercial development, and $1 billion to university buildings and cultural institutions, including renovation of the Cleveland Museum of Art and construction of the new Museum of Contemporary Art.

Cleveland’s experience shows that successful BRT, like rail service, benefits from land use and transportation planning coordination as well as from support by both the public and private sectors. Public sector involvement can provide important funding mechanisms and land use regulation changes when needed, while buy-in from the business community and other local stakeholders help ensure that concomitant development occurs. All of this means that riders have reason to travel the line and the line serves their needs. By recognizing that BRT suited the strengths and needs of the Euclid Avenue corridor, the City has ensured that residents have affordable, convenient, and attractive public transportation for years to come.

For the first part of this series, see: