NOTE: In 2008, we reported on some of the benefits of bus rapid transit (BRT) and cities that have implemented it, including Pittsburgh and Cleveland. Since then, both cities have completed or are in the planning stages of new BRT lines. Drawing on interviews and data from new studies on the effects of BRT on land development – primarily the Institute for Transportation & Development Policy’s (ITDP) 2013 report More Development for Your Transit Dollar: An Analysis of 21 North American Transit Corridors – we return to Pittsburgh and Cleveland for an in-depth look of cutting-edge BRT in the United States.

Introduction

Sixty years ago, a mix of old manufacturing buildings, high rises, and a smoky haze from nearby iron and steel plants dominated the skylines of Pittsburgh and Cleveland. Since then, these once-booming industrial centers have overcome the hardships faced by others cities in the Rust Belt and have greeted the 21st century with a sense of optimism inspired in part by new investments in development and transportation infrastructure in their downtowns. Like many American cities, Pittsburgh and Cleveland were hit hard during the post-WWII years as residents left for nearby suburbs. However, in the past two decades residents have returned, attracted by economic opportunities and commercial, cultural, and recreational amenities. In some Pittsburgh and Cleveland neighborhoods BRT is playing an integral role spurring new investment for residents rebuilding in the 21st century.

Pittsburgh: A City of Buses

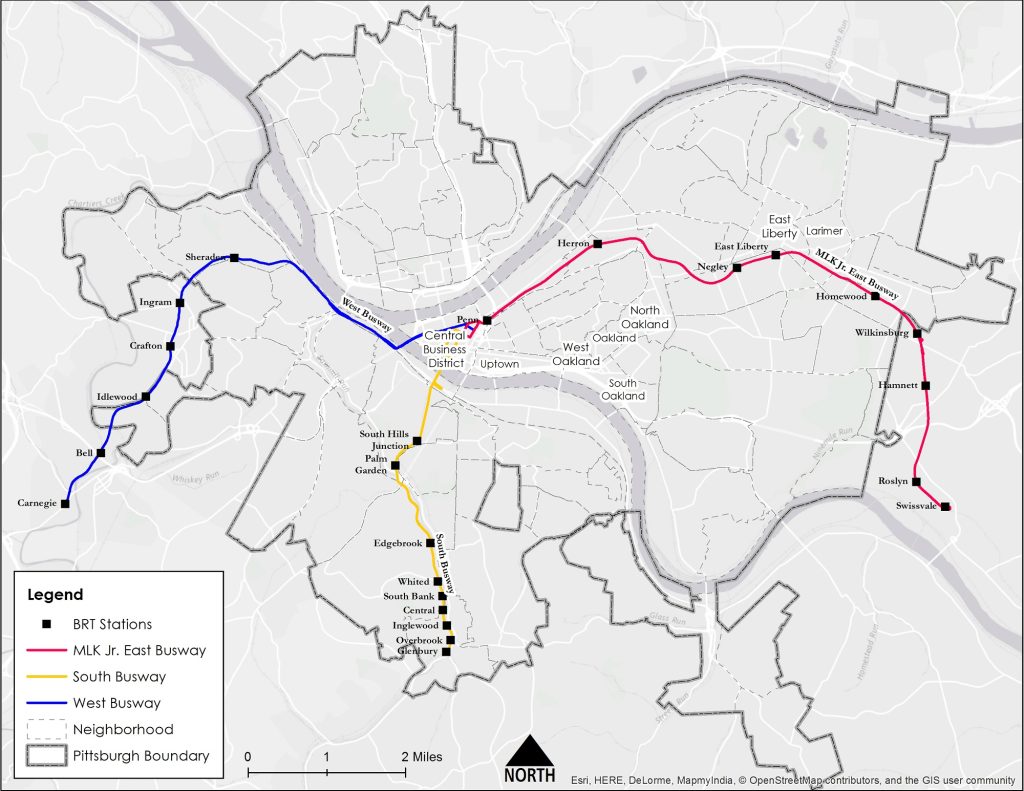

Pittsburgh, you could say, is a city of buses. While the “T” – a subway that becomes a streetcar upon crossing the famous hills that ring Pittsburgh – does connect the city’s southern suburbs to the downtown, its ridership has decreased significantly since the decades following WWII. Streetcar service in the downtown was eliminated by 1971 and replaced by buses. Buses have been a mainstay of Pittsburgh’s public transportation services since they first started serving the public over a century ago. In 1977, one of the nation’s first BRT networks, the 4.3 mile long South Busway, was constructed in Pittsburgh as a more cost effective alternative to light rail. Since then, Pittsburgh has built two more BRT routes, the Martin Luther King Jr. East Busway in 1983 (9.1 miles) and the West Busway in 2000 (5 miles), with possibly another route on the way. The South, East, and West busways all reach communities not served by the “T” and operate on former rail right-of-ways. The East Busway – which connects the East Liberty neighborhood to the downtown – cuts an hour drive down to a trip of 7 to 15 minutes by bus (see map).

