A lot has changed in the world of parking and mobility in recent years. While the end of private auto ownership may still be a long way off, congestion pricing (as recently enacted for lower Manhattan), increased use of ride-hailing, and other mobility options are already contributing to these changes and affecting the demand for parking in cities across the U.S. These emerging trends present opportunities as well as challenges to fostering effective transit-oriented development (TOD).

Many communities have been slow to adapt parking policies to new realities, despite research suggesting that parking continues to be oversupplied at TOD projects. A 2017 University of Utah study found that five TODs in different regions of the U.S. overestimated their parking needs. Even though these TODs built less parking than recommended by the Institute of Transportation Engineers (ITE), peak occupancy of parking spaces among the projects ranged from 58 to 84 percent.

Parking comes at a considerable financial cost. According to a survey of 12 major U.S. cities, the average cost of constructing a parking space is about $24,000 for above-ground facilities and about $34,000 for underground spaces. Developers can face land cost premiums and other financial burdens at sites near transit stations and stops when they are required to provide parking that gets little use.

Project success depends upon providing the right amount of parking in TOD areas. Too few parking spaces may discourage people who live or work far from transit stations to use transit. Too many can limit opportunities for a rich mix of uses and degrade vibrancy. Striking the right balance requires thoughtful consideration of supply and demand, pricing, regulation and integration into the built environment.

It is equally important for communities to consider ways to tap into and manage new and future mobility technologies, including ride-hailing, active transportation (e.g., bikesharing), micromobility (e.g., electric bikes and scooters), and the expected arrival of autonomous vehicles.

In New Jersey and around the country, communities are doing a serious rethink of parking. Those leading the charge have revised parking standards, implemented innovative parking management solutions, and harnessed the power of ride-hailing and other mobility options.

The Parking Revolution

A growing number of communities have realized that building new parking spaces can be inefficient and costly and that parking minimums, which require parking to be built as part of new developments, can be part of the problem.

Several communities in New Jersey are on the front lines of the parking minimum revolution. The downtown area of Jersey City, which includes a dozen planning districts near PATH and Hudson-Bergen light rail stations, have no parking minimums. The City of Newark does not require any parking when residential units are built within 1,200 feet of a rail or light rail station.

Metuchen, a designated NJ Transit Village, reduced its minimum parking requirements by 50 percent in 2014 and established maximum parking requirements, which limits total parking that developers must build. Morristown, also a designated NJ Transit Village, reduced its residential parking requirements by 25 percent within its Transit Village Core Zone, an area adjacent to the station.

Other cities nationwide have made dramatic changes to their parking requirements. In 2017, Buffalo, NY became the first city in the U.S. to completely remove all parking minimum requirements in its push for urban revival. Arlington County, VA, recently announced it will provide developers with opportunities to build fewer parking spaces for multifamily developments near its two major transit corridors—joining efforts in Washington, D.C. and three other nearby counties that share the DC metro system. According to a press release issued by the county, Arlington will grant reductions in “exchange for elements such as transit infrastructure, expanded bike parking, bike share, and/or car-share amenities on site, in addition to those already required in baseline Transportation Demand Management (TDM) requirements.”

Strongtowns.org has set up a map that tracks changes to parking minimum requirements and provides resources that allow site visitors to advocate for an end to parking minimums.

Instead of requiring parking minimums, many cities, including Boston, Chicago, Seattle, and San Francisco, have established parking maximums, which limit the amount of off-street parking a developer can build.

Learning to Share

Communities can reduce parking at a development by sharing spaces among facilities. NJIT Professor Darius Sollohub explains that shared parking works when peak parking demand occurs at different times for different facilities, thereby reducing the total number of parking spaces needed. “The Parking Authority and municipality benefit from the revenue from the garage, while at the same time incentivizing developers by allowing them to avoid having to build parking on their own,” says Sollohub.

Shared parking has been successfully implemented near transit facilities in New Jersey. Sollohub offers the example of the 568-space parking structure at the Bloomfield Station, a project built by the Bloomfield Parking Authority and the Township. The development—which comprises 200 market-rate housing units, 60,000 square feet of retail space, and a supermarket—integrates the parking facility into its overall design. Commuters, residents, and shoppers all utilize the same spaces throughout the day. Similarly Metuchen has constructed the Pearl Street Parking Garage, a shared parking facility, as part of the recent Woodmont Metro redevelopment project.

The Parking Authority and municipality benefit from the revenue from the garage, while at the same time incentivizing developers by allowing them to avoid having to build parking on their own.” ~Darius Sollohub, Associate Professor, College of Architecture and Design, New Jersey Institute of Technology

In Morristown, the 275-space Chancery Square parking facility provides building residents with 175 spaces (which are mostly used at night) and 255 monthly parking spaces for office and retail use. “Fifty to sixty percent of residents take their cars out during the day” says Robert Goldsmith, a New Jersey commercial real estate attorney and parking consultant who worked on the Morristown facility. “We’ve never had a complaint of a shortage of parking.”

PILOPs

Another effective parking solution is payment in lieu of parking (PILOP), which allows developers to pay a fee rather than build parking spaces. Cities can use PILOP revenues to construct public parking facilities, which can be used more efficiently than a private parking garage. Goldsmith points to Elizabeth and Fairlawn as municipalities that have successfully implemented PILOPs.

Fifty to sixty percent of residents take their cars out during the day. We’ve never had a complaint of a shortage of parking.” ~Robert S. Goldsmith, Redevelopment & Land Use Attorney, Greenbaum Rowe Smith & Davis

The Borough of Metuchen has used a PILOP program to fund downtown parking as the municipality pursues downtown and TOD redevelopment. Metuchen’s desire to use in lieu fees for parking was identified in its 2014 Downtown Parking Study and was eventually adopted by ordinance in March 2015. The ordinance (No. 2015-04) stipulates a $5,000 fee per required parking space for all uses and $2,500 fee per required parking space for any affordable housing unit. Developers of a recently constructed, 22-unit apartment building on Center Street paid a $100,000 fee in lieu of on-site parking. Residents have access to the nearby Pearl Street parking deck.

Implementing Demand-Based Parking Programs

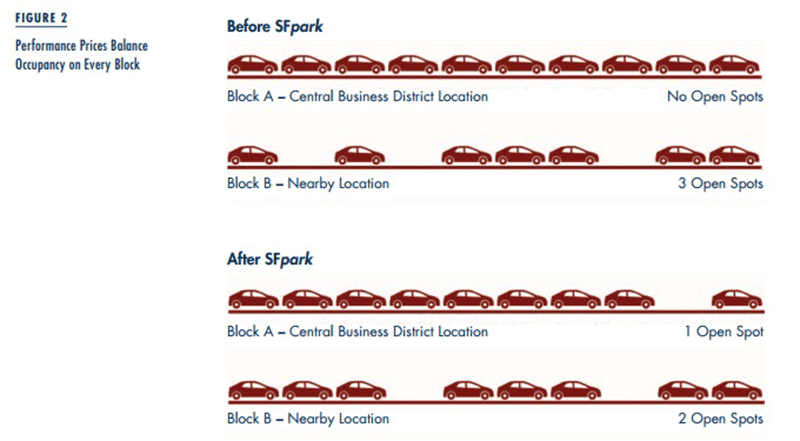

TOD communities can also avoid building more parking by making better use of what they already have. Demand-based parking programs increase parking meter prices in areas where demand is high and lower prices in less utilized areas. This strategy makes use of smart meters that track trends over time. Installation of smart meters requires a substantial upfront investment, but can help a community make more efficient use of land. This is especially important for TOD projects, where every bit of land is valuable.

In New Jersey, Asbury Park approved the purchase of 12 smart parking meters in 2017 to facilitate more efficient parking payment and turnover rates. According to Michael Manzella, Asbury Park’s Transportation Manager, the City’s goal is to use pricing to achieve an 85 percent occupancy rate at all times. Prices at the Asbury Park meters adjust according to location, season, time of day, and day of week. Data collected from the Asbury Park Parking app, which allows residents and visitors to pay for and extend parking time, complements data from the meters.

Metuchen’s Borough Council approved a proposal to purchase 218 smart meters for about $120,000 in February 2018 and installed the meters in October.

Several cities nationwide are using emerging technologies to push the boundaries of demand-based parking. San Francisco’s 2011 pilot program SFpark employed smart parking meters that employ real-time data to adjust pricing based on the level of demand at a given place and time. Demand-responsive pricing, which dynamically increases or decreases prices based on demand, allows cities to adjust parking patterns and make parking easier to find. The program reduced the average time to find a space by 43 percent and the average meter price by 10 cents per hour. San Francisco has since resumed the program. Similar efforts have been successfully employed in Seattle and Los Angeles, and Washington, D.C. recently launched a pilot program.

Parking expert Donald Shoup has played an important role in changing attitudes toward paid parking. In his latest book, Parking and the City, he argues for the removal of off-street parking requirements and for charging the right price for parking. Shoup also discusses how communities can make the shift to paid parking more palatable by linking parking revenue-supported improvements to the streets where meters are located. He provides guidance on how to implement these strategies and documents successful outcomes in communities throughout the U.S. Cities around the world that have implemented a demand-based parking program.

Harnessing the Power of Ride-Hailing

Summit, NJ recently partnered with a transportation network company (TNC) that provides rail-hailing services in an effort to improve parking in the city. Residents with a paid parking pass can take Lyft to and from Summit Station for the same price as they would pay for a daily parking pass. The City first partnered with Lyft’s competitor, Uber, when the program was launched in 2016 as the first of its kind in the U.S. After the results of a survey indicated users would use the service more frequently if they could schedule rides in advance, Summit switched to Lyft, which allows its users to schedule trips up to seven days in advance.

Summit’s approach taps into the appeal of ridesharing as a way to avoid the need to park. A 2017 survey from U.C. Davis, which looked at seven major metro areas across the U.S., found that 21 percent of all adults and 36 percent of adults age 18 to 29 have used a ride-hailing service. The top identified reason for using ridesharing was to avoid the hassles of parking (37 percent).

Ride-hailing may be an effective solution to TOD-related parking issues, but it also presents challenges. Ride-hailing services can increase street traffic, and drivers often double-park and block bike and transit lanes. Washington, D.C., San Francisco, CA, and Fort Lauderdale, FL are experimenting with replacing parking spots with pick-up and drop-off areas for ride-hailing services during times of high traffic volumes in popular commercial areas.

Curbside management, which attempts to balance the needs of all roadway users (including TNCs), is increasingly becoming an important strategy for many cities. Cities may employ techniques that inventory, optimize, allocate, regulate, and manage the limited resource of curbspace to maximize mobility and satisfy the demands of multiple users. Seattle adopted a transit-friendly method of curb allocation on main streets that prioritizes freight and passenger loading over metered parking.

Planning for the Future

As part of the Hudson Yard Development in midtown Manhattan, real estate investment firm Sherwood Equities has designed a “future-proofed” residential parking structure. The garage will have 14-foot ceilings—higher than the 10-foot standard—so it can someday be transformed into a retail space, a gym, or a common area for residents. The Hudson Yard garage is an acknowledgement that the parking and mobility landscape will continue to change.

“Given the significant growth of TOD residential development, you’re probably seeing a diminution of parking demand in New Jersey,” says Goldsmith. “At the Highlands building [near the Morristown Station], a meaningful number of residents have one car instead of two, or have no cars or rely on ZipCar.”

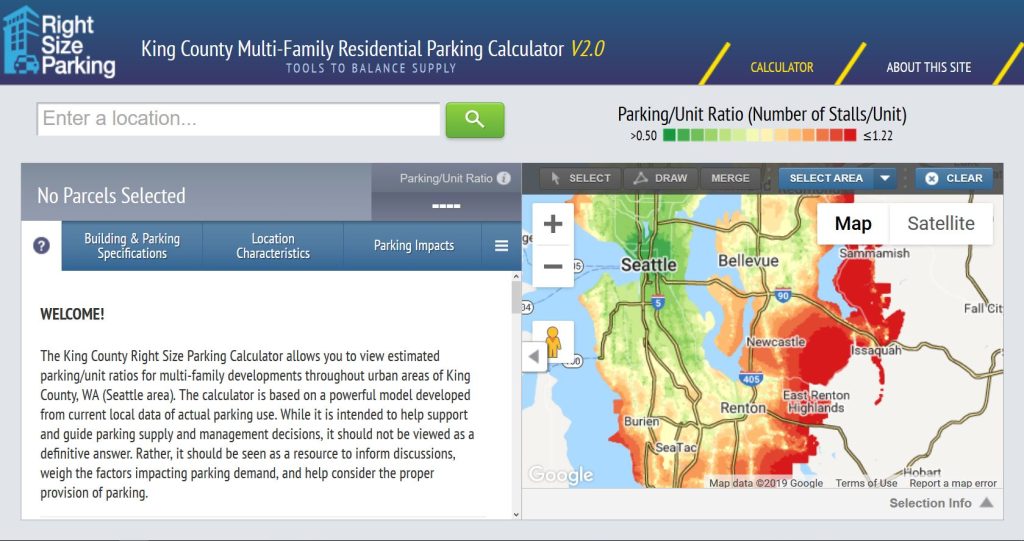

Seattle’s public transit authority recently updated its Right Size Parking Calculator, a map-based web tool that allows users to estimate parking use for multi-family development. First launched in 2017, the calculator uses context-sensitive, local data correlated to the building and its occupants, such as average unit square footage, percent of affordable units, average rent, and parking price per month. The tool also takes into account transit, population, and job concentrations in the surrounding area. The tool is intended to support and guide parking supply and management decisions by enabling informed discussions to take place.

Even as they deal with current challenges and opportunities, communities must consider the potential impacts of the anticipated arrival of autonomous vehicles. A 2017 Regional Plan Association (RPA) study suggests that in the New York City metro area, ride-hailing and autonomous vehicles could free up as much as 1 million square feet of parking space for TOD development over the next 20 to 30 years.

The RPA’s estimate is built on numerous assumptions, and no one knows for sure how quickly autonomous vehicles will arrive on the streets. A 2016 projection by McKinsey & Company predicts that anywhere from zero to 15 percent of new cars will be fully autonomous by 2030, depending on regulatory, technical, and consumer acceptance issues. Some car manufacturers have been much more optimistic. But even as TOD communities deal with present-day parking challenges, they should keep an eye to the future. In recent years, many parking structures around the country have been converted into other uses. Rewriting zoning and building codes to require parking structure adaptability is another way communities can prepare for the changes to come.

Want to read more?

Goldsmith, Robert. April 2017. Developing Parking Facilities in the Modern Day: Preparing for the Future.

Rodriguez, Michael. July 2018. Right-Sized Parking: Parking Ratios Down in D.C. Region.