The East Busway is unique by a number of standards. Of Pittsburgh’s three BRT services and light rail, it is the only one to have spurred significant development. The ITDP report documents $903 million in total investment along the line since construction, or roughly $3.59 million in development per dollar of transit investment as of 2012. Further, because it operates on its own right-of-way for a portion of the route, the line is able to offer both local and express services and can pass local buses at stations. Given these advantages, the line carries the second highest number of passengers of any BRT line in the country, at an average of 24,000 per week.

Since the East Busway began operation in 1983, the East Liberty neighborhood has lacked a unified long-term strategy to integrate the busway with redevelopment efforts. The first planning efforts aimed to address this deficit occurred in 1999. The East Liberty Development, Inc. (ELDI), with the support of the City of Pittsburgh, drafted the neighborhood’s first comprehensive plan, A Vision for East Liberty, which emphasized the area’s transit assets. That plan specifically cited the East Busway and its role in linking residents to jobs and other Pittsburghers to the neighborhood’s retail. The 2010 East Liberty Community Plan updates the earlier plan by reassessing existing conditions and advancing the redevelopment framework to move the community forward.

Since the completion of the plan, redevelopment efforts in East Liberty have focused around the East Busway. The City has found collaboration with area businesses – largely national retailers such as Target, Whole Foods, and Home Depot – a successful strategy to jumpstart redevelopment and demonstrate that the neighborhood is a good investment for future developers. City officials worked with these retailers, whose building models are usually more suitable for suburbia, to create places that work in this urban location. For example, Home Depot agreed to reduce the size of its surface parking by one-third.

In recent years, more people are calling the neighborhood their home. A number of residential rental complexes have been built, including Bakery Living, a 175-unit luxury apartment building catering to empty nesters and young professionals developed by Walnut Capital. The building is part of the larger Bakery Square development area, its centerpiece being the former Nabisco building which was rehabilitated and leased by tenants in 2009. Members of the city’s growing high-tech sector, including Google and the University of Pittsburg’s Sciences & Technology Center, have established offices in Bakery Square. See map for locations. In July 2014, US Department of Housing and Urban Development awarded a $30 million Choice Neighborhood grant to fund construction of 350 mixed income housing units in the Larimer neighborhood in eastern East Liberty. The remaining financing will come from the developer McCormack Baron Salazar and the City of Pittsburgh.

Work in East Liberty encouraged city officials and the Port Authority of Allegheny County to explore using BRT to connect the neighborhood of Oakland to downtown Pittsburgh. Just south of East Liberty, Oakland is home to two major employers, Carnegie Mellon University and the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. With such prominent institutions, the neighborhood is the state’s third largest employment center trailing only downtown Pittsburgh and Philadelphia. Despite its prominence, the neighborhood lacks a rapid transit connection to downtown and to other Pittsburgh neighborhoods. While an extension of the “T” light rail was considered for decades, in 2010, Pittsburgh and the Port Authority of Allegheny County selected BRT to meet their goals of improving travel options and spurring redevelopment in the neighborhood. Preliminary engineering and environmental studies as well as proposed designs will likely be completed over the next 18 months, with an application for federal funding set for 2016.

However, even at this early stage, Pittsburgh planning officials and Port Authority staff are coordinating land use and transportation plans. Jim Ritchie, Communications Officer at the Port Authority of Allegheny County, emphasized that “there’s decision-making on the transit side as to what the service would look like, and at the same time there is a city-based community discussion about how would this benefit the existing neighborhood, [and] where there are opportunities for new development.” Pittsburgh’s activities are a model for the nation. Their effort coordinates both land use and transportation planning so as to implement a state-of-the art BRT system that will support housing, sustainability, health, and economic development policies.

Traditionally it has been a blighted, under-invested corridor. It suffered from decline and decay. We’re looking to reinvigorate the BRT process by aligning it with a civic planning process [in Uptown].”

Grant Ervin, Pittsburgh’s Sustainability Manager

The Uptown neighborhood in Pittsburgh is another prime example of this kind of coordination. The neighborhood is situated along the Monongahela River between downtown and Oakland (see map). “Traditionally it has been a blighted, under-invested corridor,” said Grant Ervin, Pittsburgh’s Sustainability Manager. “It suffered from decline and decay. We’re looking to reinvigorate the BRT process by aligning it with a civic planning process [in Uptown]. So a key piece of the conversation is going to be engaging the community. This process will involve creating a management structure that encourages accountability with stakeholders, determining what the assessment protocols are, investigating the projects that are being planned, and installing a system of continuous measurements.”

As one of the few cities in the United States actively coordinating land use and BRT planning, Pittsburgh may be a step ahead. Many see the potential benefits for residents when affordable, convenient public transportation provides access to jobs, recreation, and housing. Pittsburgh is in the beginning stages of realizing these benefits, and more undoubtedly are to come.

For the second part of this series, see: